Dr. Pepe’s Diploma Casebook: Case 80 – SOLVED

Dear Friends,

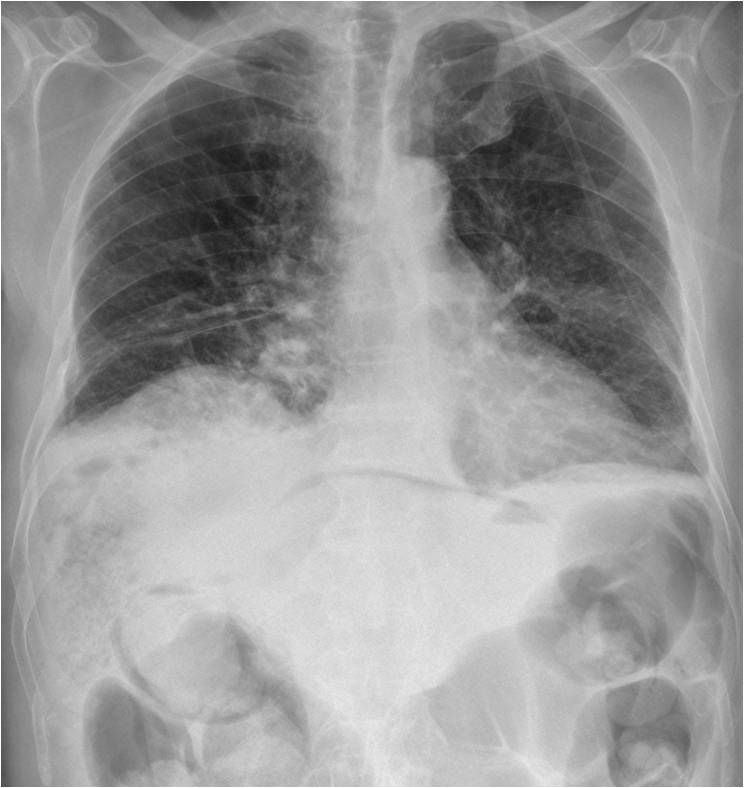

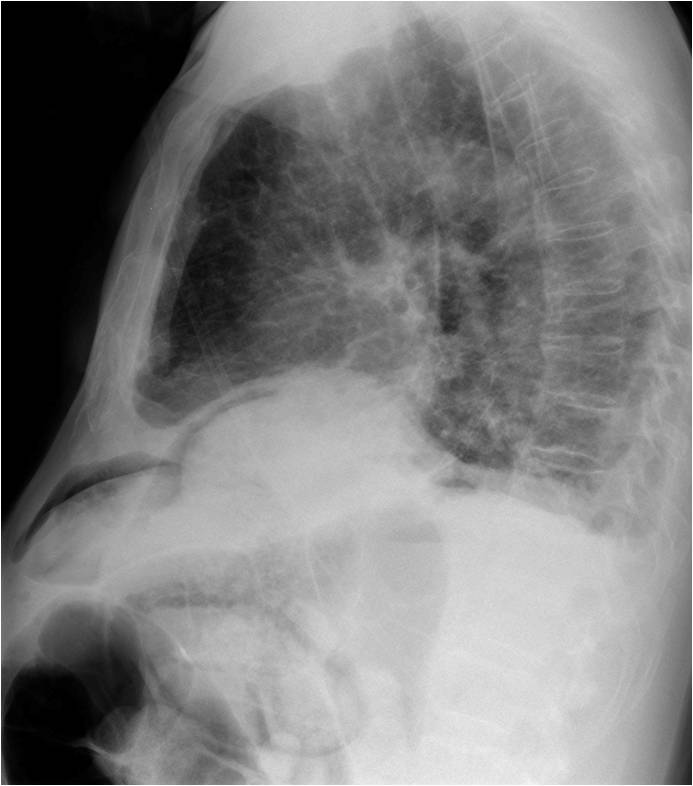

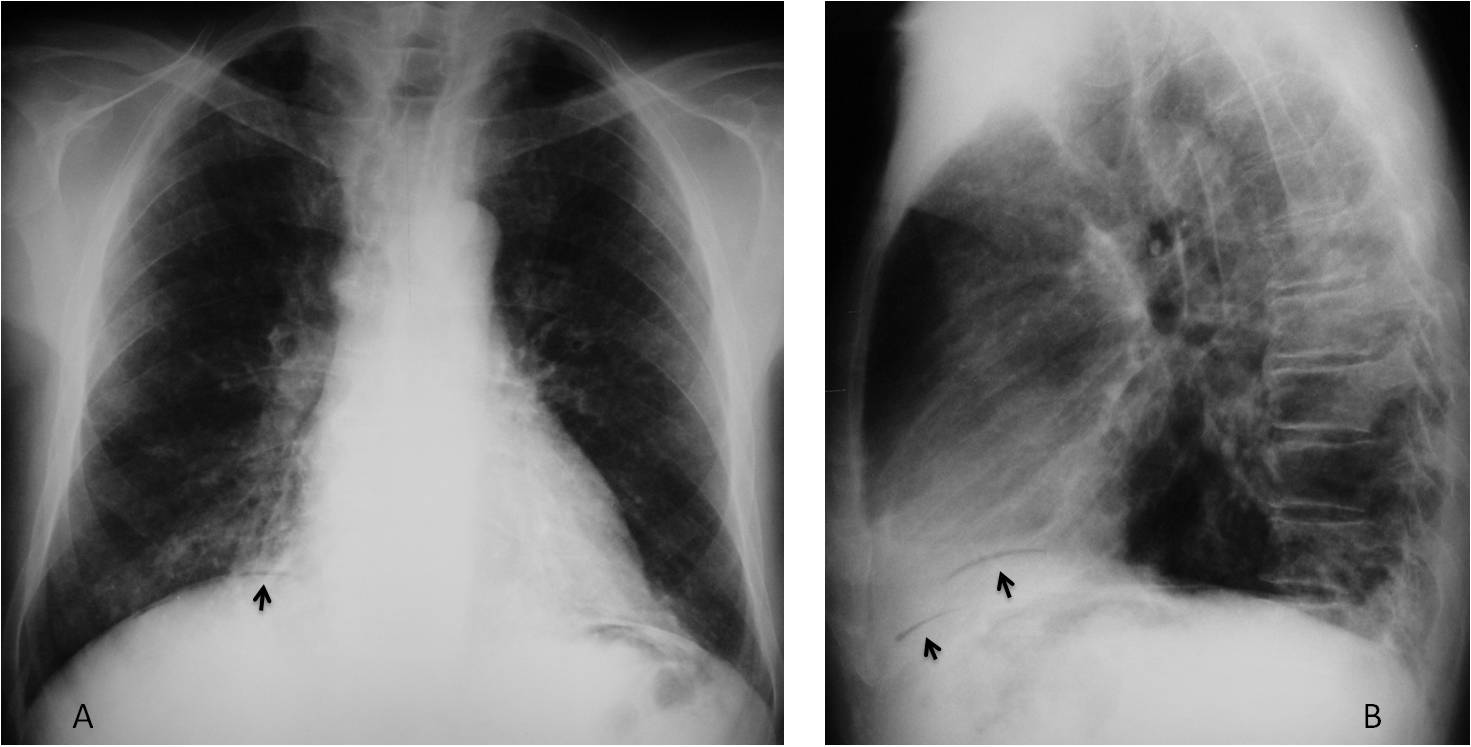

Presenting chest radiographs of an 80-year-old man. Images were taken 24 hours after embolisation of hepatic metastases. What do you see?

Check the images below, leave your thoughts in the comments section and come back on Friday for the answer.

