Dr. Pepe’s Diploma Casebook: Case 85 – SOLVED!

Dear Friends,

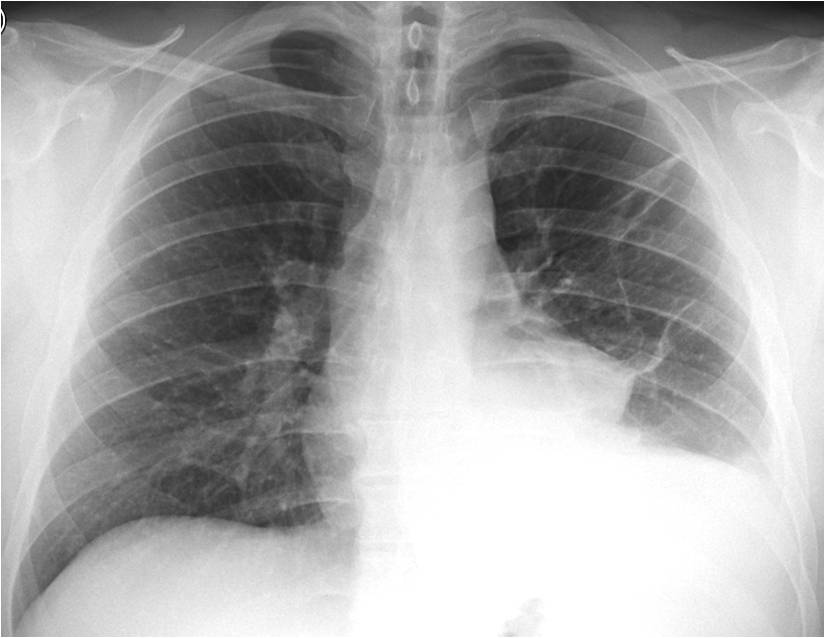

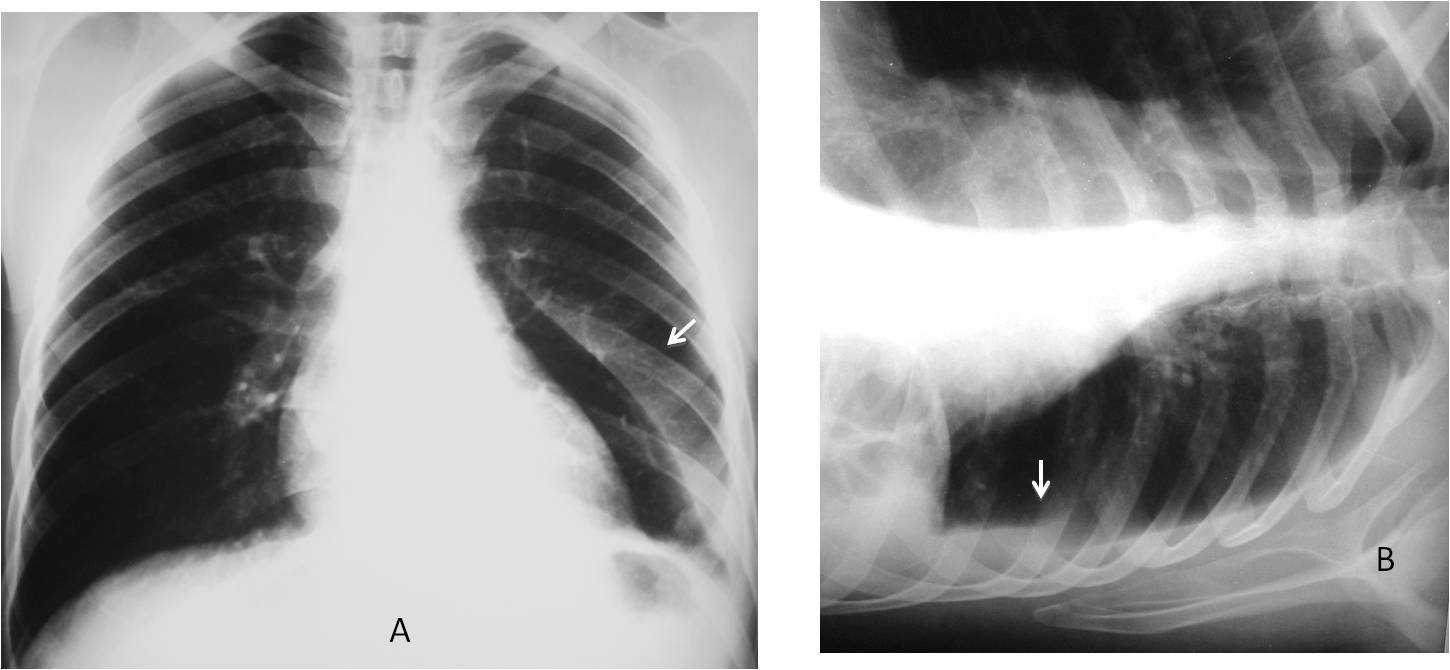

Today we are presenting chest radiographs of a 54-year-old man who has had a cough and left chest pain for the last two weeks. No fever.

