Dr. Pepe’s Diploma Casebook: Case 44 – SOLVED!

Dear Friends,

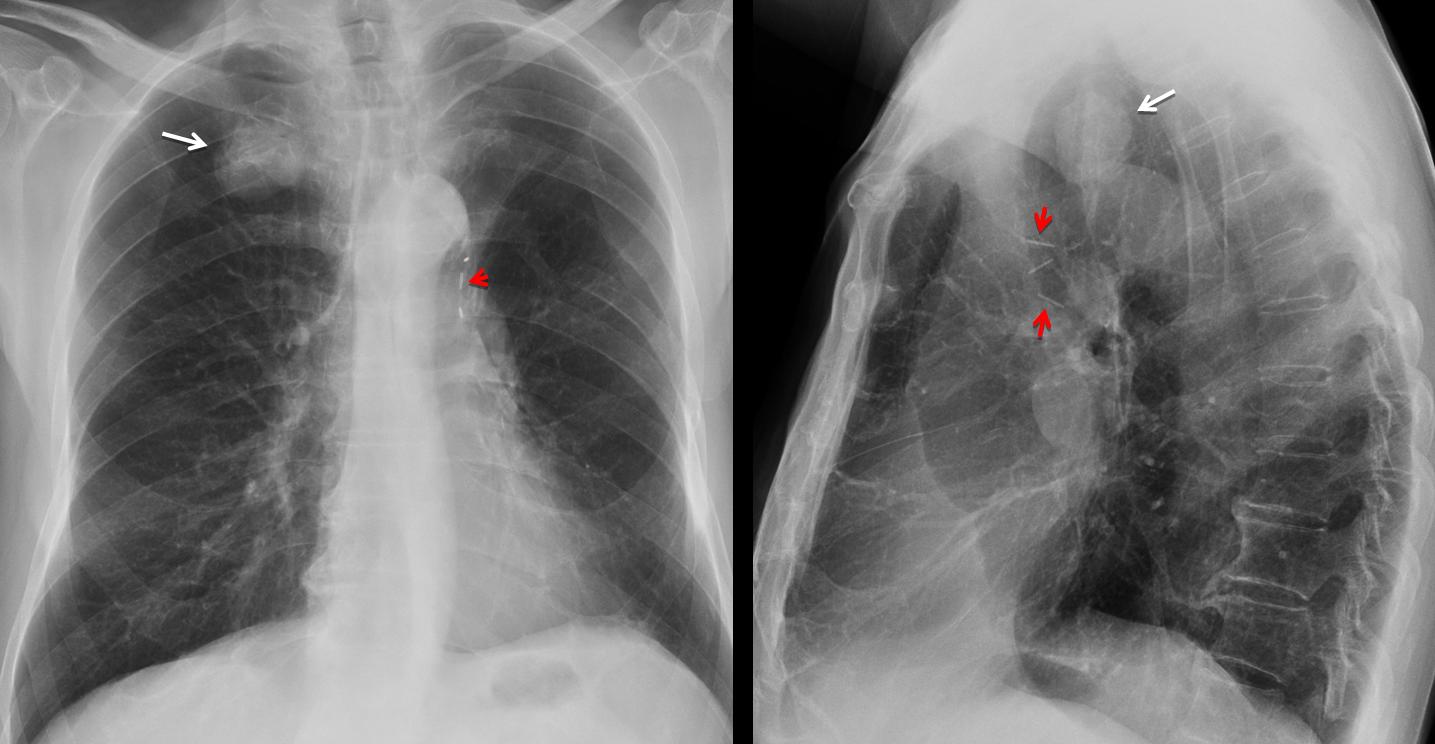

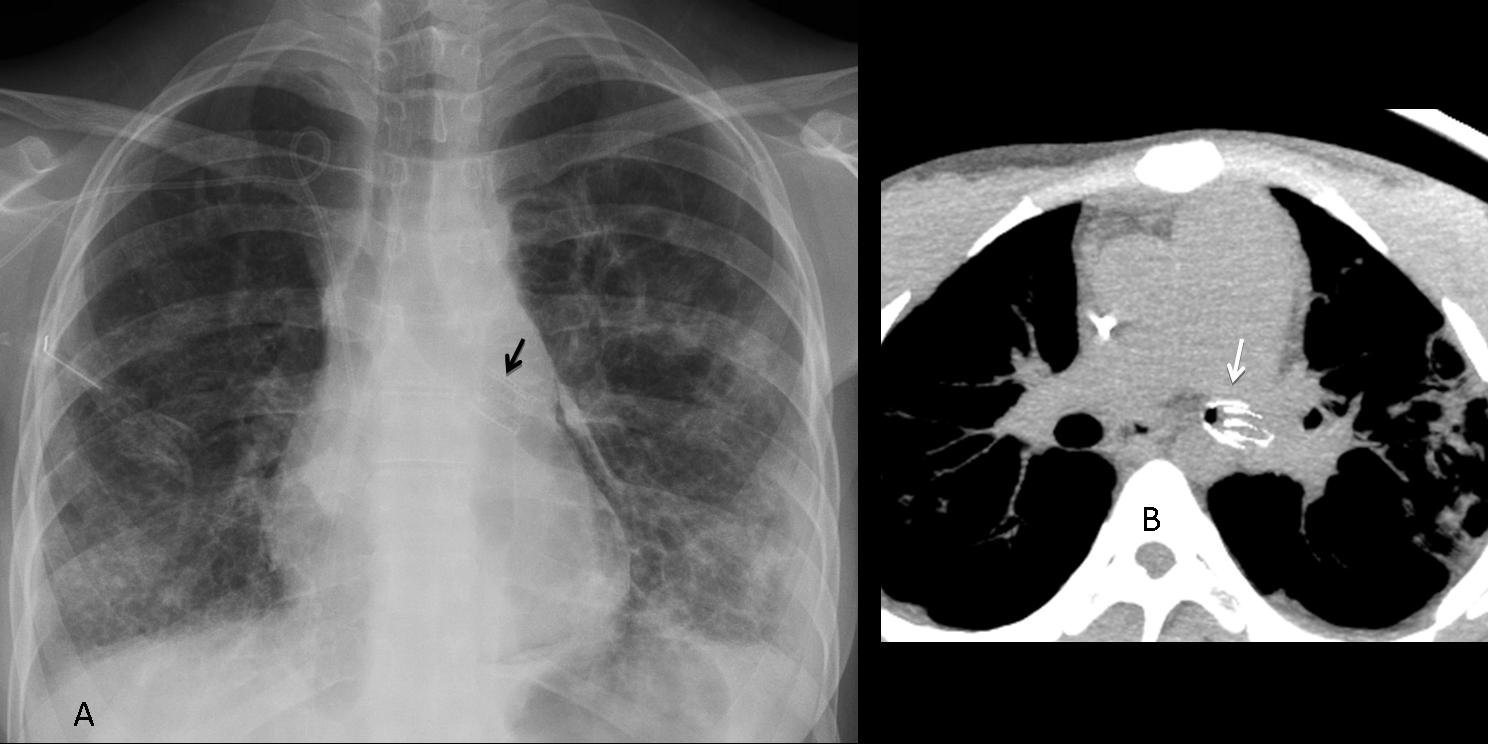

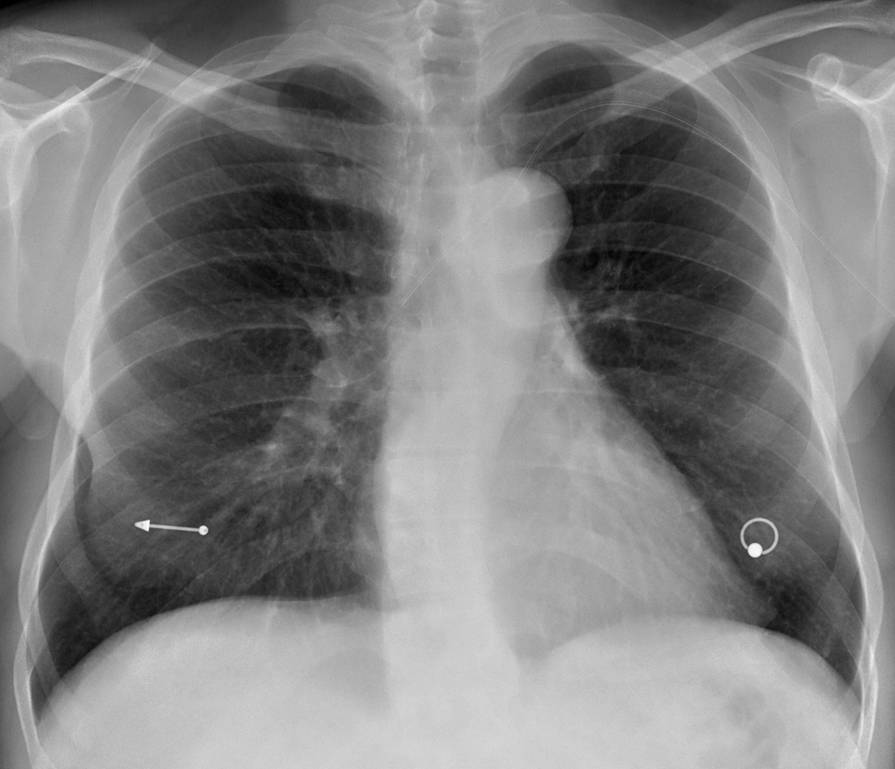

Presenting the case of a 45-year-old man with fever, one week after coronary surgery. I apologise for the poor quality of the PA radiograph, but it does not influence the diagnostic evaluation.

Check the images below and leave your opinion in the comments. The answer will be posted on Friday.

Diagnosis:

1. Pericardial fluid

2. Pleural fluid

3. Both

4. Anything else

Findings: Aside from obvious pleural fluid in the left costophrenic sinus, there is pericardial effusion, as evidenced by the thickened band between the epicardial and mediastinal fat in the lateral view (A, arrows). The most striking finding is a convoluted metallic opacity projected over the posterior heart (B, arrows). In a post-op patient, the first consideration should be a retained surgical sponge. CT confirms the pericardial effusion (C, white arrows) as well as the sponge within the pericardial space (C, red arrow).

Final diagnosis: retained surgical sponge in the pericardial cavity.

This case is presented to emphasise the importance of discovering metallic densities in the chest radiograph. Why are they important? Because their high density makes them easily recognisable, and because they do not exist in the body. Once identified, we can be certain they are foreign material and then determine how they got into the chest.