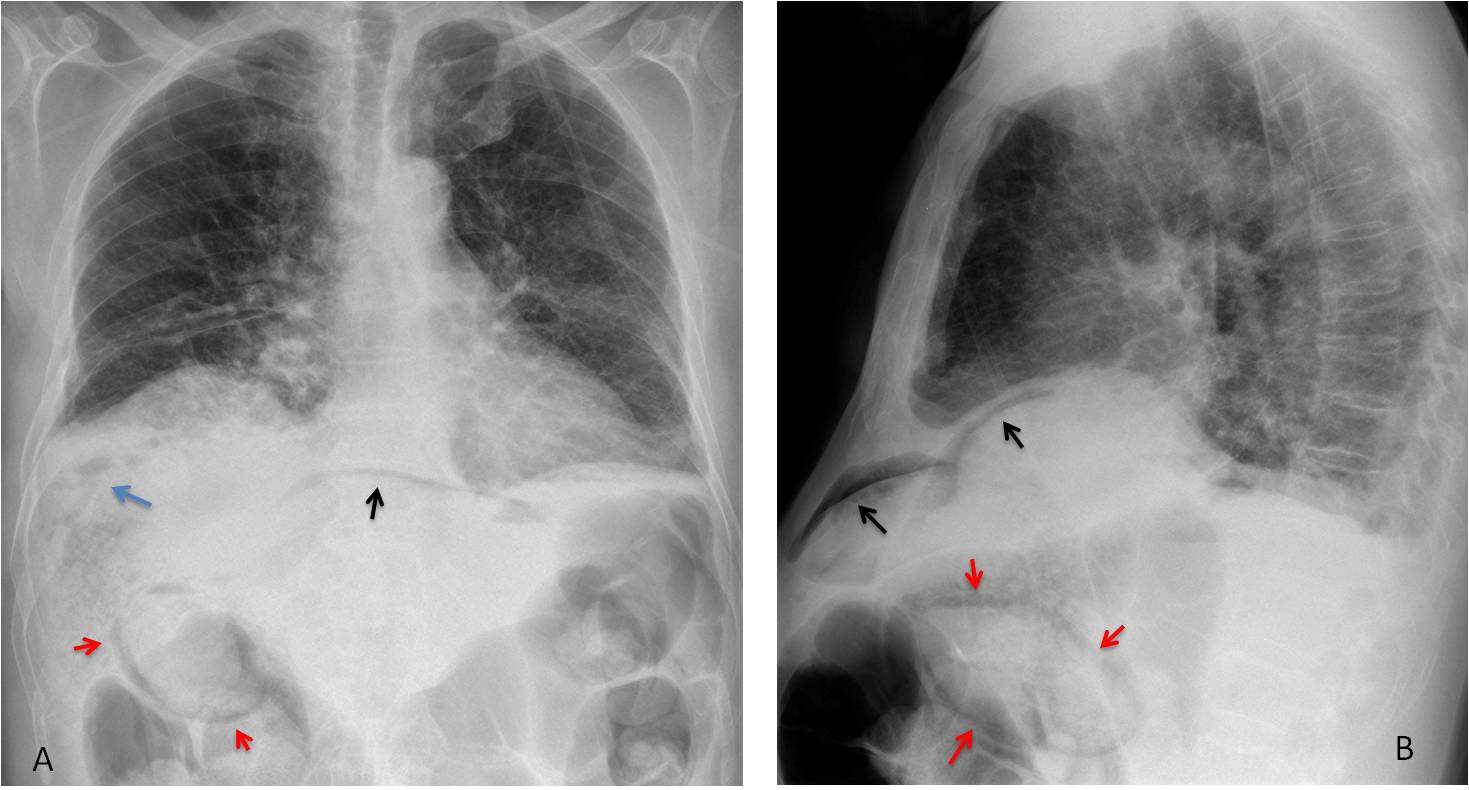

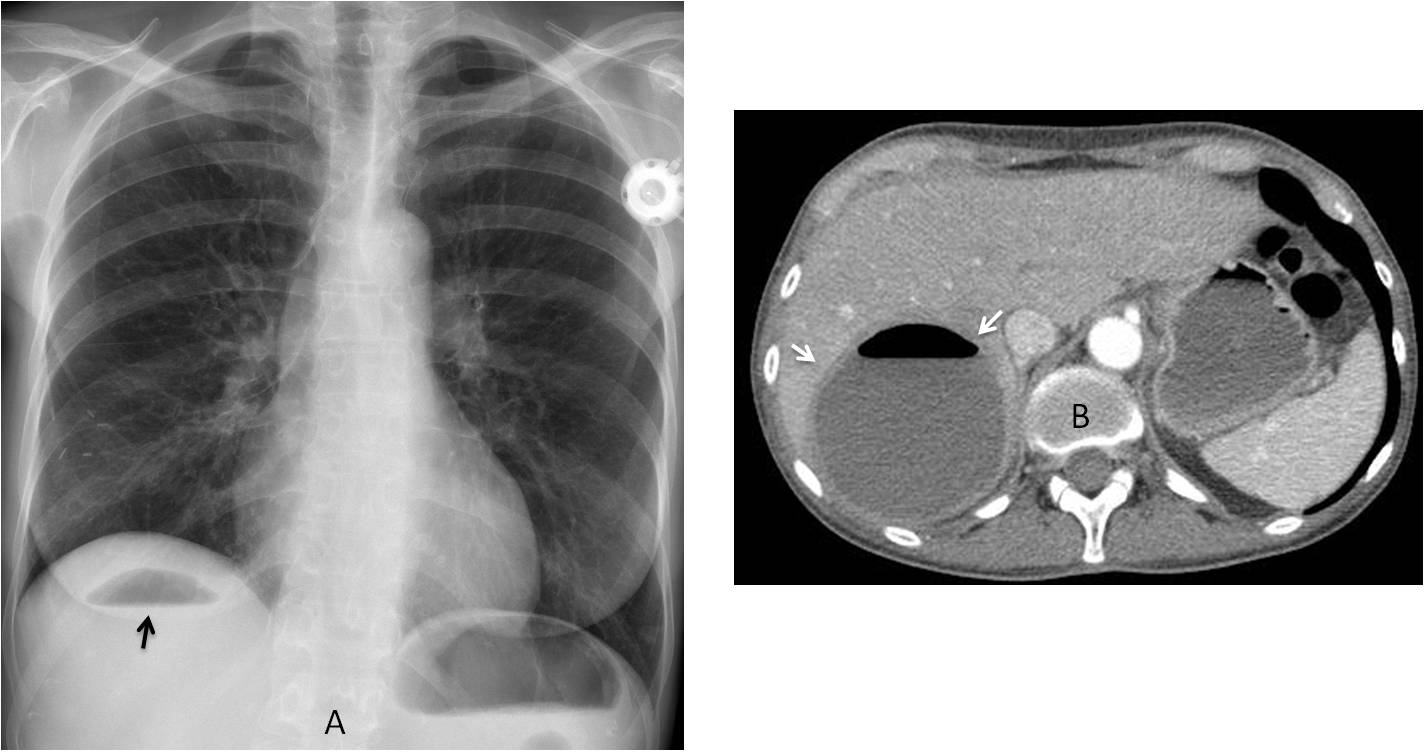

Findings: chest radiographs show nondescript pulmonary infiltrates. The main findings are seen below the diaphragm: pneumoperitoneum (A and B, black arrows), air within the liver (A, blue arrow) and air in the wall of the gallbladder (A and B, red arrows).