Check the images below, leave your thoughts in the comments section and come back for the answer on Friday.

Diagnosis:

1. Pleural effusion

2. Pleural effusion and mediastinal mass

3. Pleural effusion and pericardial defect

4. None of the above

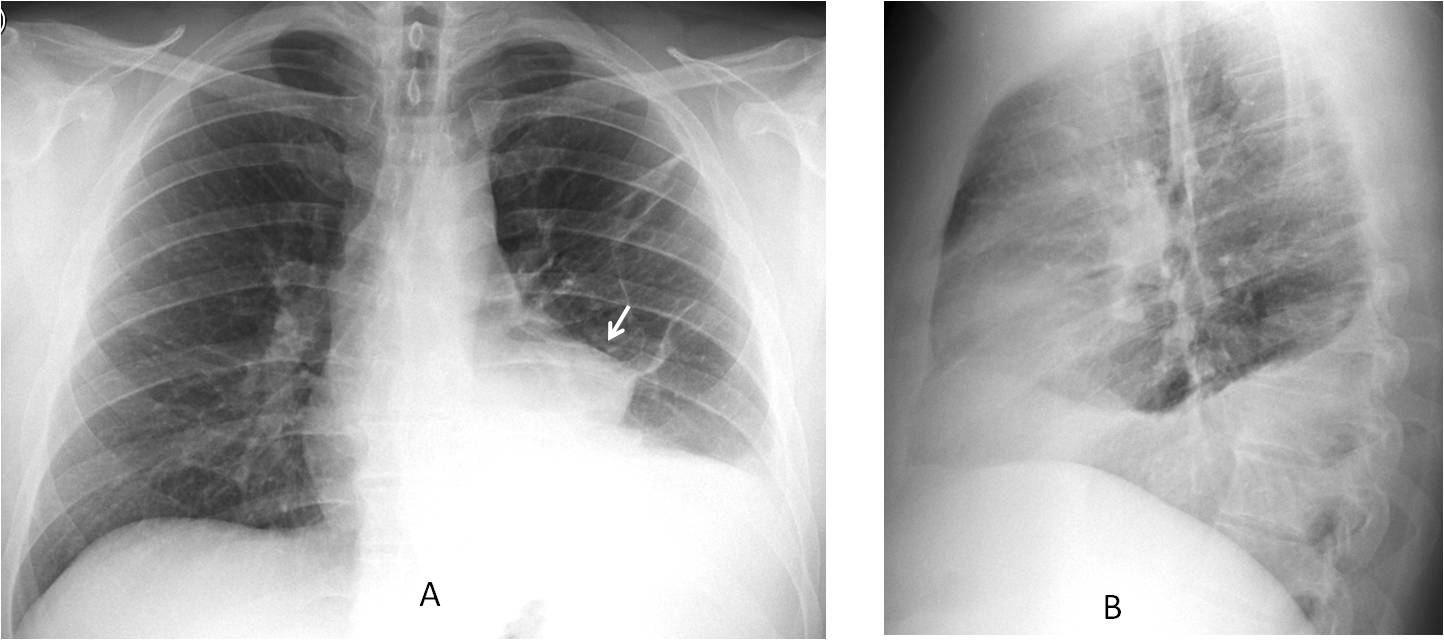

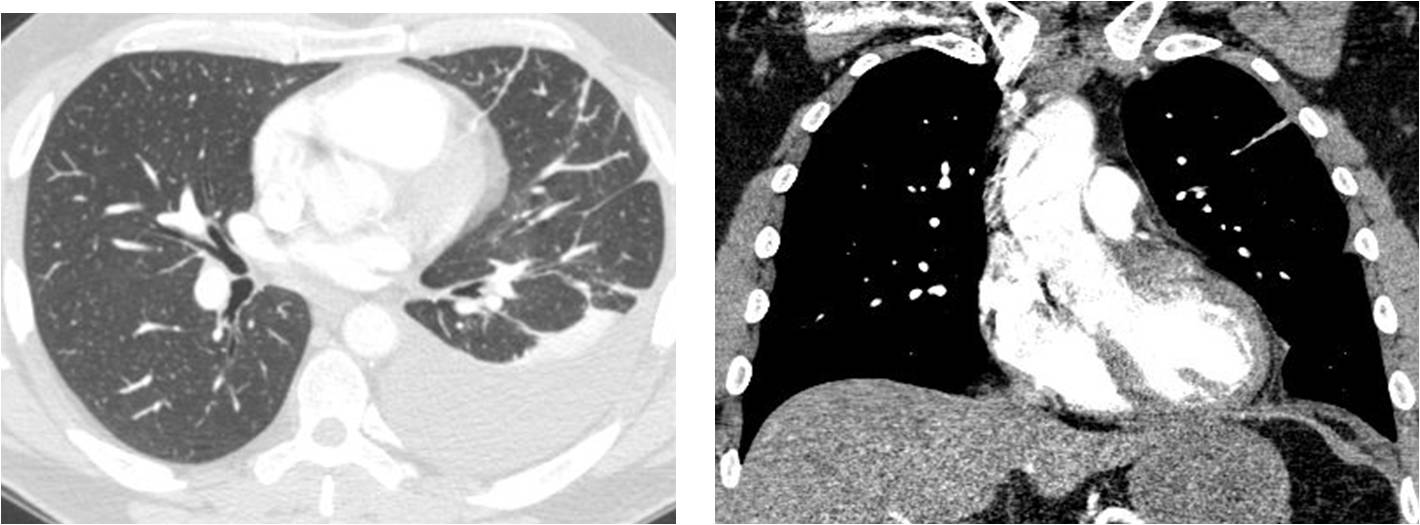

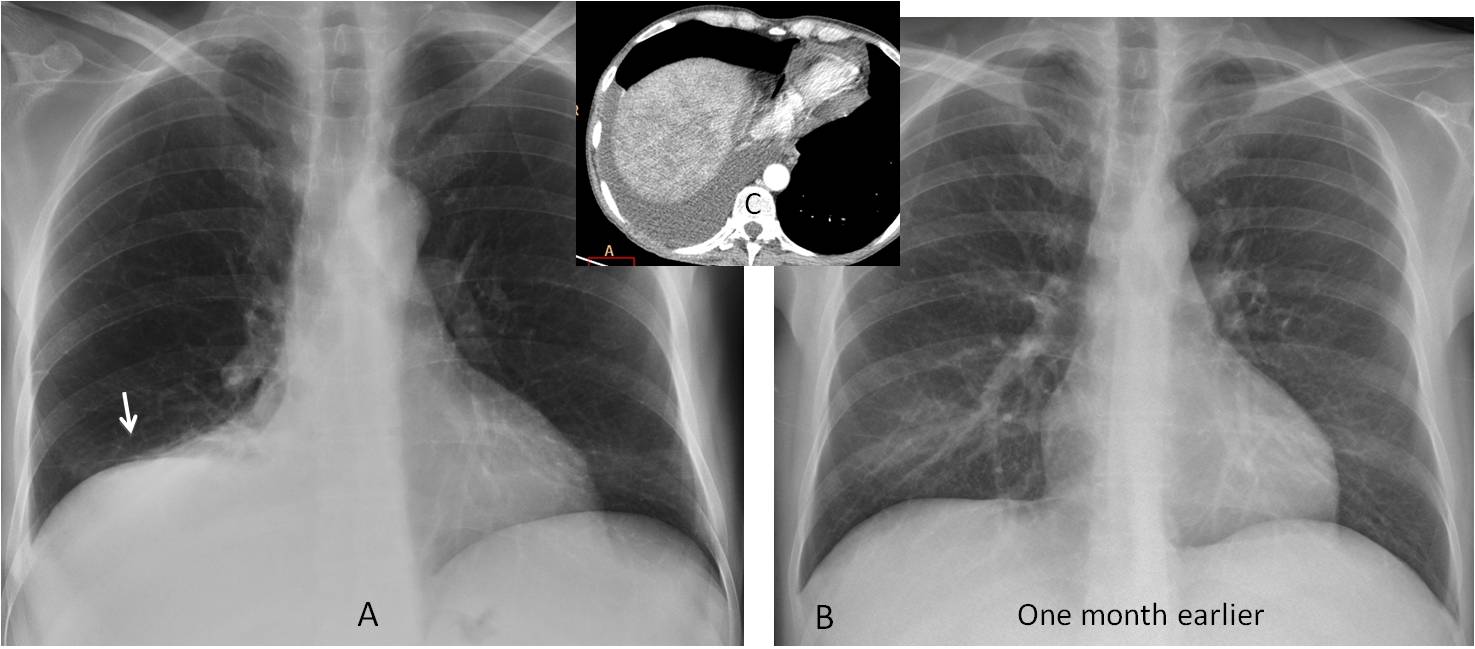

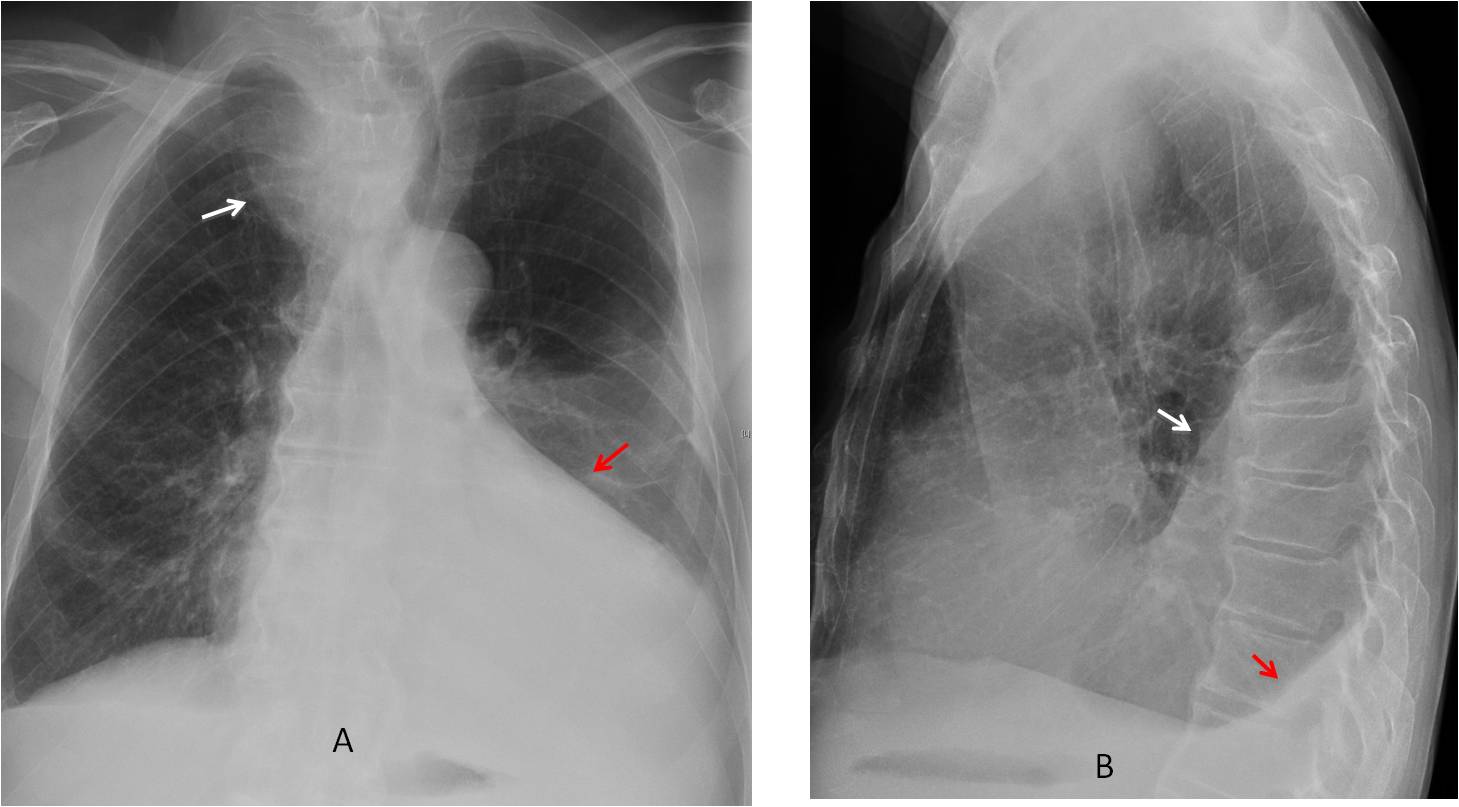

Findings: chest radiographs show linear infiltrates in the left lung, pleural effusion, and bulging of the mediastinum, suspicious for a mediastinal mass (A, arrow).

Enhanced axial and coronal CT images exclude a mass. Only the linear infiltrates and pleural fluid are visible. The patient was diagnosed with pulmonary embolism, with resolution of the findings.

Final diagnosis: pulmonary embolism with free pleural effusion simulating a mediastinal mass.

Identification of pleural fluid in the chest radiograph is important because of its clinical significance. Free pleural effusion is easily recognised most of the time. Occasionally, it may have an atypical appearance, leading to an incorrect diagnosis. In this presentation I would like to discuss common and uncommon manifestations of free pleural fluid in the upright chest radiograph.

