Dr. Pepe’s Diploma Casebook: Case 63 – SOLVED!

Dear Friends,

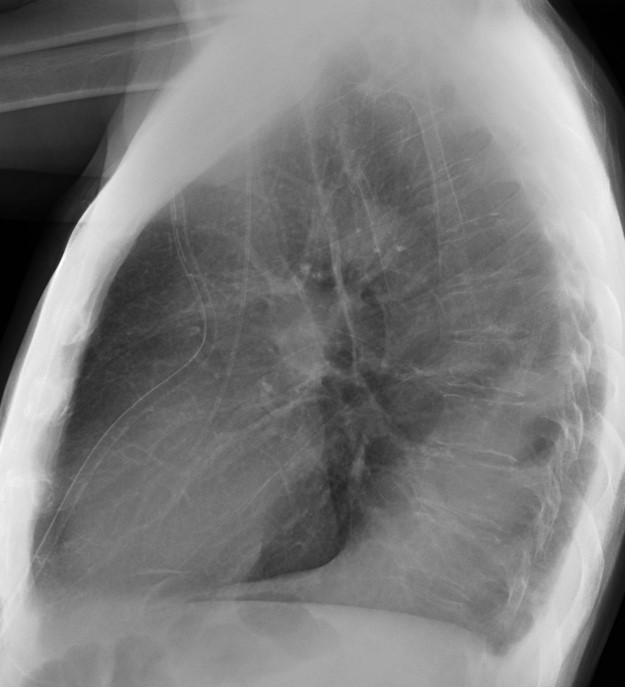

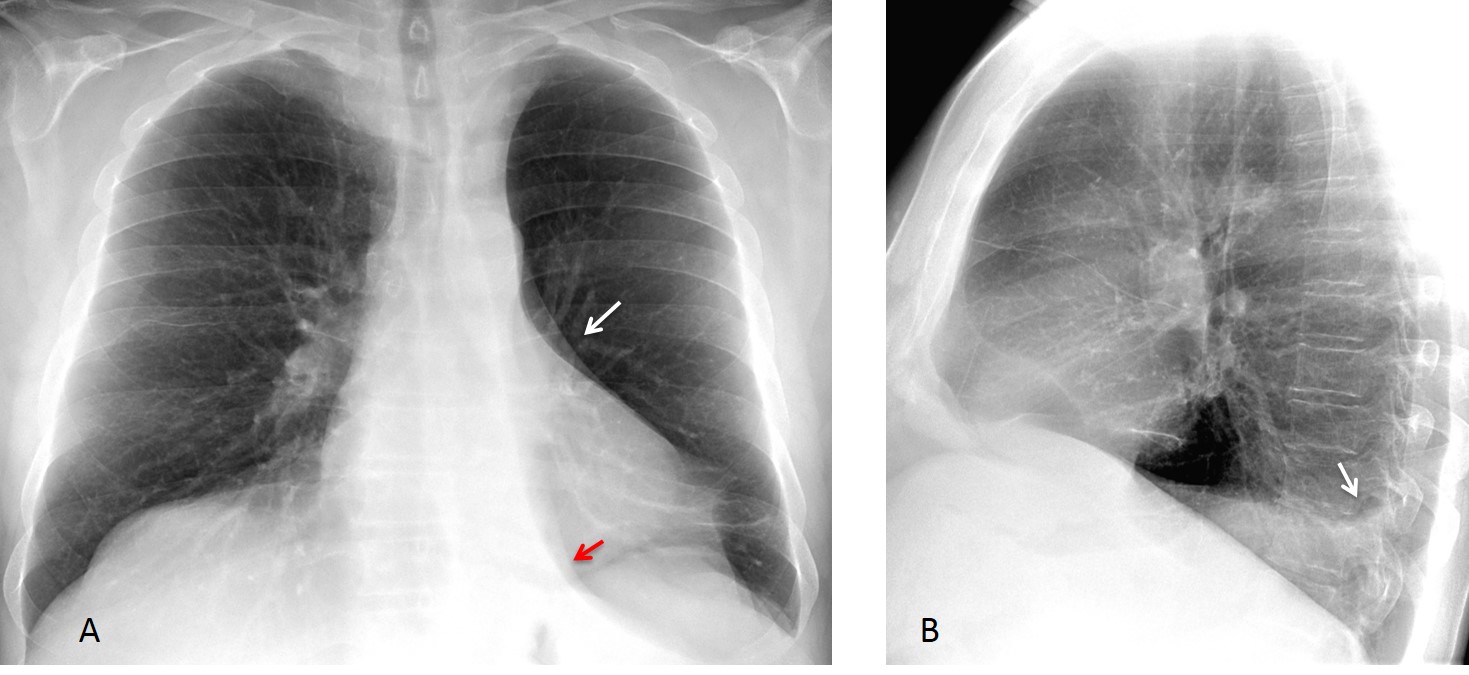

Today I am presenting the case of a 43-year-old man with lymphoma, admitted with fever and left pleural effusion. Radiographs were taken after pleural fluid drainage. Check the images below, leave me your diagnosis in the comments section and come back on Friday for the answer.

Diagnosis:

1. Pneumonia

2. LLL collapse

3. Pleural fluid

4. None of the above

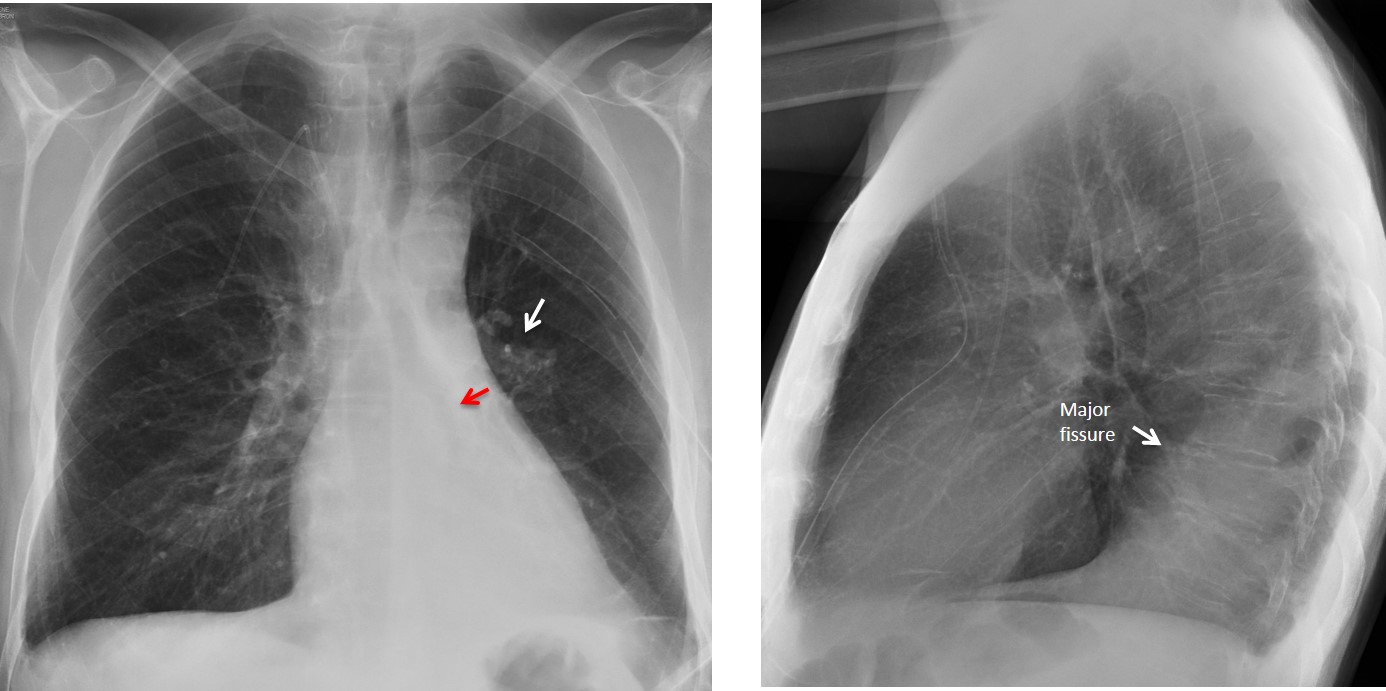

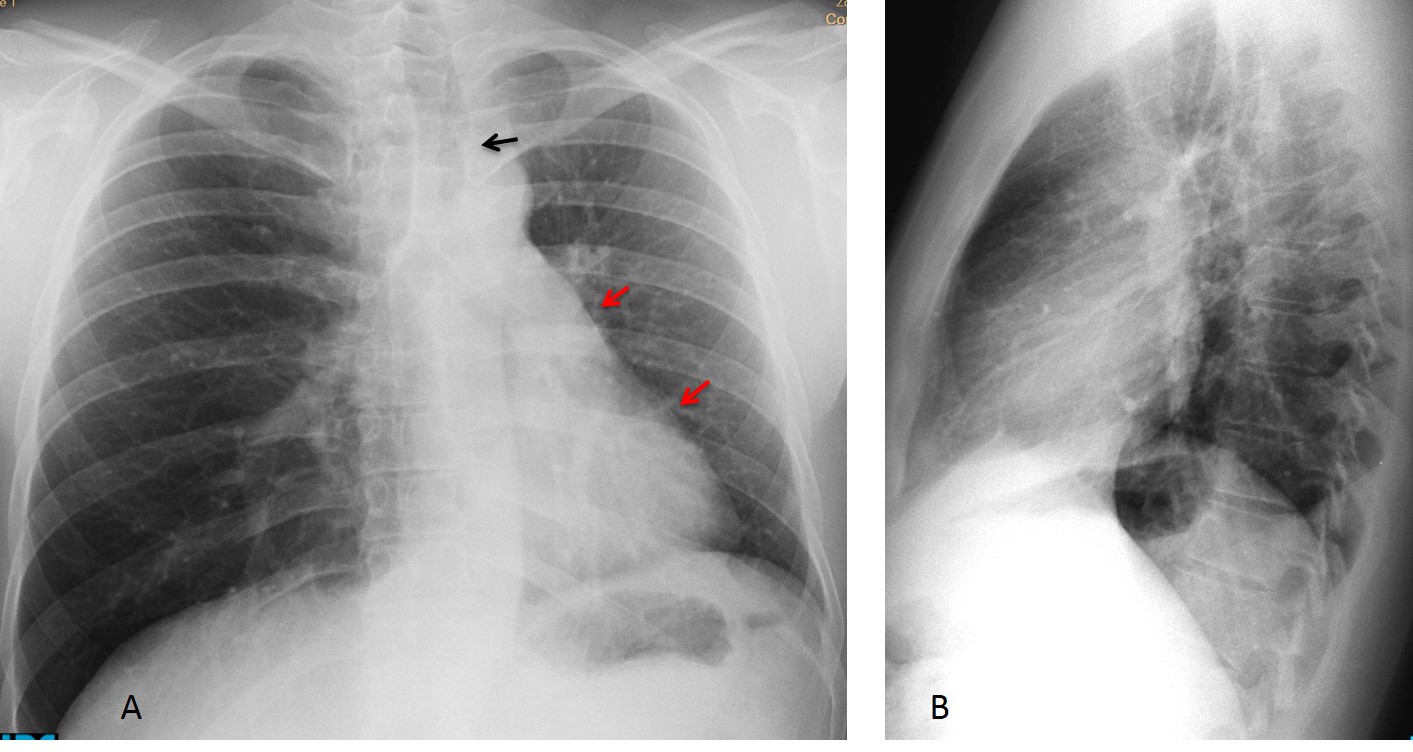

Findings: PA chest film shows increased density behind the cardiac silhouette. There is tracheal displacement and verticalisation of the LLL bronchus (red arrow) going into the opacity. There is downward displacement of the left hilum (white arrow), which is hidden behind the cardiac shadow. Lateral view shows a posterior triangular-shaped opacity, delimited by the major fissure. The radiographic appearance is typical of LLL collapse.