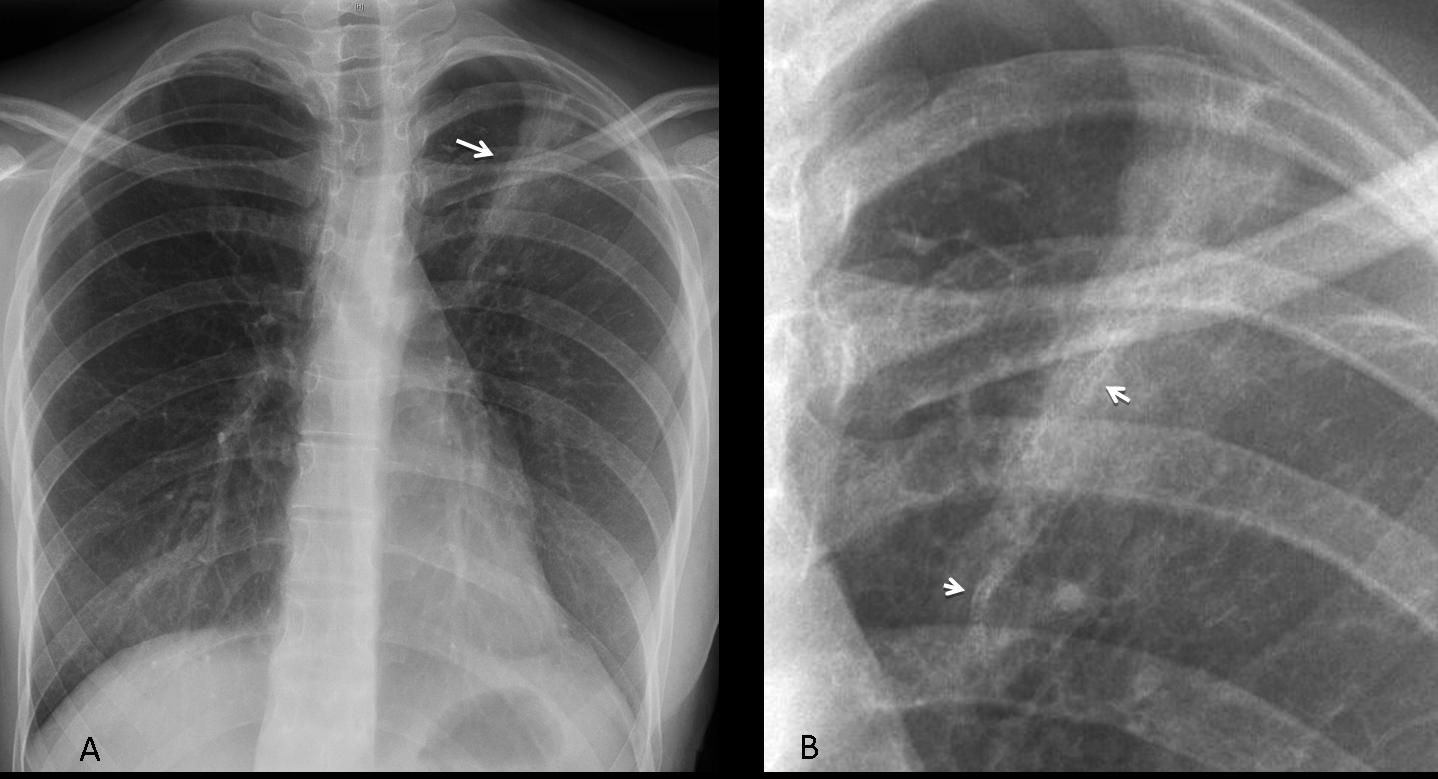

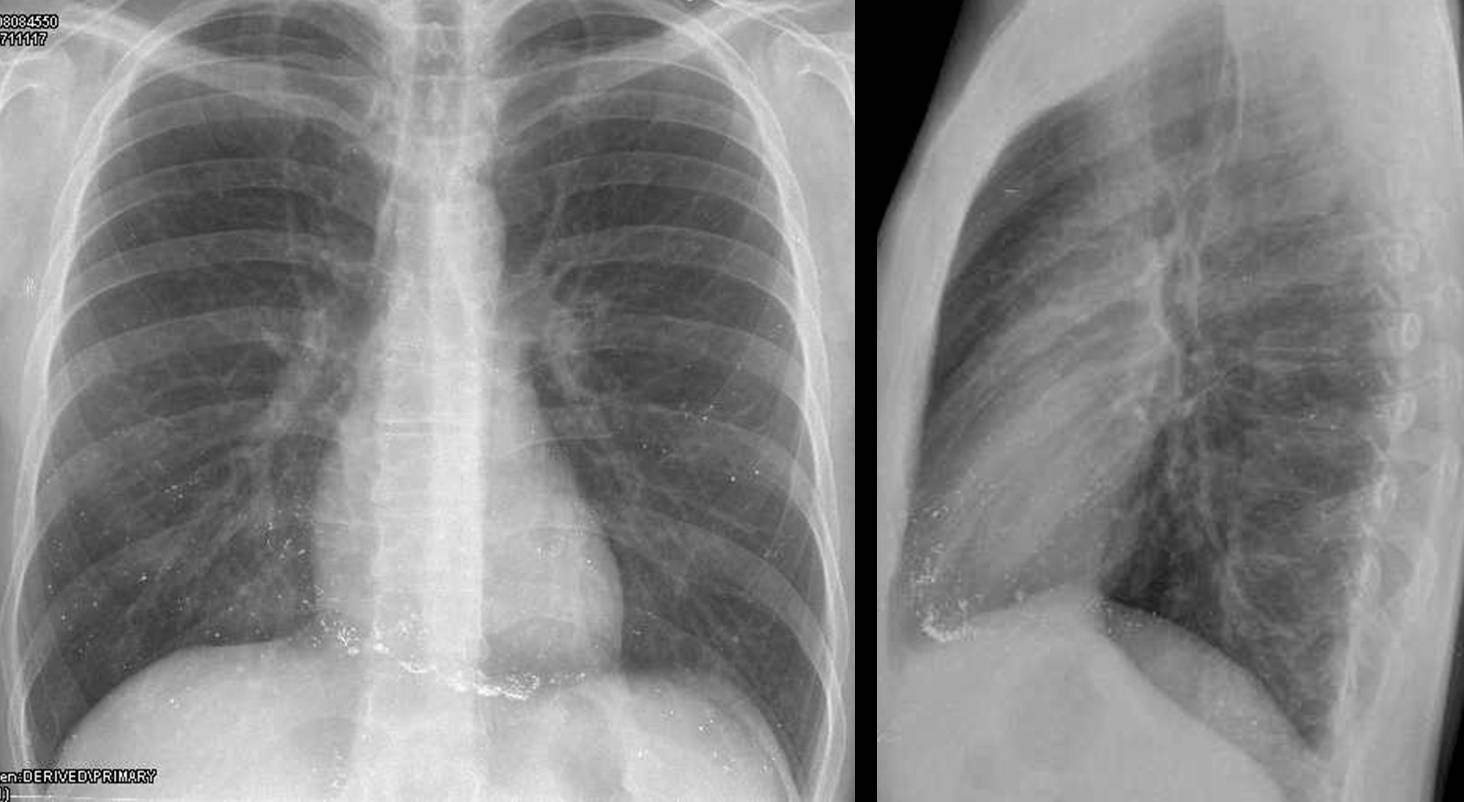

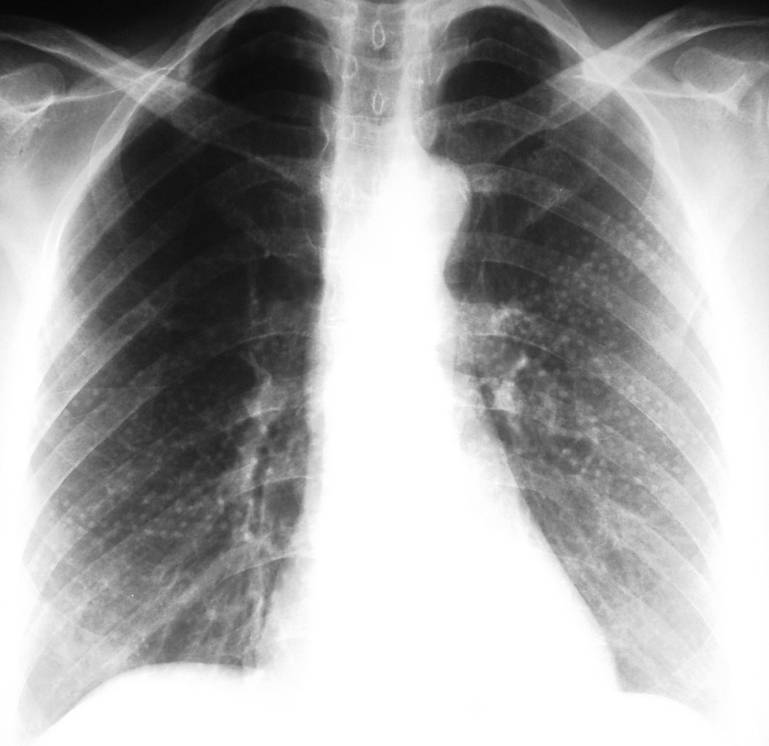

Metallic densities are usually secondary to a surgical procedure, and may be elements left in place unintentionally, as in the case presented. Excluding obvious medical devices such as pacemakers and prosthetic heart valves, the most common are surgical sutures. Recognising them indicates a previous operation. They can be of great help when clinical information is not available, as in the case below of a 65-year-old man with a nodule in the RUL (Fig. 2, white arrows). There are signs suggestive of LUL collapse, but the metallic sutures (Fig. 2, red arrows) and broken ribs point to a previous LUL lobectomy, which strongly suggests a second primary as the most likely etiology of the RUL nodule.