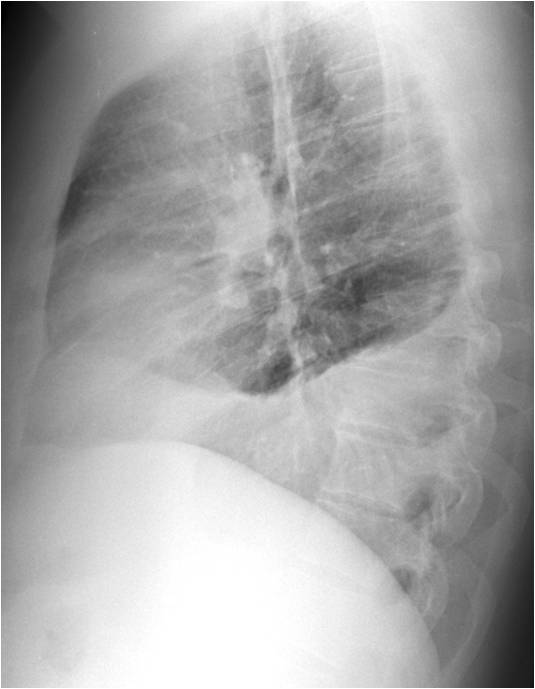

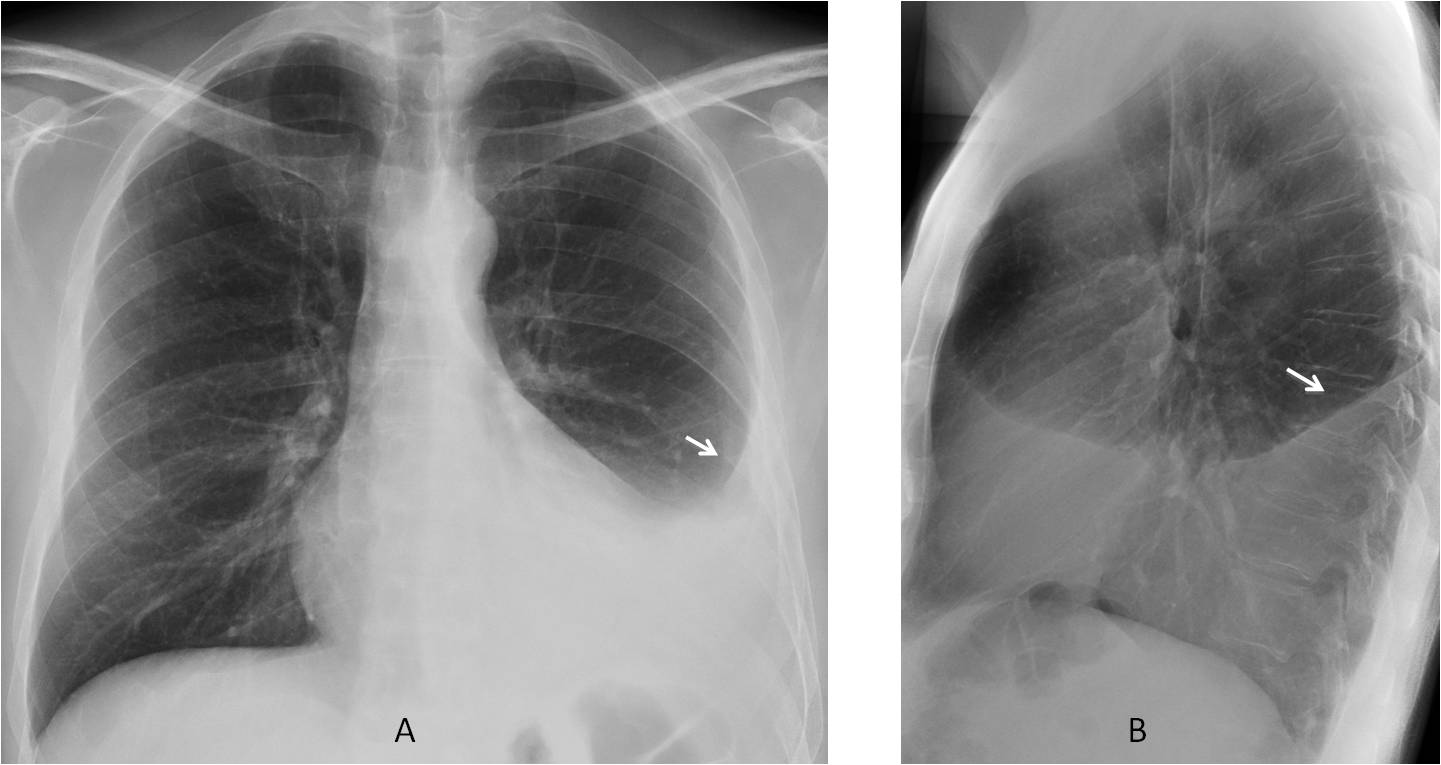

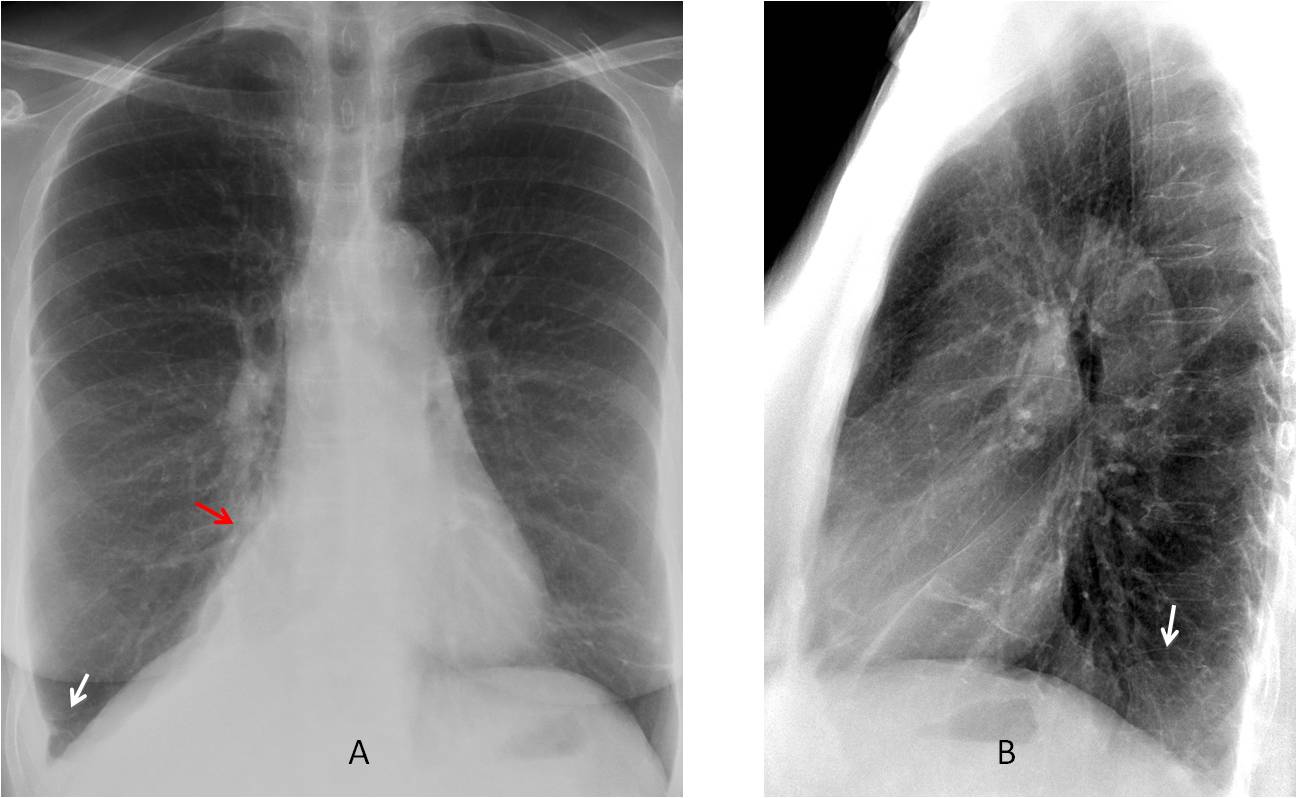

In upright PA and lateral radiographs, free pleural fluid usually appears as a typical concave meniscus line with blunting of the costophrenic angles (Fig. 1).

Fig .1

Fig. 1: chest radiographs showing the typical appearance of free pleural fluid, with the upper meniscus higher in the lateral and posterior walls, and obliteration of the costophrenic sulcus (A and B, arrows).