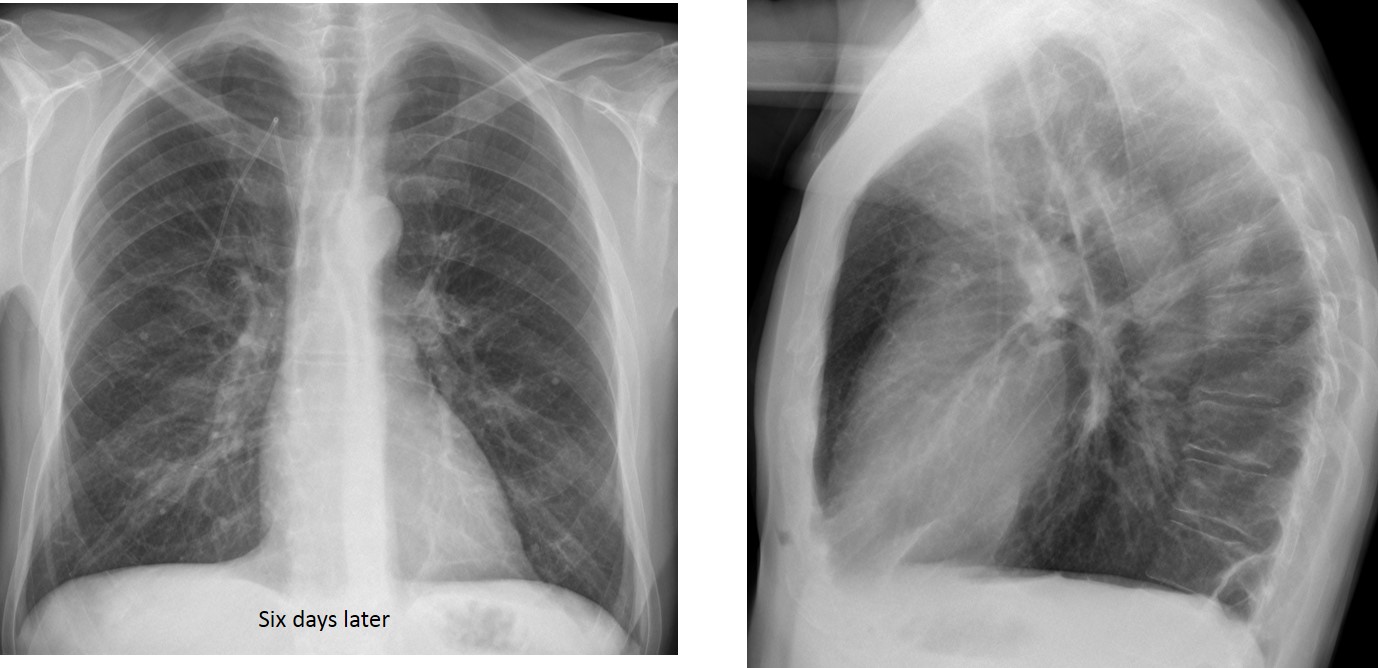

Bronchoscopy discovered a mucus plug obstructing the LLL bronchus. Six days later, after removal of the plug, the opacity has disappeared and the left hilum has returned to its normal location.

Final diagnosis: LLL collapse secondary to mucus plug.

This case is presented to discuss LLL collapse, which is important for two reasons:

1. The condition may go unrecognized because the lobe collapses behind the heart, delaying the diagnosis

2. A prompt diagnosis may be important, as malignancy is one of the main causes of LLL collapse.

In this presentation I would like to review common and uncommon manifestations of LLL collapse, with particular attention to findings that raise suspicion for this condition and prompt a diagnostic CT examination.

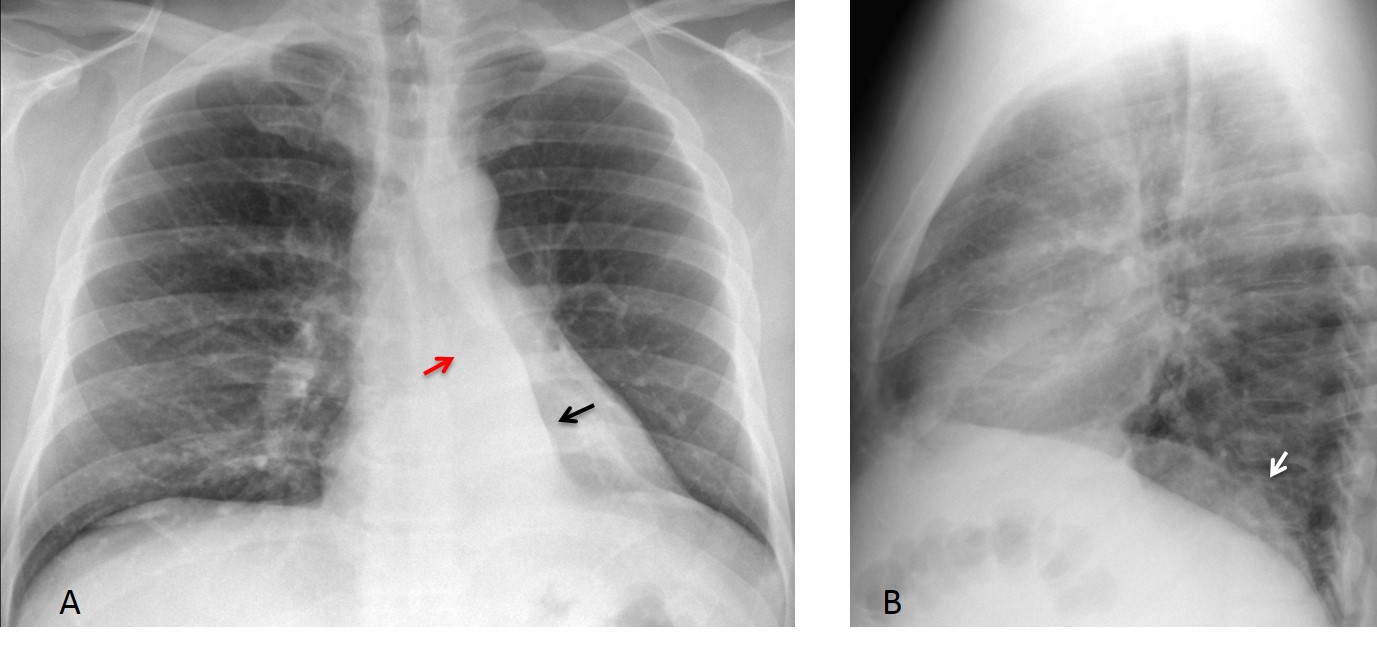

When LLL collapses, it retracts medially and hides behind the cardiac silhouette. Typical cases show the lobe as a triangular opacity behind the cardiac shadow in the PA view (Fig. 1 A). There is verticalisation of the left bronchus, which goes inside the collapsed lobe, ruling out pleural or mediastinal disease.

In the lateral view, depending on the degree of collapse, the lobe may appear as a faint opacity, with blurring of the left hemidiaphragm (Fig. 1 B) or as a posterior triangular shadow, with a range of possibilities in between (Fig. 2 B)

Fig. 1. Typical triangular opacity in LLL collapse (A, black arrow). Note the verticalized LLL bronchus leading into the triangular opacity (A, red arrow), a further sign of LLL collapse. The lateral view shows slightly increased opacity of the lower lung, with blurring of the left hemidiaphragm (B, arrow).