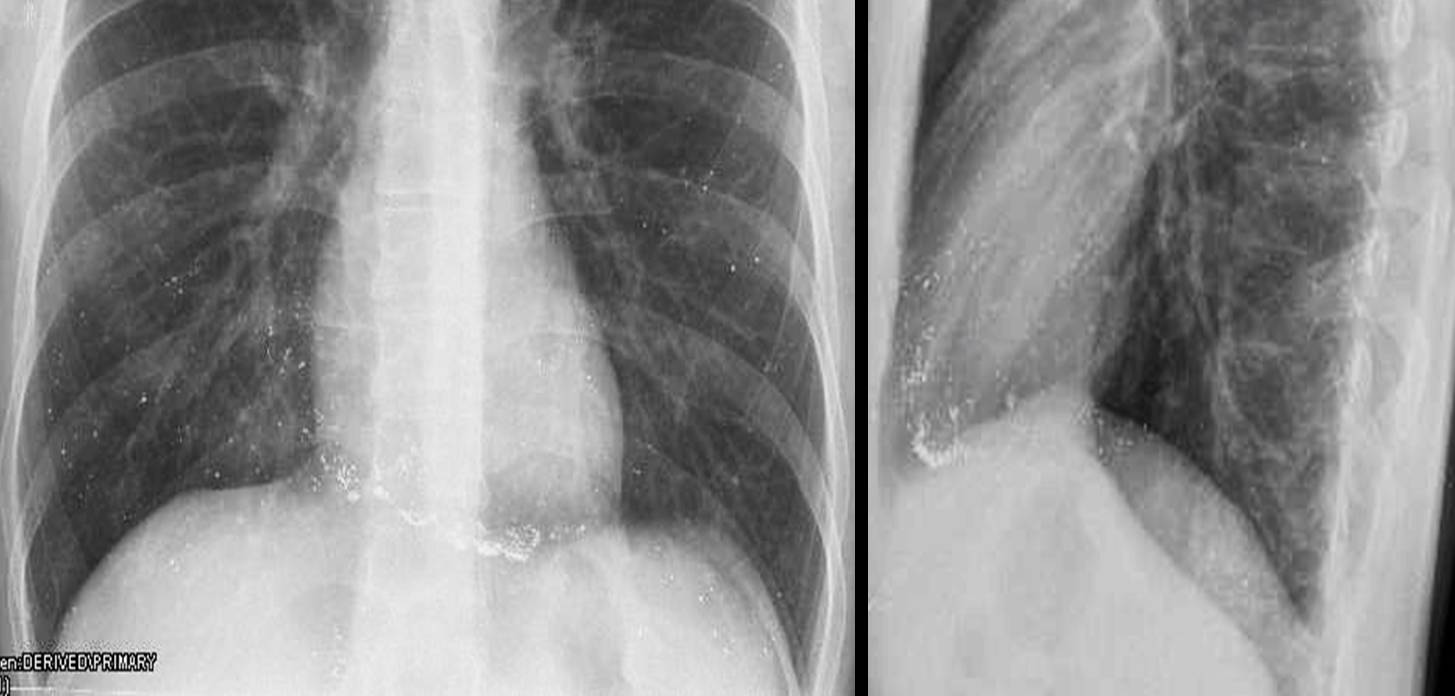

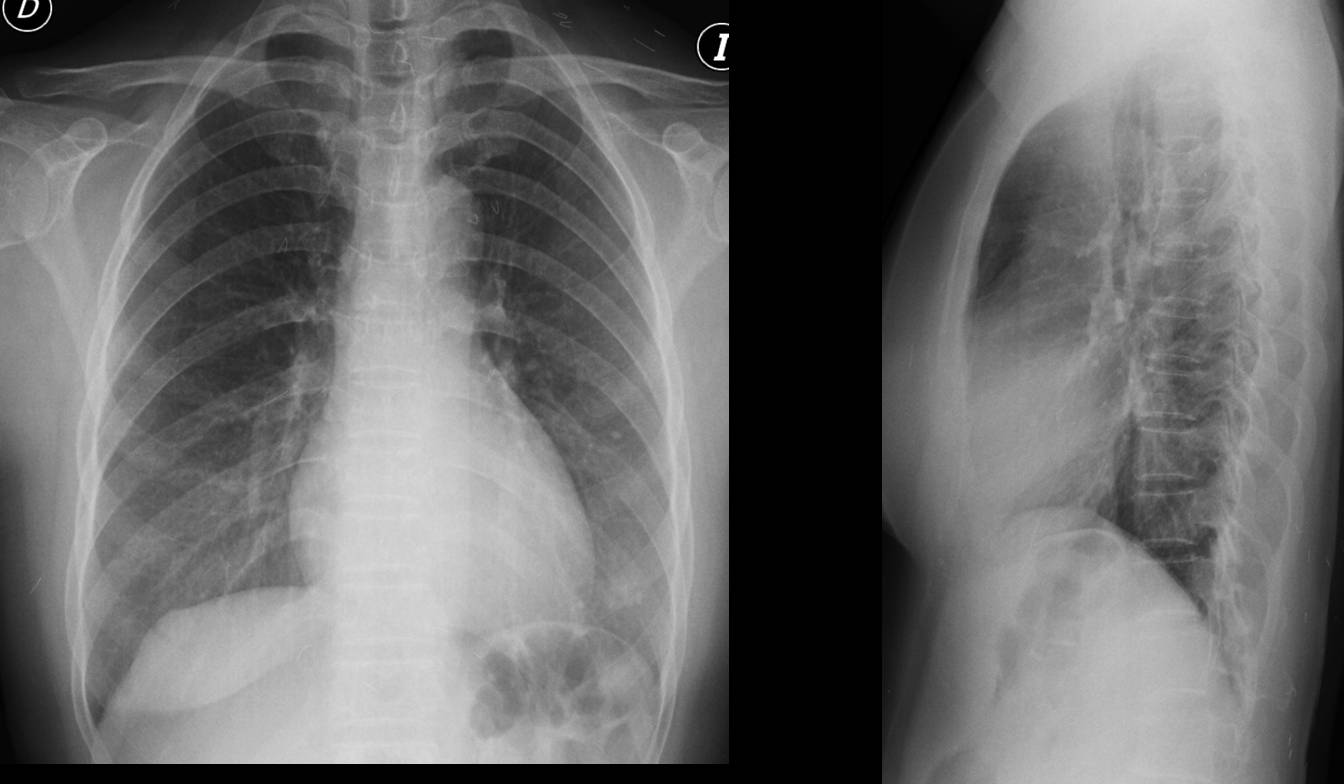

Pulmonary staples may be difficult to see due to their small size and because high Kv tends to ‘burn’ metallic density. Awareness of this fact will avoid diagnostic dilemmas as in the case below of a 23-year-old girl with a non-descript LUL infiltrate (Fig. 3a, arrow). The close-up view reveals multiple rounded staples within the infiltrate, pointing to a man-made opacity (Fig. 3b, arrows).

Diagnosis: changes after LUL bullectomy for recurrent pneumothorax.

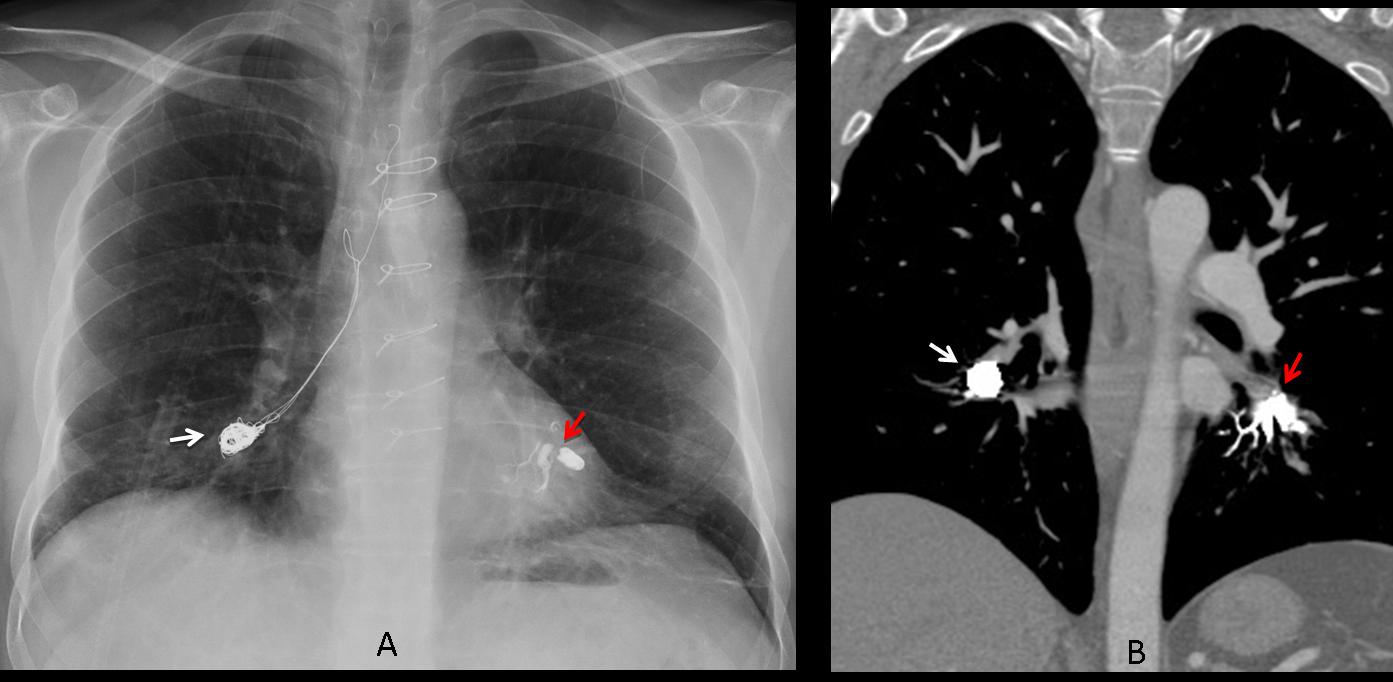

Not all postoperative metallic opacities are sutures. They may correspond to steel coils or acrylic glue used for embolisation of aneurysms or AV malformations. They are fairly dense and easily recognized (Fig. 4).