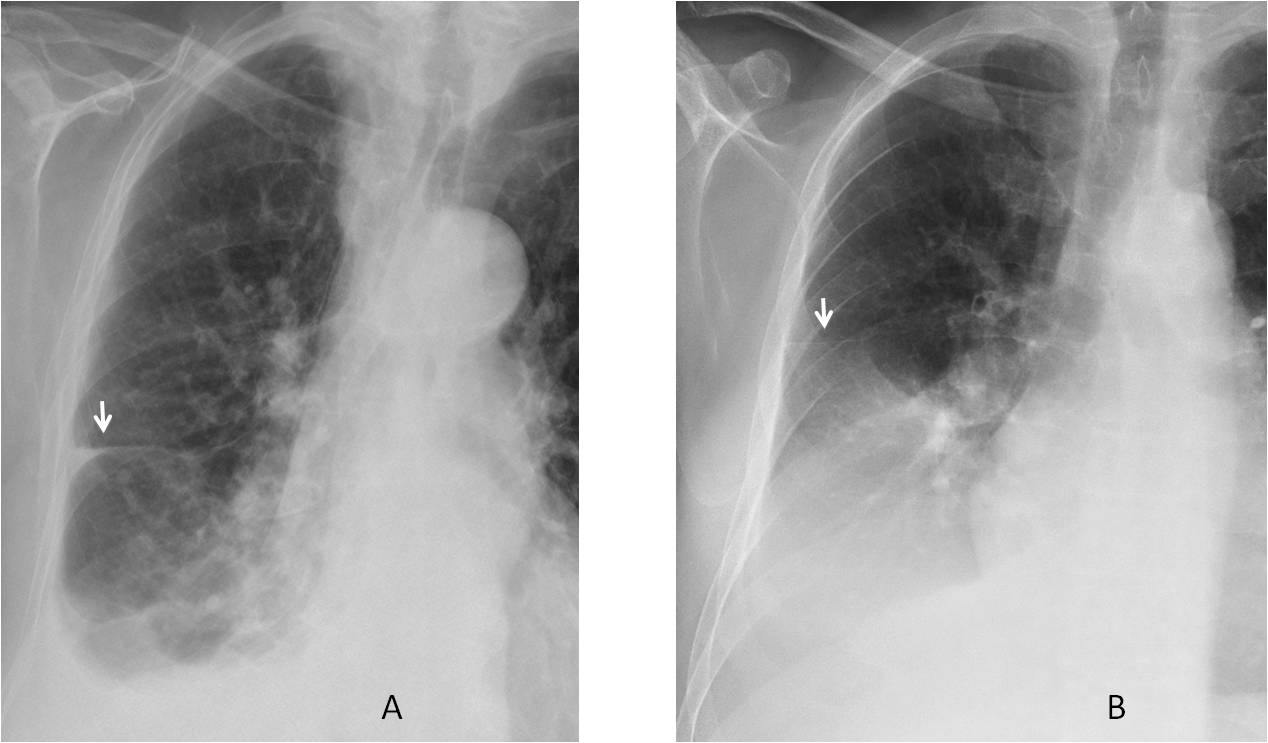

In the right hemithorax, the fluid may have a straight upper border (middle lobe step), believed to be caused by an incomplete middle fissure (Fig. 2). This finding has no clinical significance.

Fig. 2

Fig. 2: two patients with right pleural effusion showing the middle lobe step (A and B, arrows).

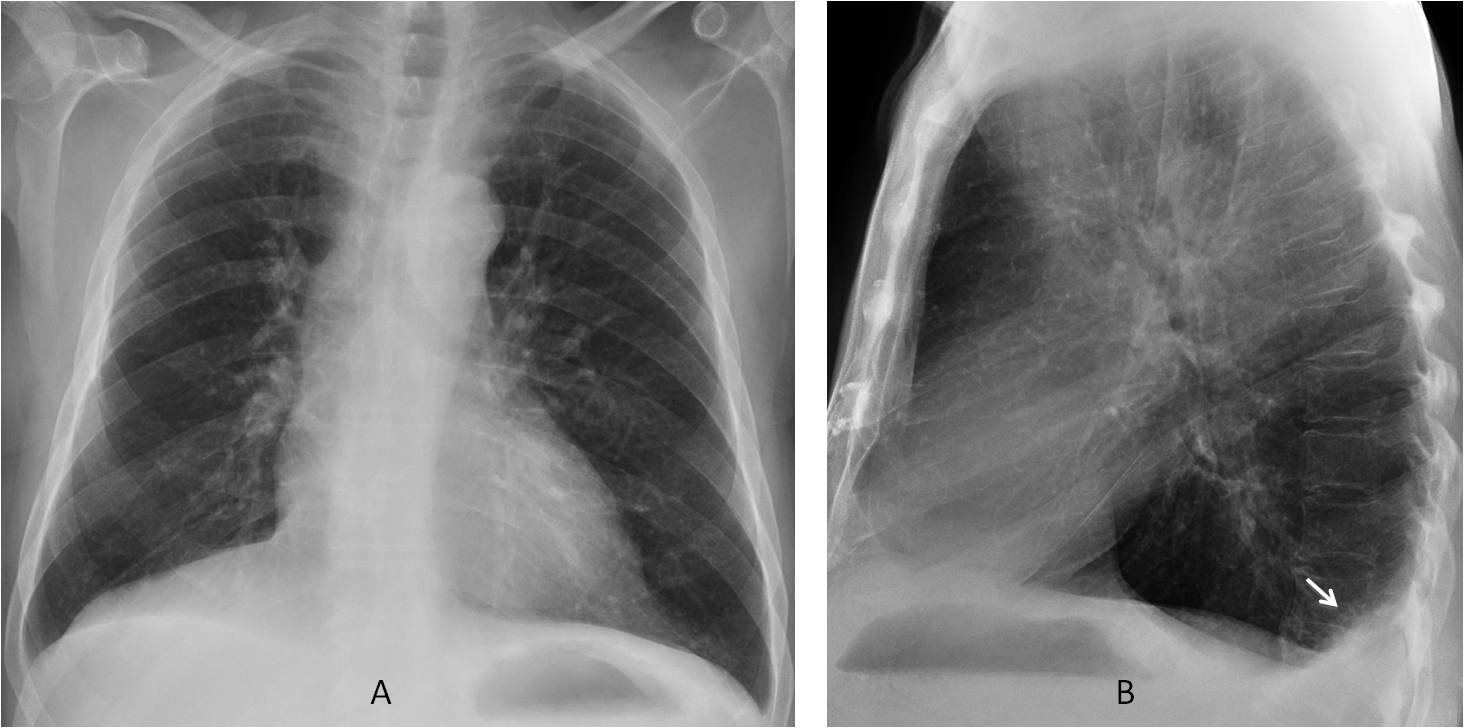

It’s important to mention that pleural fluid can collect in the posterior sulcus before it is visible in the PA chest film. This emphasises the importance of the lateral view for prompt discovery of pleural effusion (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3

Fig. 3: left pleural effusion undetected in the PA radiograph (A), but clearly visible in the lateral view (B, arrow).