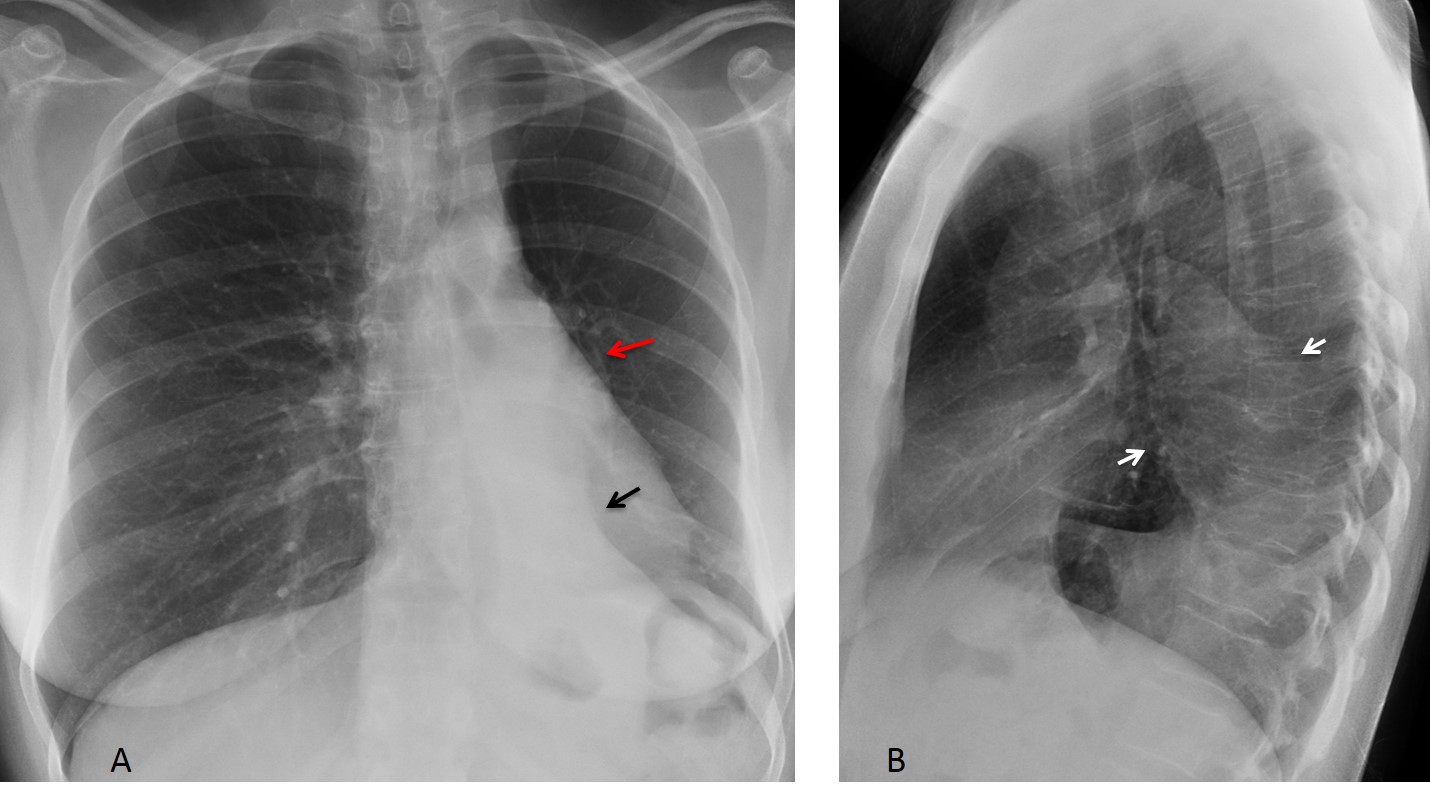

Fig. 2. Typical LLL collapse with triangular opacity behind the heart (A, black arrow). The hilum is descended and hidden behind the heart (A, red arrow). The trachea has shifted to the left. The lateral view shows elevation of the left hemidiaphragm and the posterior collapsed lobe (B, arrows).