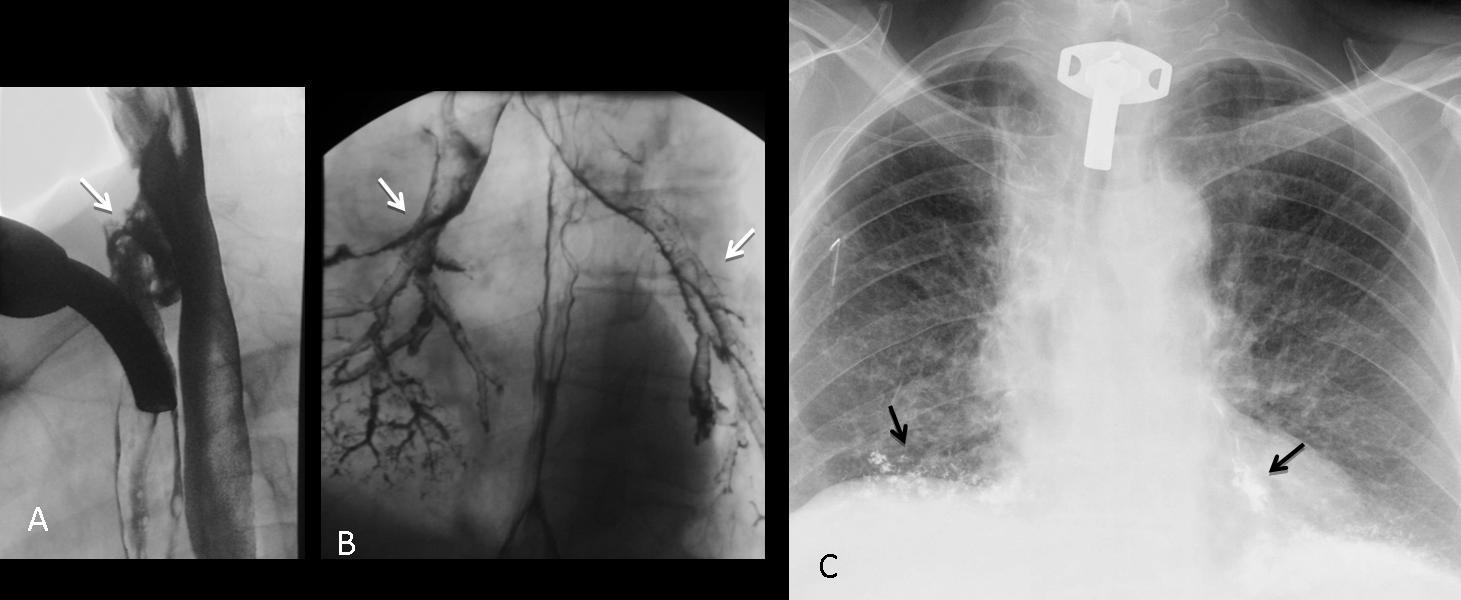

Fig. 4 (above): 47-year-old male with Hughes-Stovin syndrome and bleeding pulmonary artery aneurysms. The right lower pulmonary artery has been embolised with coils (A,B white arrows), whereas the left lower pulmonary artery has been occluded with n-butyl-cyanoacrylate (A,B red arrows).

Another metallic element is bronchial stent, used to relieve bronchial obstruction. These devices may be overlooked because their walls are thin and do not produce sufficient contrast in high KV films (Fig. 4).

Fig. 5 (above): 21-year-old woman who underwent bilateral pulmonary transplantation for cystic fibrosis. Stenosis of left main bronchus treated with a stent, barely visible in the chest radiograph (A, arrow) and better seen on axial CT (B, arrow).

Not all metallic densities are of surgical origin. The patient below has no history of previous surgery. What would your diagnosis be?

Radiographs show multiple metallic droplets in both lungs. They are more abundant in what at first glance seems to be the pericardium. Close examination demonstrates that the opacities are in the area of the right ventricle. This appearance is typical of mercury poisoning, usually injected in a peripheral vein with suicidal purposes. The injected mercury pools in the right ventricle, and from there it embolises the peripheral arteries.

A not uncommon cause of metallic embolisation to the lungs is a previous interventional procedure in another part of the body (vertebroplasty, AVM embolisation). The injected material may spill into the neighbouring veins and find its way into the bloodstream, ending as dense pulmonary emboli. Patients are usually asymptomatic, although deaths have been reported.