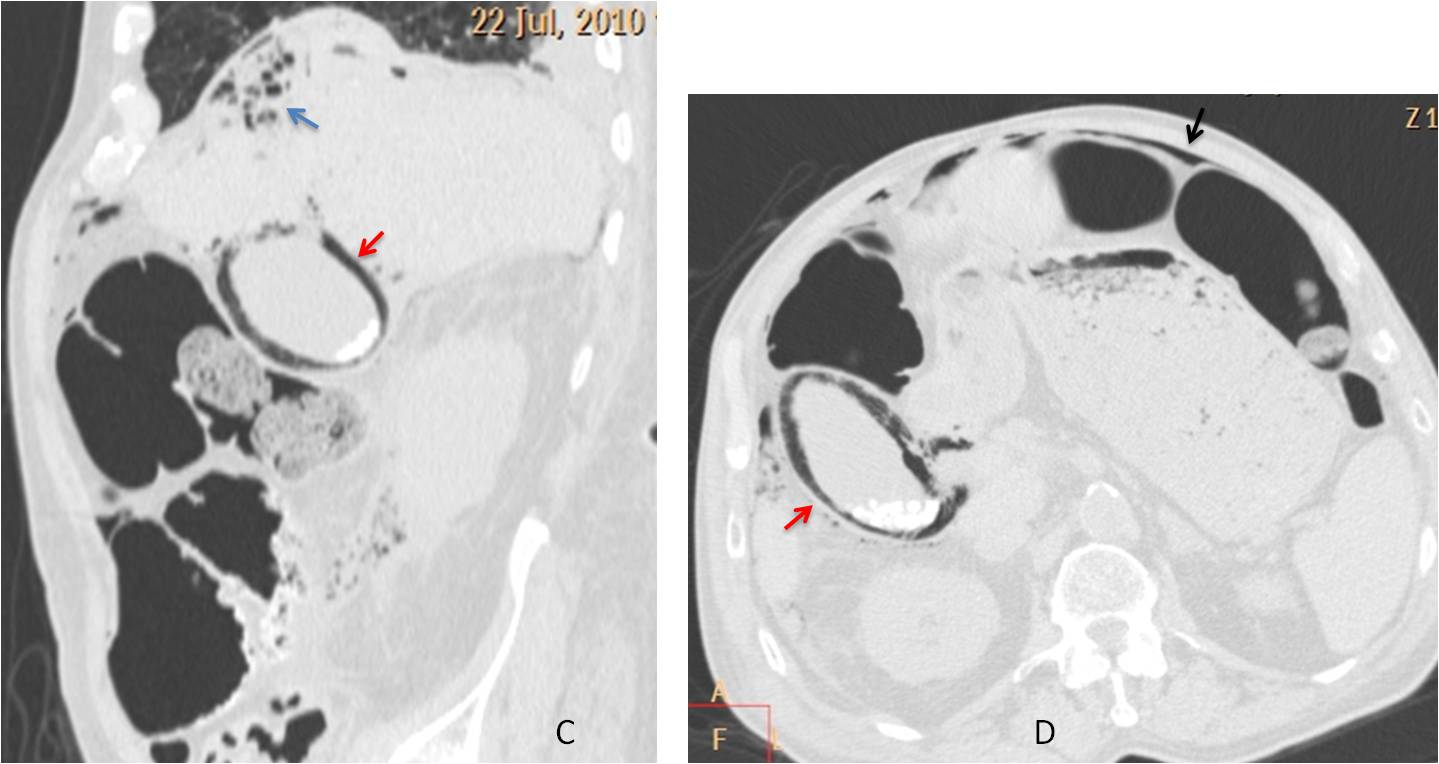

Sagittal and axial CT confirm the air within the liver (C, blue arrow), free abdominal air (D, black arrow) and air in the gallbladder wall (C and D, red arrows). These findings are a consequence of faulty embolisation. The patient died shortly afterwards.

Final diagnosis: pneumoperitoneum and emphysematous cholecystitis after embolisation.

The purpose of this presentation is to discuss the upper abdomen in the chest radiograph. Depending on body build, a sizable part of the abdomen may be depicted in the chest radiograph. This region should be included in the search for abnormalities in the same way as the components of the thorax.

In this presentation I will deal only with abdominal conditions that do not cause obvious abnormalities in the lower chest, such as diaphragmatic elevation, pleural effusion or basal pulmonary infiltrates. Abdominal findings that should focus our attention in the chest radiograph include abnormal air, calcium, and changes in size of the liver or spleen.

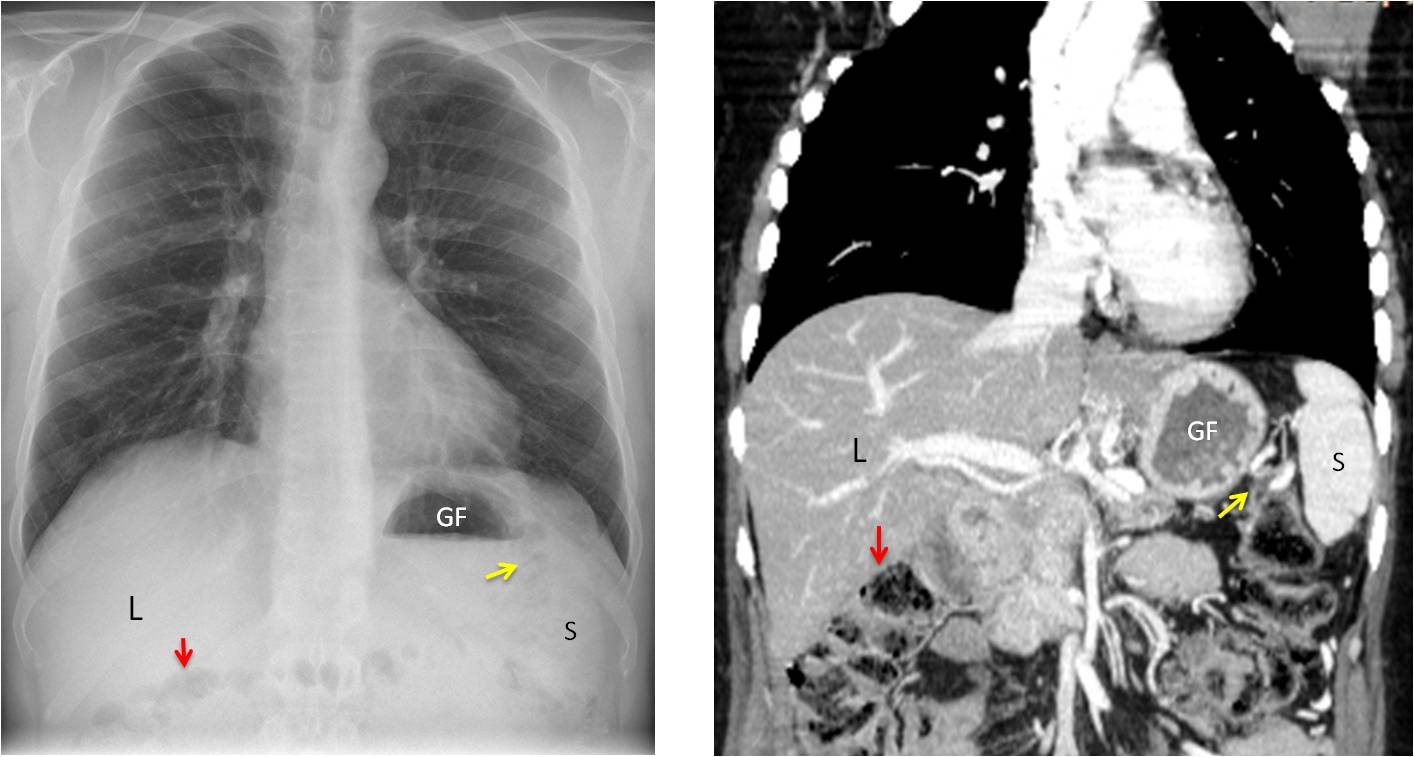

In the normal PA radiograph, the right upper quadrant of the abdomen is occupied by the liver, which appears of uniform soft-tissue density. The hepatic flexure of the colon is rarely included in the radiograph. When visible, it marks the lower margin of the liver and helps to assess liver size. The air-filled gastric fornix occupies the medial aspect of the left upper quadrant, with the splenic flexure of the colon and the spleen located laterally (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1: PA radiograph and coronal CT depicting the normal appearance of the upper abdomen. Liver (L), hepatic flexure (red arrow), gastric fornix (GF), splenic flexure (yellow arrow) and spleen (S).