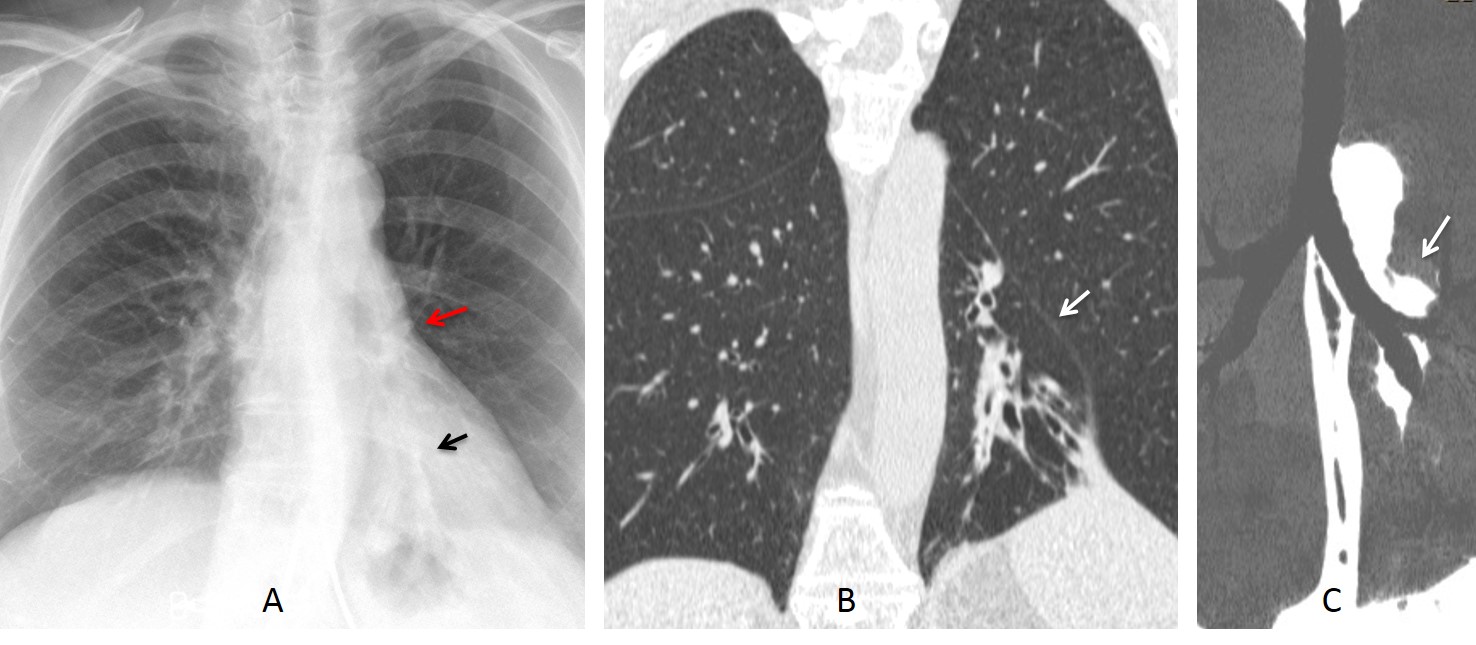

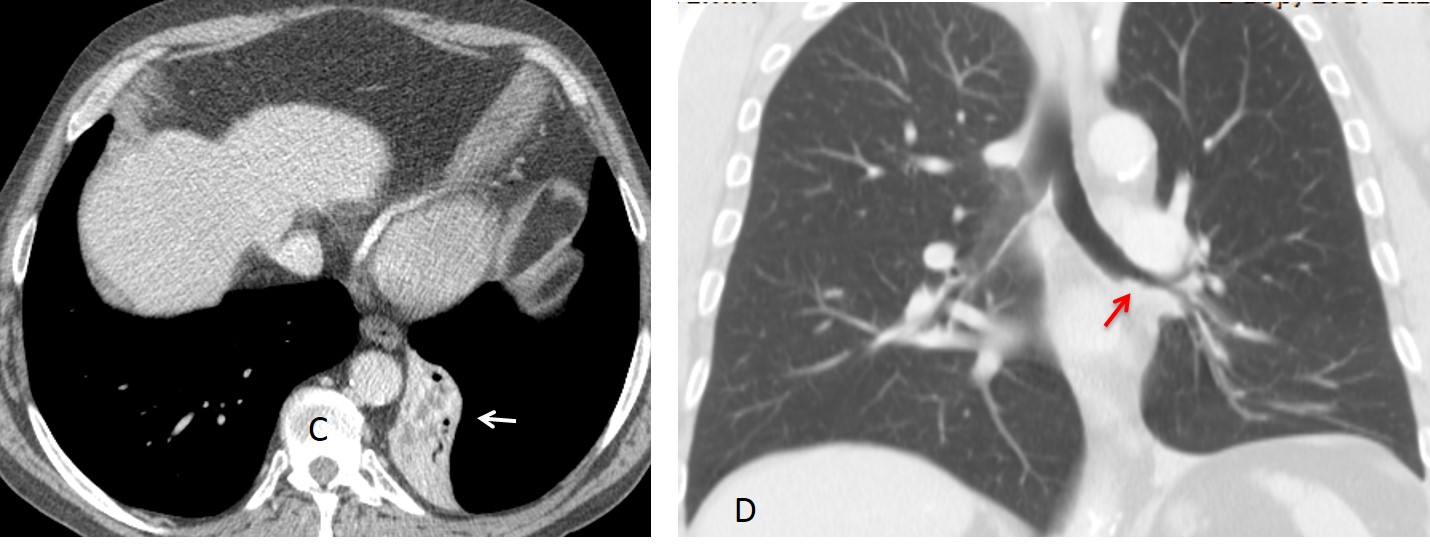

Aside from the triangular opacity in the PA and lateral views, certain secondary signs are very helpful in suspecting the diagnosis, especially when the collapsed lobe is not obvious. The most important one is downward displacement of the left hilum, which hides behind the cardiac shadow and simulates a small hilum (hidden hilum sign) (Fig. 3). This finding is almost always present.

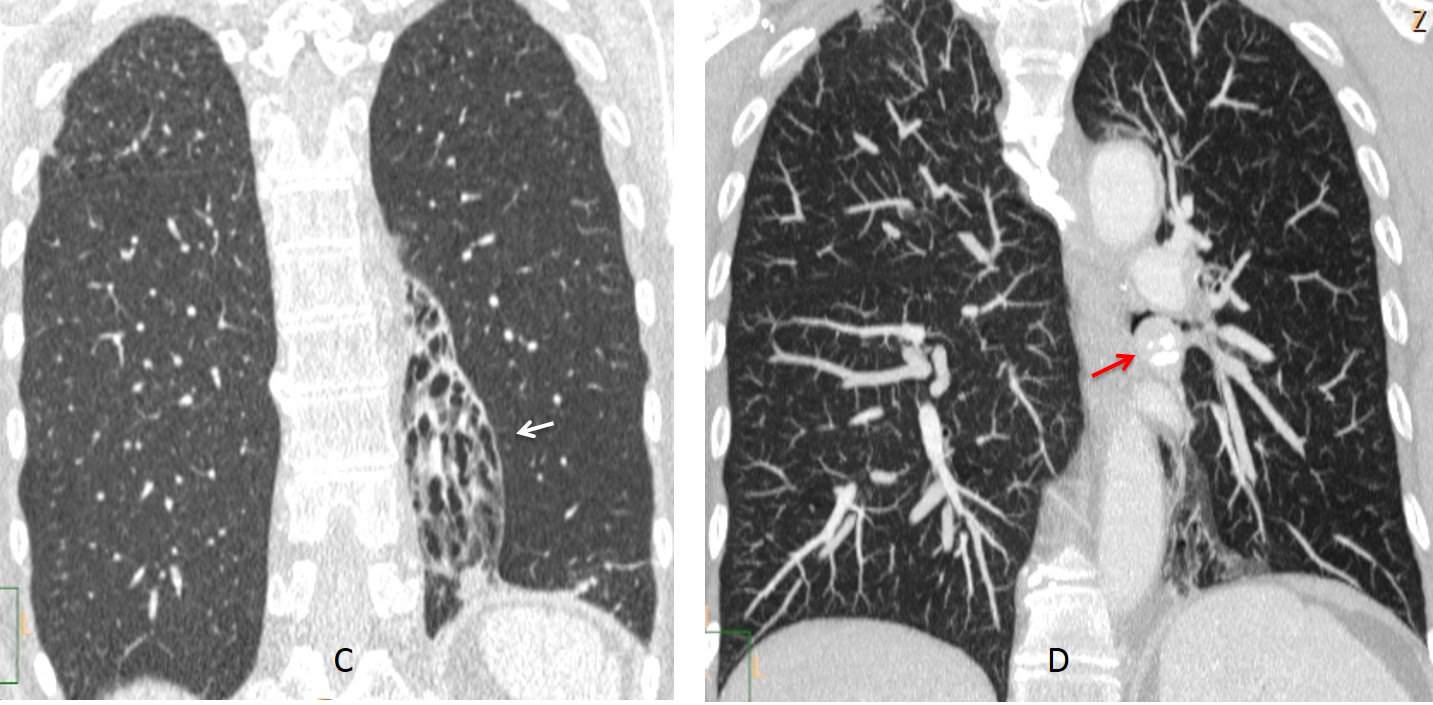

Fig. 3. LLL collapse secondary to bronchiectasis. Note the retrocardiac opacity (A, black arrow) and the descended left hilum (A, red arrow). Coronal CT confirms the volume loss and dilated bronchi (B, arrow). MIP reconstruction shows downward displacement of the hilum (C, arrow) and absence of endobronchial lesions.