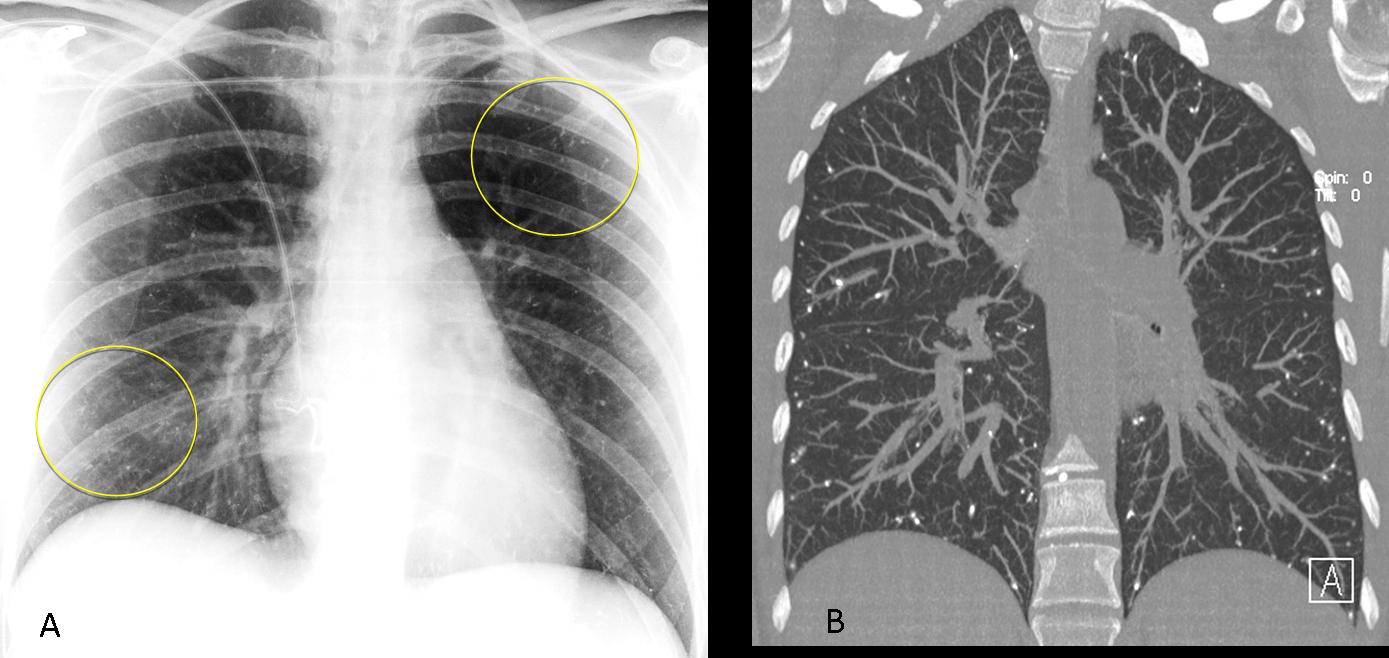

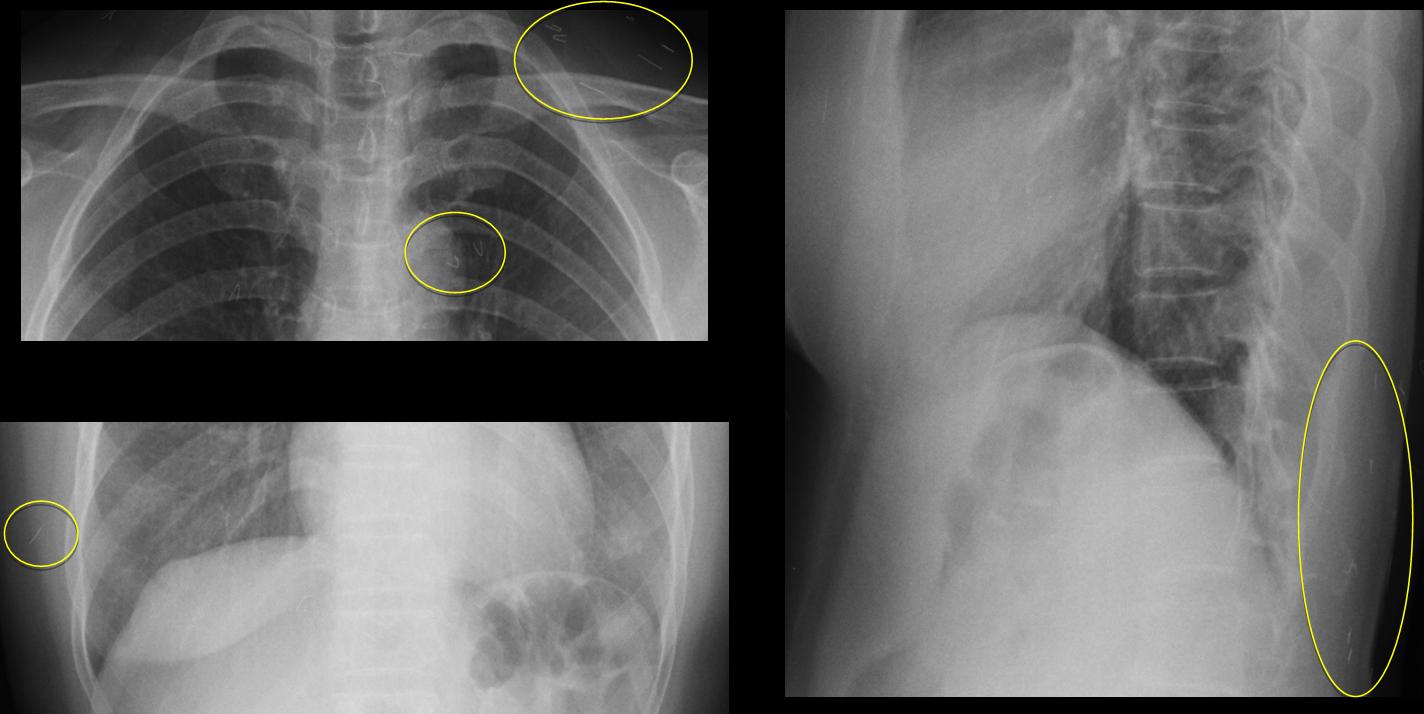

Fig. 8 (above): 42-year-old man after embolisation of a cerebral AVM with n-methyl-butacrylate. AP chest radiograph shows multiple peripheral metallic emboli (circled in A), confirmed with coronal CT (B). Case courtesy of Dr. Eva Castañer.

Most non-surgical metallic densities reach the lungs by aspiration through the bronchial tree. The most common is barium aspiration, either due to impaired swallowing or, less commonly, to a bronchoesophageal fistula related to malignancy in most cases. Barium usually goes to the right or both lower lungs.