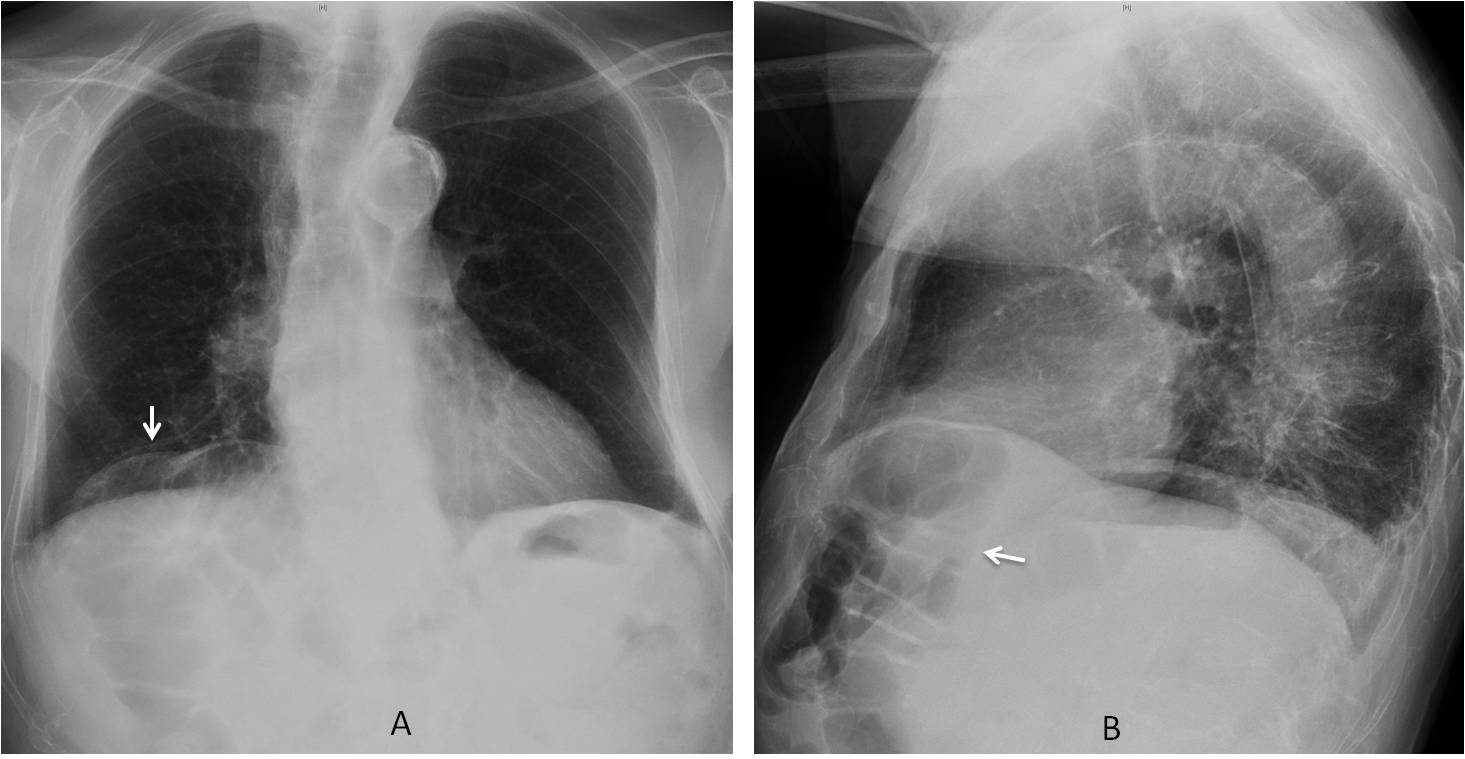

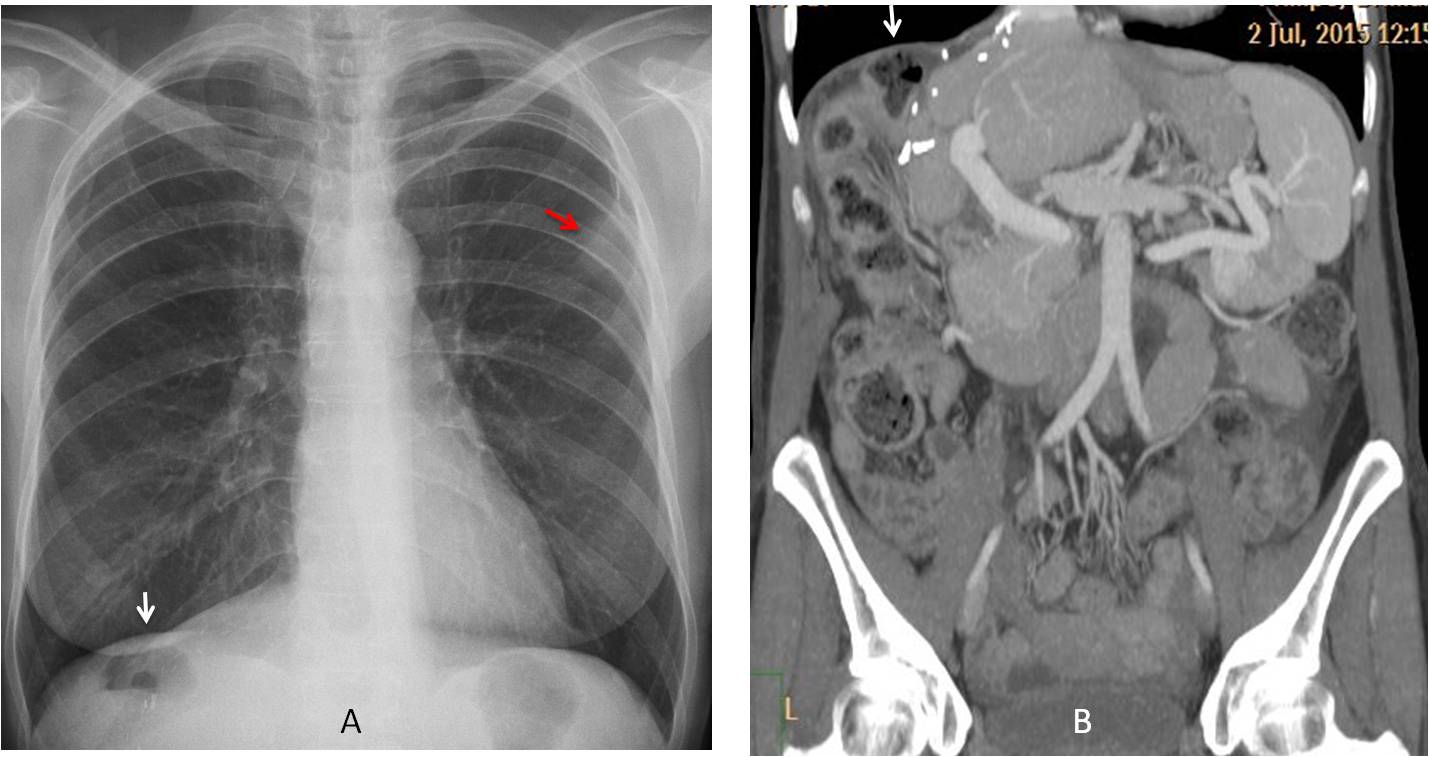

Colonic interposition (Chilaiditi syndrome) is a normal variant in which the hepatic flexure of the colon is elevated and located anterior to the liver. In the PA film it occasionally simulates pneumoperitoneum (Fig. 1). False Chilaiditi occurs in partial hepatectomy when the colon occupies the location of the partially removed liver (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 1: Chilaiditi syndrome. PA view shows the hepatic flexure of the colon above the liver (A, arrow). Lateral view demonstrates that the colon is not above, but anterior to the liver (B, arrow).