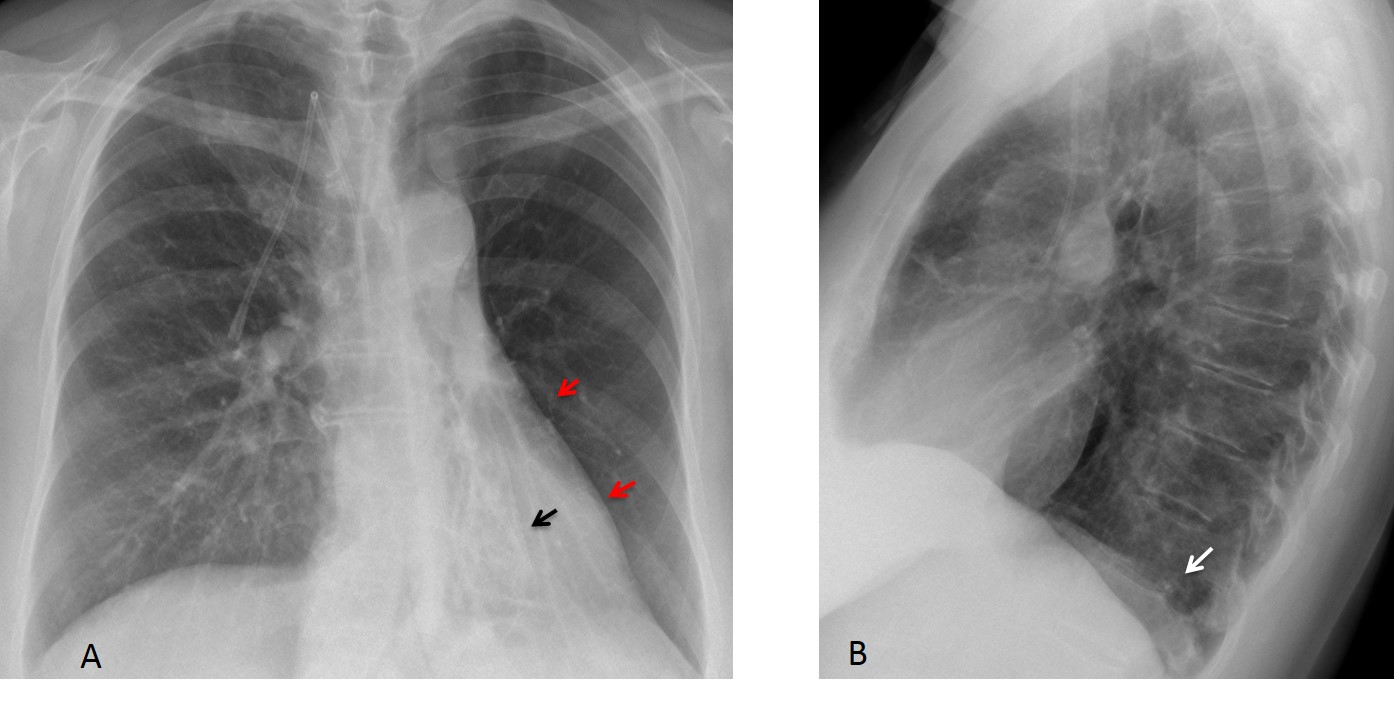

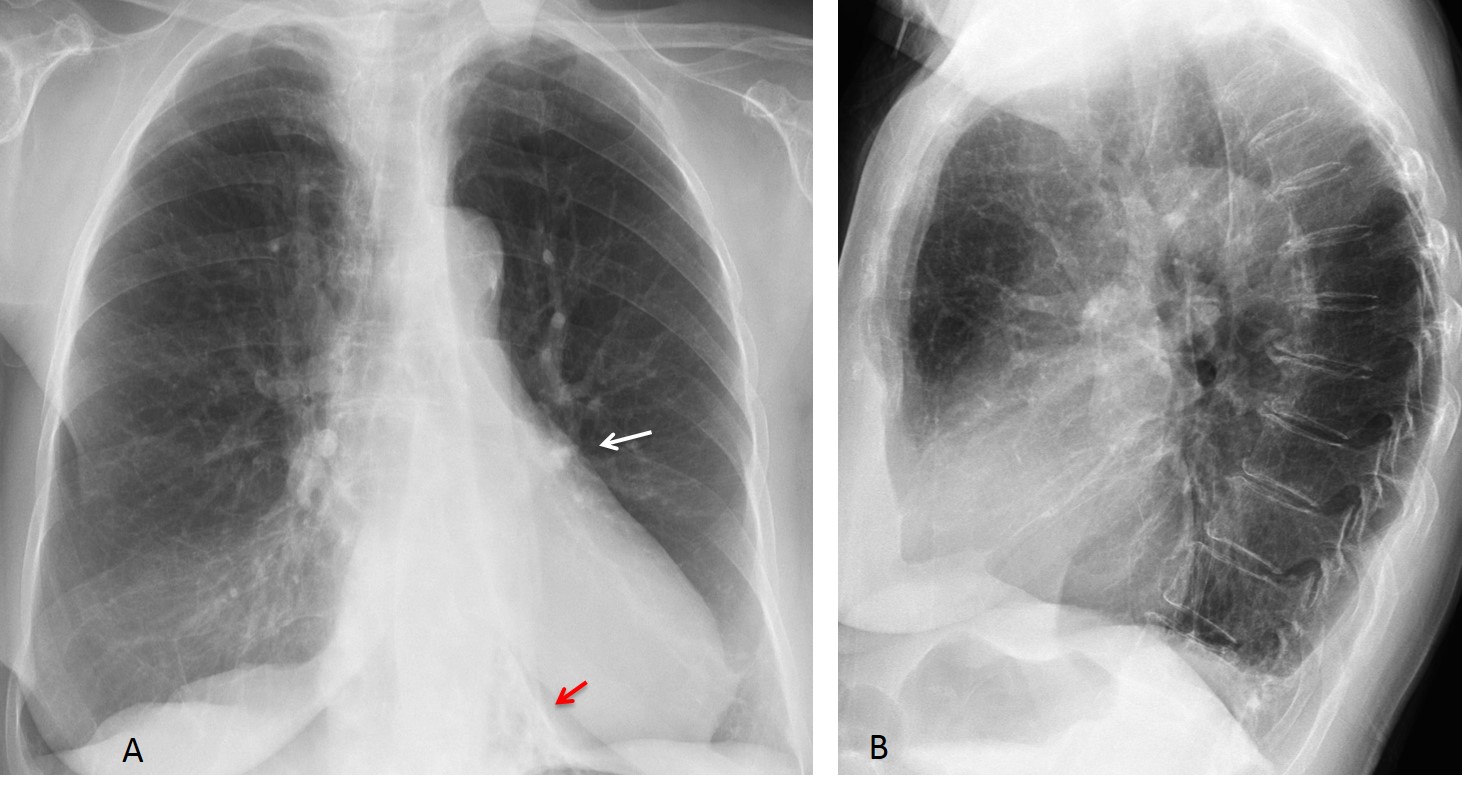

When the LLL collapses, it pulls on the heart, making it rotate clockwise. This causes a change in the normal heart contour, which becomes straighter (straight heart border sign – Figs. 4 and 5. See also the initial case, before and after). This sign is useful when the collapse is not obvious. The rotated heart also contributes to hide the descended hilum. Another sign is increased lung lucency, secondary to compensatory expansion of the LUL.

Fig. 4. Bronchiectasis and LLL collapse (A, arrow). The heart is rotated (A, red arrows). Note the hidden low hilum and increased lucency of the left lung. The lateral view shows only slight blurring of the left hemidiaphragm (B, arrow).

Coronal CT confirms the bronchial dilatation and LLL volume loss (C, arrow). A ventral slice shows a calcified endobronchial mass as the cause of the collapse and bronchiectasis (D, arrow). Final diagnosis: endobronchial carcinoid tumour.