Fig. 9 (above): 60-year-old male with oesophageal stenosis secondary to a suicide attempt with caustics. Barium swallow caused aspiration into the right lower lung. Stent in oesophagus.

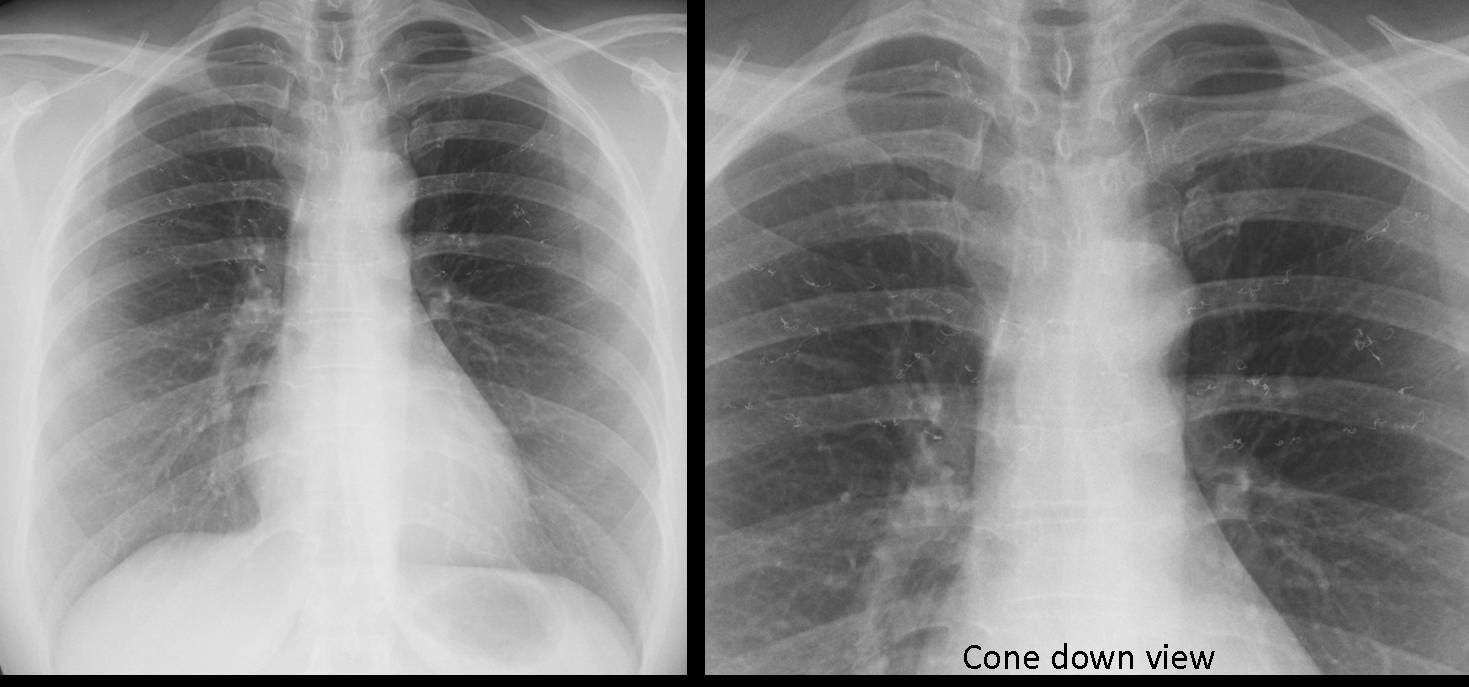

Fig. 10 (above): 64-year-old man with advanced carcinoma of the upper oesophagus. Barium swallow demonstrates a tracheoesophageal fistula (A, arrow), with passage of barium to both lower lobes (B, arrows). Chest radiograph shows the barium in both lower lobes (C, arrows).