Fig. 2: False Chilaiditi syndrome. After partial right hepatectomy, the splenic flexure of the colon has risen, occupying the subphrenic space (A and B, white arrows). A metastatic nodule is visible in the left upper lung (A, red arrow).

The most obvious abnormality in the upper abdomen is anomalous air. It may be free, located under the diaphragm in the upright projection, or visible inside solid viscera or the wall of the bowel.

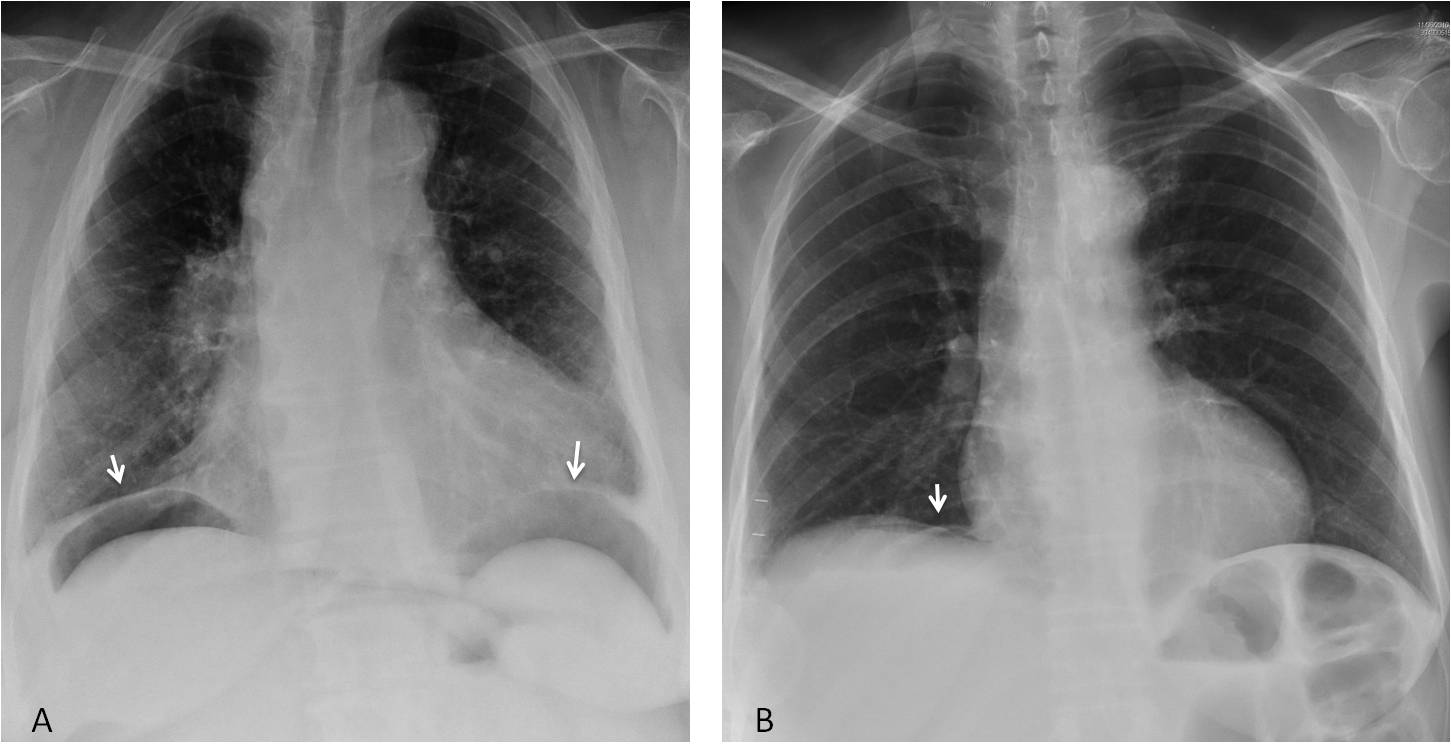

Pneumoperitoneum is probably the most common abdominal pathology seen in the chest radiograph. It may be large or barely visible (Fig. 3). When it is small, the chest radiograph demonstrates it more effectively than the upright view of the abdomen, because the free air is parallel to the X-ray beam. The main etiologies of free air are iatrogenic (abdominal intervention) or perforation of the bowel.

Fig. 3: Obvious abdominal free air in a patient with perforated diverticulitis (A, arrows). In another patient, the pneumoperitoneum is barely seen (B, arrow) and was not visible in the upright view of the abdomen.