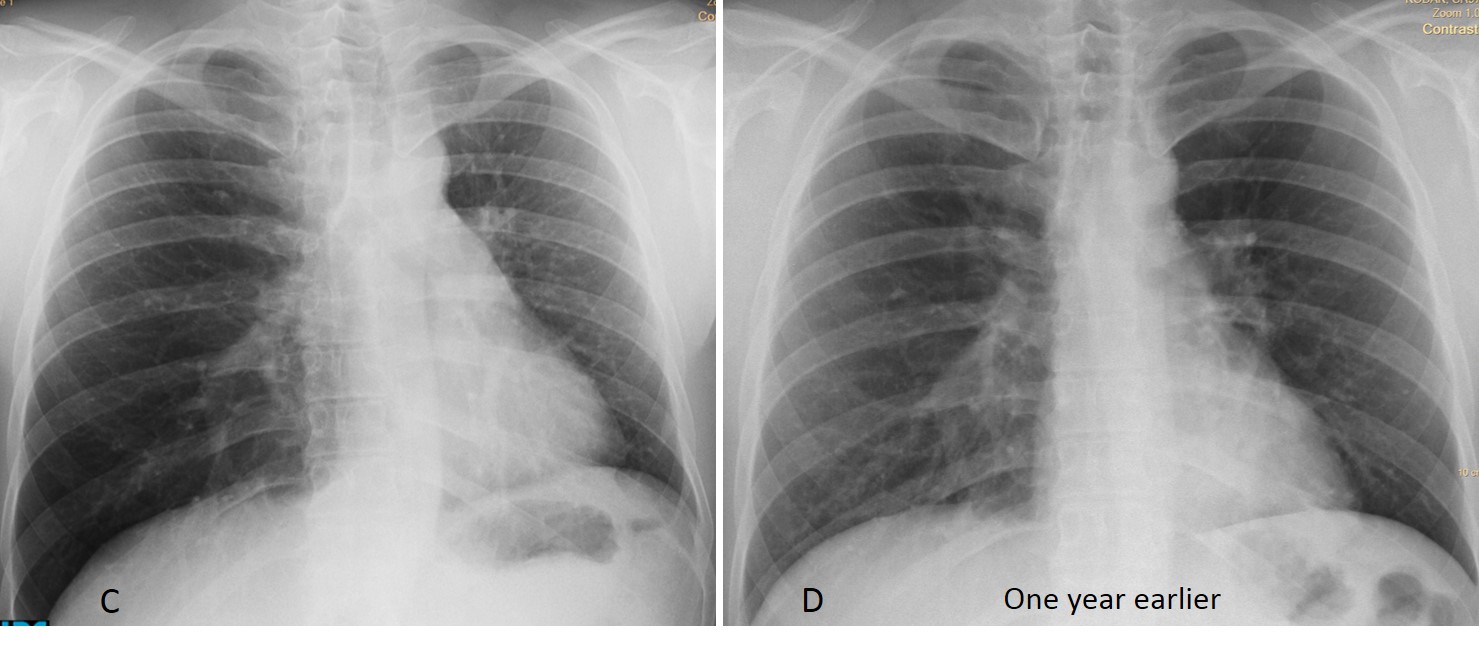

Fig. 5. Rotated heart as the initial sign of collapse. PA radiograph shows left tracheal displacement (A, black arrow). The heart is rotated towards the left, producing a straight left contour (straight border sign – A, red arrows). Aside from elevation of the left hemidiaphragm, the lateral view (B) is unremarkable.

The rotation of the heart is more evident when compared with a previous film taken one year earlier (D).

The findings were overlooked. A PA radiograph taken one month later shows progression of the LLL collapse, which is now obvious (E, arrow). Coronal CT confirmed the presence of a mass in the left bronchus (F, arrow). Bronchoscopy and surgery identified an endobronchial carcinoid tumour as the cause of the collapse.

In extreme LLL collapse, the increased lucency of the expanded LUL predominates and may be misleading. Identifying the descended hilum is the clue to suspecting the correct diagnosis (Figs. 6 and 7).

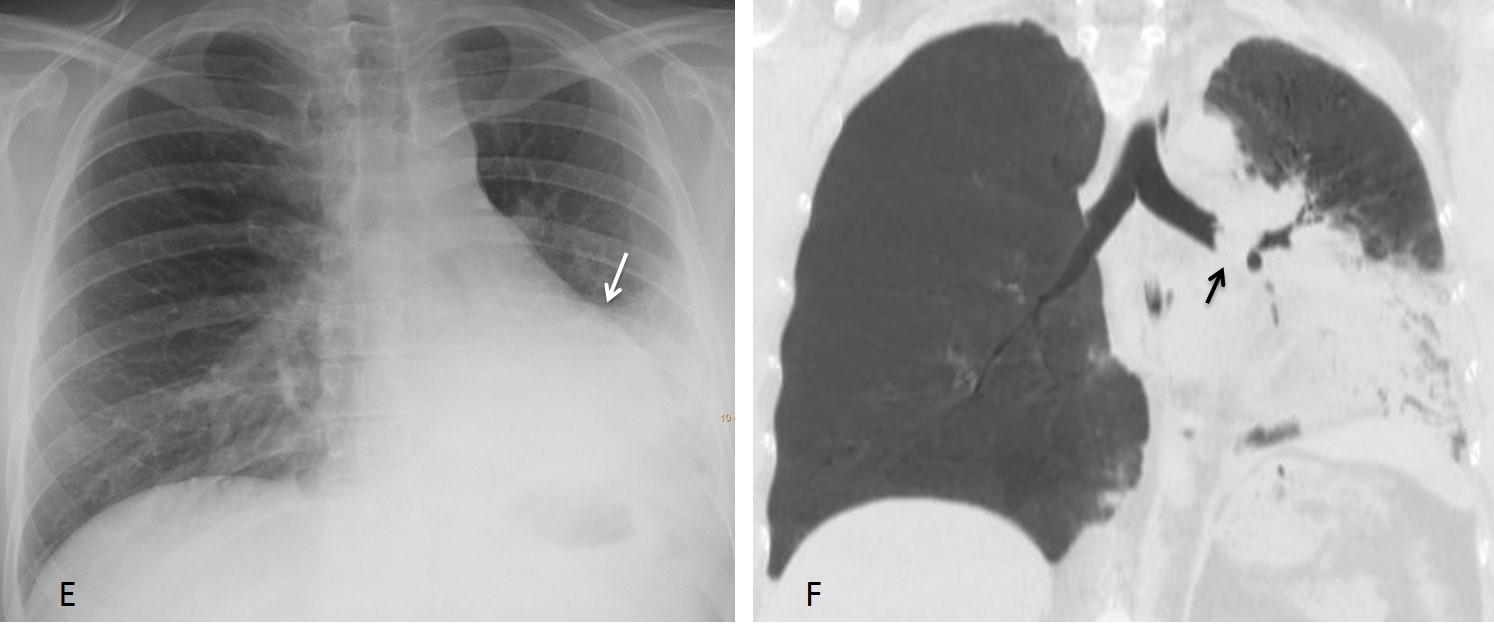

Fig. 6. Pre-op film for cataracts in a 72-year-old man. PA chest film shows a markedly lucent left lung. There is pronounced downward hilar displacement (A, white arrow) and a triangular-shaped paramediastinal opacity (red arrow). The posterior costophrenic angle shows minimal blunting in the lateral view (B, arrow).