Time to test your knowledge. Below are the preoperative radiographs of a 53-year-old woman.

What would your diagnosis be?

1. Filariasis

2. Cysticercosis

3. Metallic sutures

4. None of the above

There are several straight and bent metallic opacities in the soft tissues, some of them projected over the lung fields. The appearance is very typical of acupuncture needles. Some types of acupuncture involve permanent placement of the needles, which remain embedded in the soft tissues, as in the present case.

Another possible cause of metallic opacities in the skin are gold threads implanted in the subcutaneous tissue of the neck and cleavage. This is not an uncommon procedure in plastic surgery to correct sagging skin. This case (below) was shown in Caceres’ Corner and of 12 responses, only one was right.

Nowadays metal nipple piercing is common. You might think this to be a fad only among young people, but the patient below is a 56-year-old man. I have nothing against this practice, because piercings are excellent nipple markers!

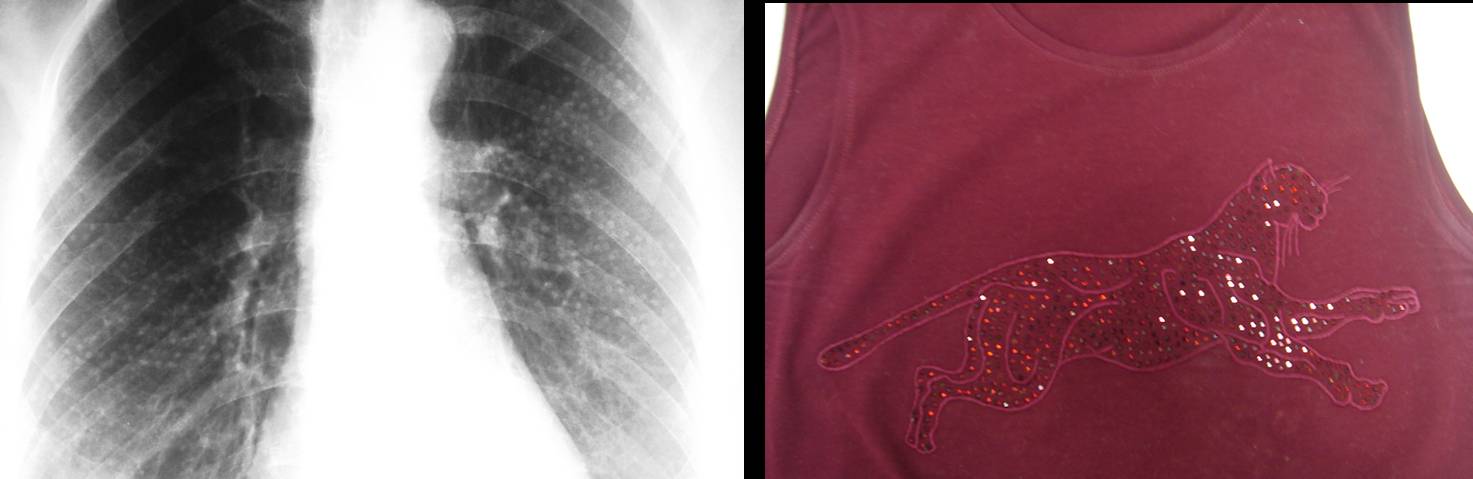

I have covered many of the possible causes of metallic opacities in the chest and would like to test you with a final case of a 28-year-old asymptomatic woman. What would you say?

1. Metallic aspiration

2. Mercury poisoning

3. Old chicken pox pneumonia

4. None of the above

This is the last and not uncommon cause: unremoved garments. The patient did not take off her blouse when the radiograph was taken.

Follow Dr. Pepe’s advice:

- Metallic density opacities are easily recognised and are always foreign material

- The most common are secondary to surgical procedures

- Barium aspiration is the next most common cause

- Always rule out foreign material in the skin or garments

atelettasia rotonda.

Sindrome post-perfusionale, dovuta alla reazione fisiopatologica delle alterazioni micro-circolatorie e parafisiologiche della CEC(circolazione extra-corporea),con accumulo interstiziale ed imbibizione di un lobo-segmento polmonare.

Pleural fluid

Dressler’ syndrome

round atelectasis..

I think both of them

fat pad sing on the lateral view (pericardial effusion)

and pleural effusion on the right base.

there is also material crirurgical on the posterior space on the lateral view. i cant see it on the frontal view.

I think there is left side free as well as subpulmonic effusion

both

pleural fluid on the left side, infected retained hemothorax, empyema post op.

I think 3,

Dressler syndrom

🙂 oops someone forgot a little bit wire in the heart.

could be a sternal wire ruption after surgery….;)

Good, you are getting there! Keep thinking

It is either a LLL pneumonia or a LLL atelectasis. I cant tell because I cant see where the left major fissure and the left hilum are. But I think I see air bronchogram in the profil view. The cause might be retained/forgotten surgical material.

Good answer. Did you read Gus’ opinion?

Do you think there is pericardial fluid?

I always read Gus’s opinion 🙂

I don’t know if there is pericardial fluid or not, but I think that I can see air around the heart shadow (in the profil view) which continues behind the trachea all the way up.

Maybe this retained surgical material provoked pneumopericardium-pneumomediastinum.

But don’t see anything in the AP view …

GUS HELP !!!!

🙂 ok

fistula post inflamation between esophagus and pericardium?

i think post inflamation is not correct answer (is too short period). iatrogenic is better.

OK, leave it there. Answer on Friday

..potrebbe essere una complicanza della intubazione tracheale, con fistola tracheo-esofagea, il che spiegherebbe sia la polmonite, da aspirazione , a carico del lobo polmonare inferiore sx, sia il pneumomediastino.

Might be a stupid answer, but my guess is it’s either a slow, continuous, but limited “blood leaking” caused by the sternal wire in the chest cavity resulting in a small amount of haemothorax and haemopericardium (that’s why the pleural effusion seems to be “demarcated” anteriorly)…. or it might be an infection caused by that same wire, resulting in a pneumonia and small amount of pyothorax in the LLL + pus leaking into the pericardial cavity, causing pyopericardium… might be way off the mark, but these are the things I could come up with… 😉

There are no stupid answers in this blog. The important thing, if one’s wrong, is to review the case and learn why the answer was incorrect.

And hope to be right the next time!