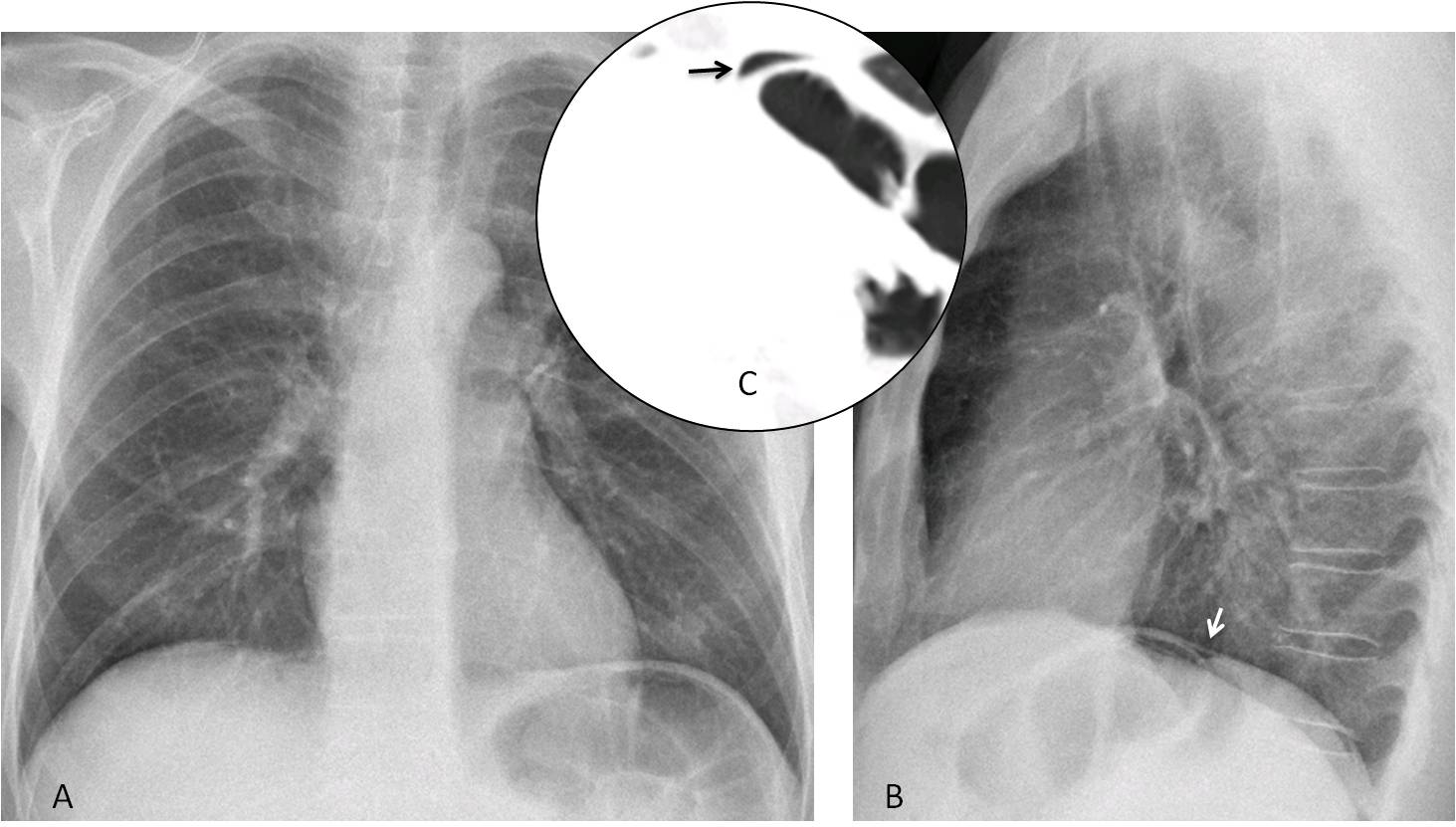

It should be emphasised that small amounts of free air are better seen in the lateral chest view, because air often locates anterior to the liver, offering a better interface to the x-ray beam (Figs. 4 and 5). Hence, it is very important to include a lateral view when examining the chest.

Fig. 4: Pneumoperitoneum barely visible in the PA radiograph (A, arrow) is better seen anteriorly in the lateral view (B, arrows).

Fig. 5: Pneumoperitoneum that is not visible in the PA radiograph (A) is seen in the lateral view (B, arrow). CT confirms a small amount of free air (C, arrow). Perforated ulcer.

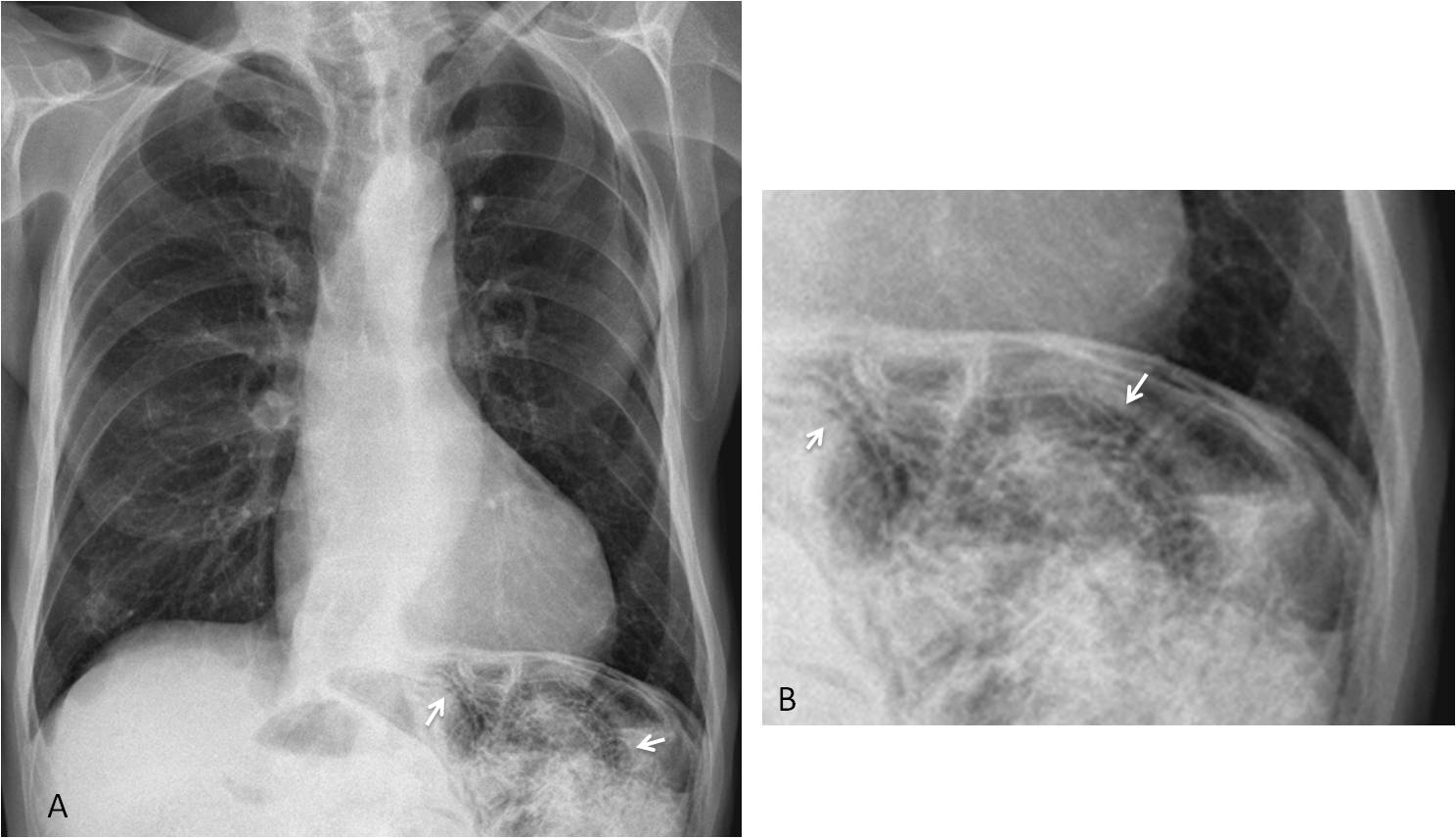

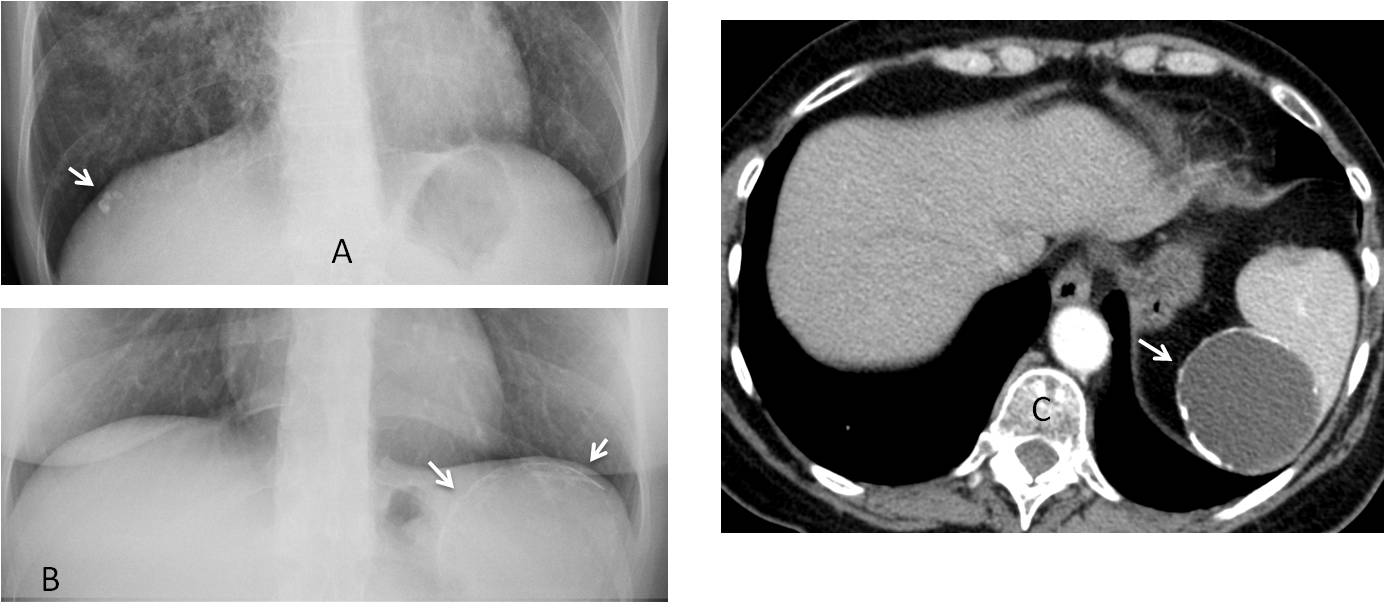

Air in the wall of hollow viscera may result from necrosis secondary to bowel ischemia or represent a benign process, pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis, related to migration of air from the chest in emphysema. It is seen as a dark line outlining the bowel wall (Figs. 6 and 7).