Enhanced axial CT shows the markedly collapsed lobe (C, arrow). Coronal CT depicts a mass obstructing the LLL bronchus (D, arrow). Final diagnosis: carcinoma.

Fig. 7. Asymptomatic 78-year-old woman with marked LLL collapse secondary to bronchiectasis. Note the left lung hyperlucency, descended hilum (A, white arrow), and small triangular opacity of the collapsed lobe (A, red arrow). The lateral view is unhelpful.

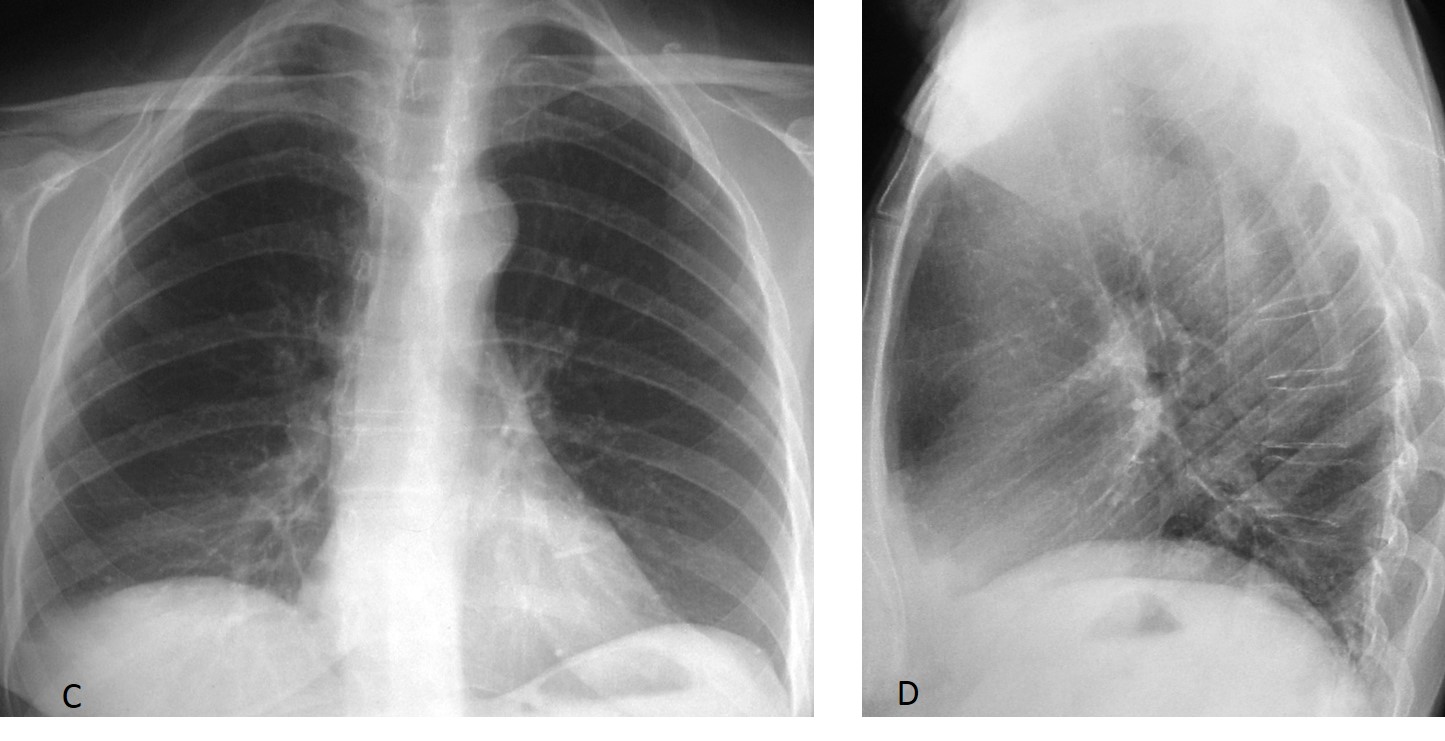

Occasionally, the tail of the collapsed LLL obscures the costophrenic angle in the PA and lateral views, simulating a small pleural effusion (Fig. 8. See also lateral views in Figs. 6 and 7). Again, the downward displacement of the left hilum helps to suggest the correct diagnosis.

Fig. 8. 52-year-old man with transient LLL collapse secondary to mucus plug. Aside from the obvious signs of collapse (triangular opacity, lowered hilum and increased lucency of left lung), PA and lateral views show obliteration of the costophrenic sinus (A and B, arrows).

Chest radiographs after removal of the plug show a normal appearance of the chest (C and D). The costophrenic sinuses are symmetrical and the left one shows no evidence of fluid.

Follow Dr.Pepe’s Advice:

1. LLL collapse appears as a triangular opacity behind the cardiac shadow.

2. The most useful secondary sign is downward hilar displacement.

3. Other signs of LLL collapse are compensatory emphysema and rotated heart.

4. Occasionally, LLL collapse simulates a small pleural effusion.

5. The most common cause of LLL collapse is malignant disease.

Hi Dr. Pepe,

On the lateral view image an atelectatic consolidation is visible with Damoiseau line suggesting LLL collapse with pleural fluid (small amount of flud is also visible in the right pleura)

I think on the pa view I can see a slight miedastinal shift to the left.

Of course drainage and central catheter are also visible.

That’s my thought, we’ll see…

The opacity in the lower left pulmonary field seems to correspond indeed to a lung colaps (maybe not the entire LLL), and on the PA there is a poor visualisation of the L diaphragmatic silhouette. But looks more like atelectasis, not pneumonia (smaller volume of lung).

No donut sign though, so not an effect from mediastinal lymph node enlargment.

I’d maybe take a look on echography if I were on shift in the ER (just to check if of liquin nature). 🙂

2

Collapse,i think

i think is LLL collapse. we have lost of volume.

> i like to now if is the first pleural fluid drainage

> why the bullau is not posteriorly

> if the patient had pneumothorax after thoracentesis

2)

Increased density of retrocardiac lung, contour of descending aorta not visible,

Lateral view supporting these findings of LLL collapse.

iniziale atelettasia rotonda,da compressione ab-extrinseco del pregresso versamento pleurico.

inability to trace the normal left hemidiaphragm contour not only posteriorly and medialy due to LLL partial collapse but also in the anterior and lateral costodiaphragmatic recess

patient rotated to the left, probably slight inferior mediastinal shift to the right

pneumothorax

intrathoracic bowel herniation?

LLL collapse secondary to enterothorax, diaphragmatic herniation

Rib fracture, trauma?

I believe all of you are very smart…

4. Non of the above.

Left hemidiaphragm rupture.

Dilated oesophagus filled with air.

Bronchooesophageal fistula with air-filled esophagus, aspiration and atelectasis.

Lll collapsus