Fig. 6: 85-year-old man with weight loss. PA radiograph depicts bubbly appearance of the bowel in the left upper quadrant of the abdomen (A, arrows). Cone down view shows that this appearance is due to air in the bowel wall (B, arrows).

Sagittal and axial CT confirm the air in the bowel walls (C and D, arrows). No free air was seen. Diagnosis: pneumatosis cystoides intestinalis secondary to chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Fig. 7: 56-year-old woman with scleroderma. PA radiograph shows free abdominal air (A, white arrow) and bubbly appearance of the hepatic flexure of the colon (A, red arrow). Sagittal CT confirms the pneumoperitoneum (B, black arrow) and intramural air (B, red arrows). Scleroderma is known to cause pneumatosis. The findings resolved without treatment.

Air in solid viscera may be seen as an air-fluid level. Usually occurs in the right upper quadrant, secondary to a liver abscess (Fig. 8). As opposed to subphrenic abscess, which is accompanied by pleural effusion in about 80% of cases, liver abscess may not present secondary signs at the right lung base.

Fig. 8: 47-year-old woman with carcinoma of the breast and a liver abscess seen as an air-fluid level in the RUQ of the abdomen (A, arrow). Enhanced axial CT confirms the intrahepatic location of the abscess (B, arrows) (Case courtesy of Dr. Matthias Meissnitzer).

Amorphous calcium secondary to healed granulomas may be visible in the upper abdomen and should not be confused with calcified costal cartilages. Circular calcium is representative of a calcified cyst (hydatid cyst in endemic areas). Cysts are more common in the liver, but they may be seen in the spleen as well (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9: Calcified granulomas in a patient with active TB (A, arrow). Circular calcification in the left upper quadrant (B, arrows), confirmed with enhanced CT to represent a simple cyst of spleen (C, arrow).

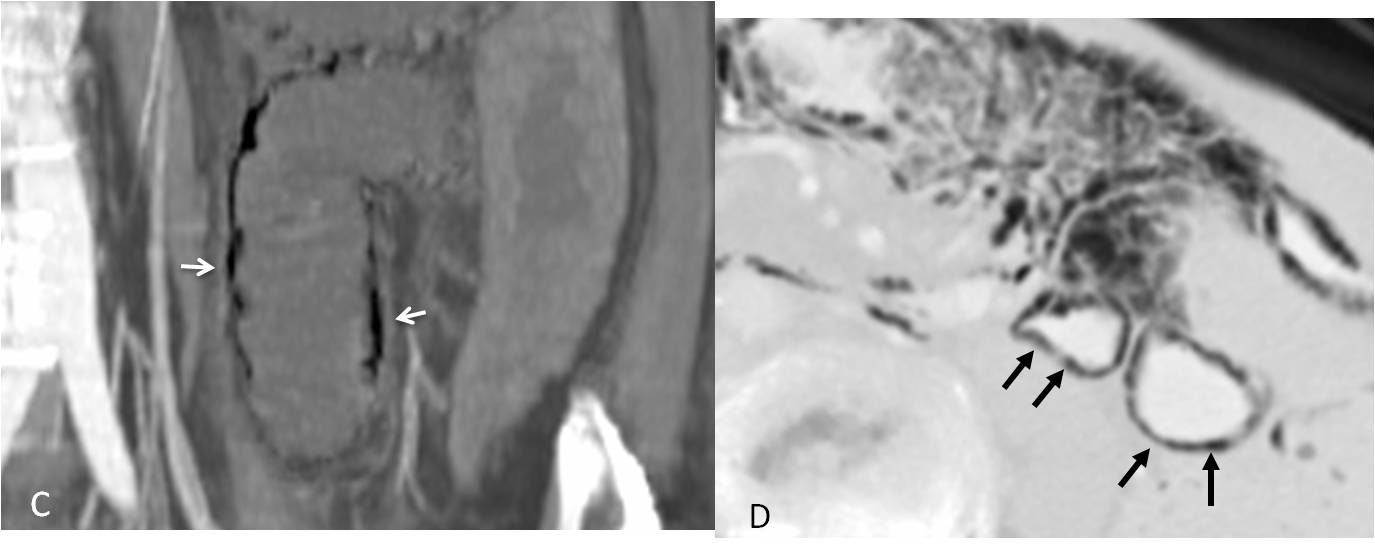

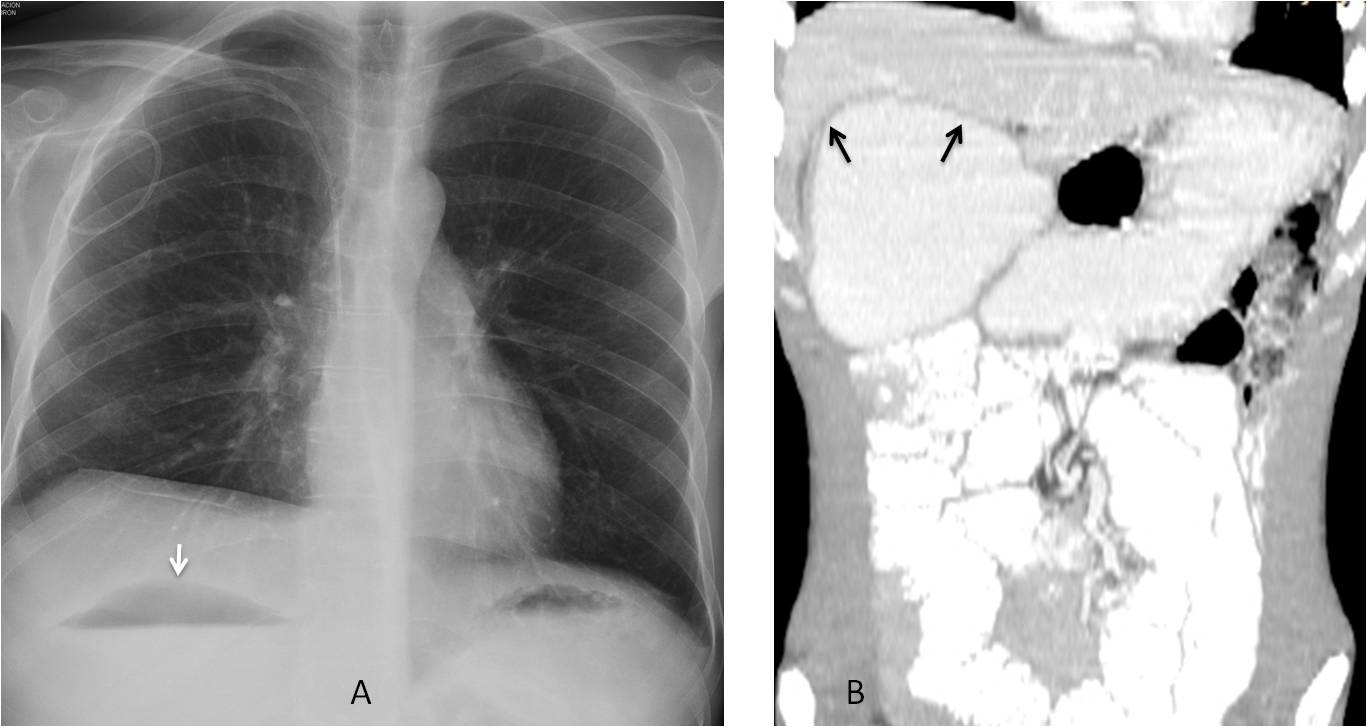

Hepatomegaly is difficult to ascertain in the PA chest radiograph unless the hepatic flexure of the colon is included in the film. A small liver is easier to detect when bowel gas is elevated, marking the caudal end of the liver (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10: 34-year-old man with severe intestinal malabsorption syndrome. The air-fluid level in the dilated duodenum marks the inferior limit of the liver in the PA chest film (A, arrow). Liver atrophy is obvious in the coronal CT image (B, arrows).

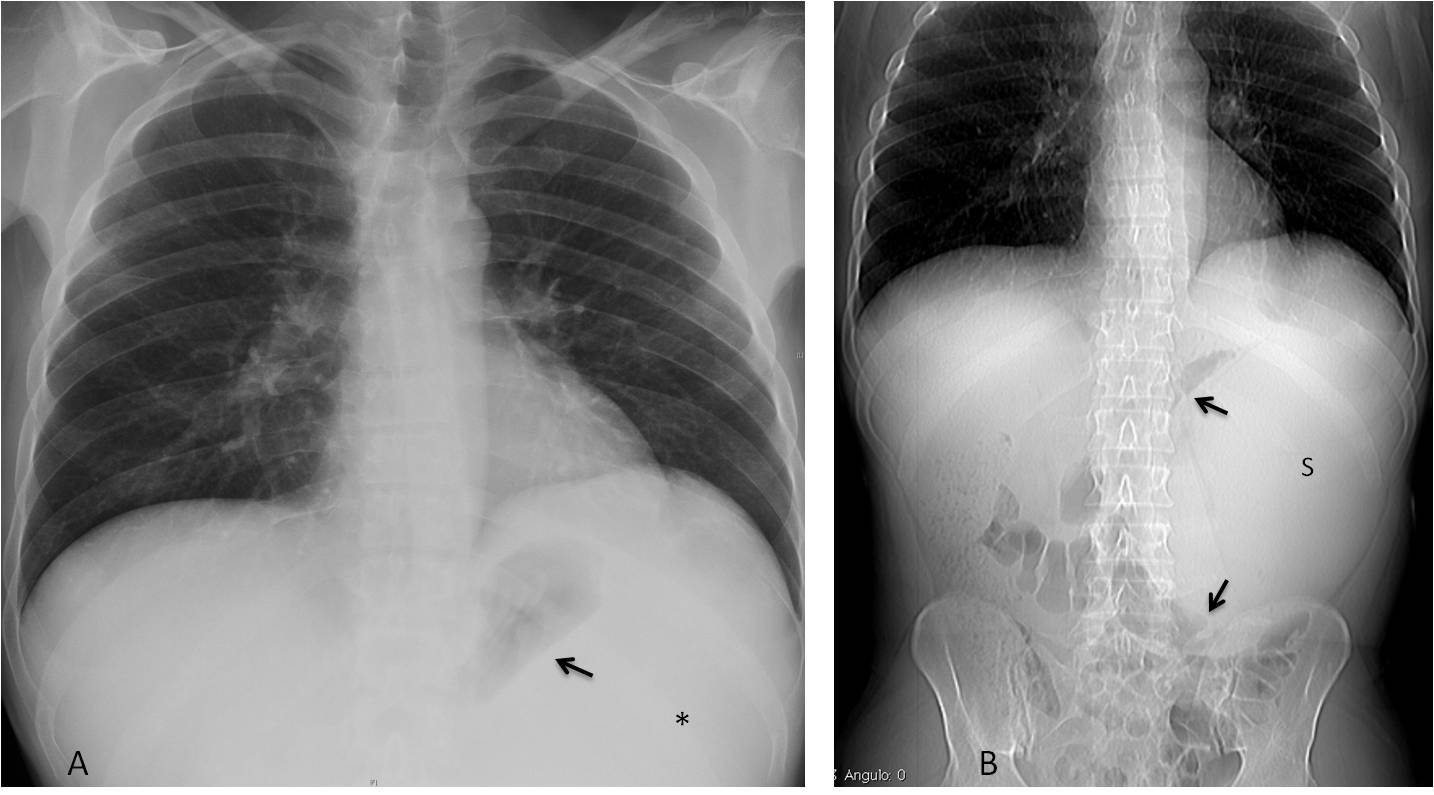

Splenomegaly is easily identified because the enlarged spleen displaces the gastric fornix medially and the splenic flexure downwards, giving a uniform soft-tissue density of the left upper quadrant.

Fig. 11: 54-year-old man with fever and malaise. PA chest film shows medial displacement of the gastric air (A, arrow) and uniform opacity of the LUQ (A, asterisk). Coronal CT shows a large spleen (S) displacing the stomach and splenic flexure (B, red arrows). Diagnosis: lymphoma.

Follow Dr.Pepe’s Advice:

1. Free abdominal air is better seen in the chest radiograph, especially the lateral view.

2. Intramural bowel air indicates ischemia or benign pneumatosis.

3. Circular calcifications in the upper quadrant correspond to cysts.

4. Splenomegaly causes medial gastric displacement.

gallbladder wall pneumatosis et pneumoperitoneum

Emphysematous cholecystitis with perforation causing pneumoperitoneum.

Sclerotic change on left first anterior rib. Hilar adenopathy.

…dopo TACE, si possono avere complicazioni….una di esse è legata alla ischemia prodotta dal materiale embolizzante , negli organi del tripode celiaco per un meccanismo di trasporto “retrogrado”….tra le strutture interessate vi è la colecisti e lo stomaco….una sofferenza ischemica può portare ad una colecistite e/o gastrite enfisematosa, con successiva perforazione e pn-peritoneo…in questo caso vi è inoltre una piccola falda di liquido nel seno costo-frenico….

Les agradesco por su pagina y por los caso son de gran ayuda saludos des de mexico gracias

Gracias por su opinión favorable. Es un estímulo para continuar.

Infarction of gallbladder with emphysematous cholecystytis and perforation with pneumoperitoneum as a complication of non intended embolization of cystis artery.

Apart from emphysematous cholecystitys and pneumoperitoneum all of you mentioned, I see (not sure, as always):

-Bilateral linear interstitial pattern, more pronounced in bases. With clinical history of malignancy could be related to carcinomatous lymphangitis (compare with previous x-ray would help).

-Small bilateral pleural effusion without cardiomegaly.

-Distended colon, ¿obstruction?.

I believe the increased markings are due to difficult breathing. There was no colonic obstruction. Dilatation was probably secondary to mesenteric emboli or general distress. An autopsy was not done.

There is an air in the gallbladder wall and in peritoneum, and probably also pneumobilia.In the chest there are signs of interstitial thickening,also spaces along bronchi and vessels ,volume of RLL is reduced – downward replacement of small fissure and right hilum. Acording to initial diagnosis it sugest hilar metastases and lymphangitis.

Small amount of fluid in both pleural cavities.

I am very proud of all of you. 100% correct diagnosis, led by Dr. Aloria.

Beware of case 81, next Monday. It is going to be more difficult,

…quando il gioco si fa duro …… i duri iniziano a giocare….