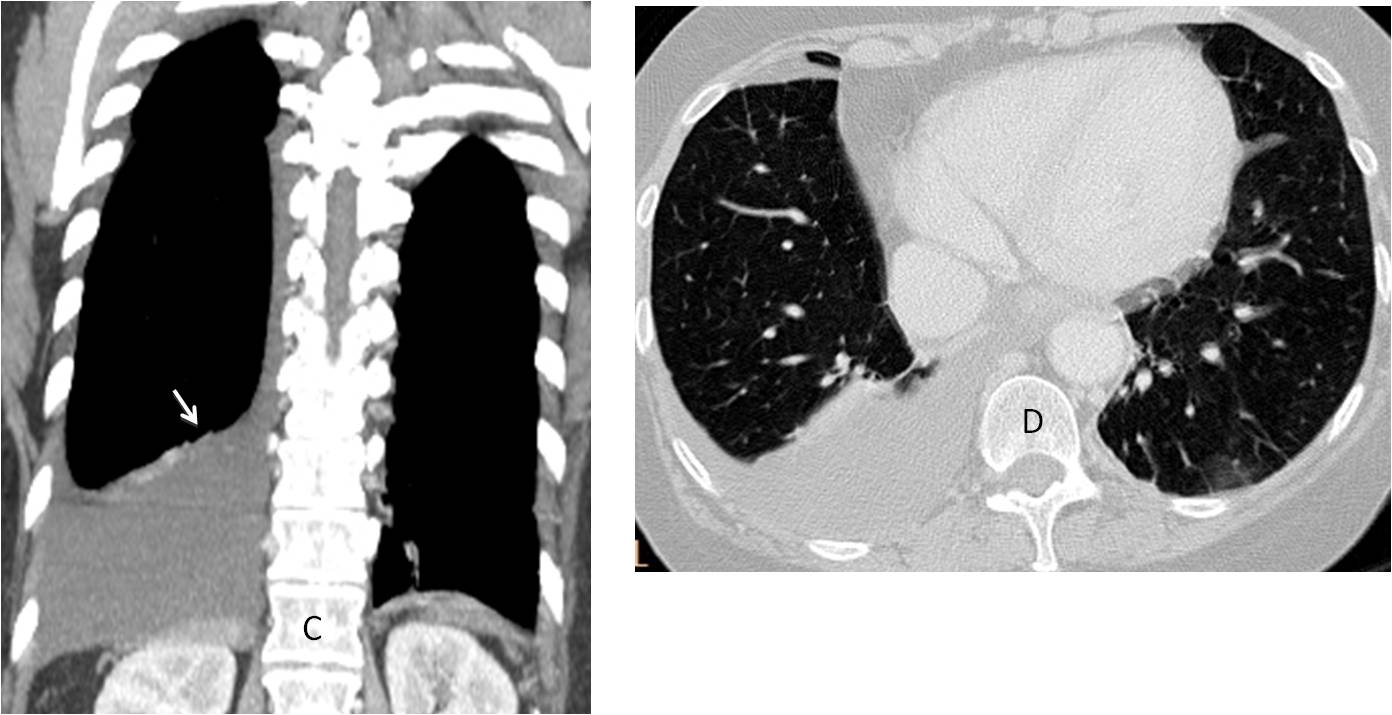

Subpulmonary effusion, occurring when fluid interposes between the lower lung and hemidiaphragm, is by far the most common atypical presentation of free fluid. It appears as an apparently elevated hemidiaphragm, more opaque than its counterpart (Fig. 4). Subpulmonary effusion is confirmed with a lateral decubitus view or ultrasound study.

Fig. 4

Fig. 4: patient with liver cirrhosis and subpulmonary effusion, suspected because the right hemidiaphragm appears elevated (A, arrow) and more opaque that the left. The changes are more obvious when this image is compared with a radiograph taken one month earlier (B). CT confirms the fluid (C, insert).

The lateral view is very helpful for detecting subpulmonary fluid, showing abnormal curvature of the hemidiaphragm and blunting of the posterior costophrenic sulcus (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5

Fig. 5. Subpulmonary effusion, suspected because the right hemidiaphragm seems to be elevated and denser that the left (A, arrow). The lateral view shows the abnormal curvature of the apparent right hemidiaphragm and blunting of the posterior costophrenic sulcus (B, arrow).

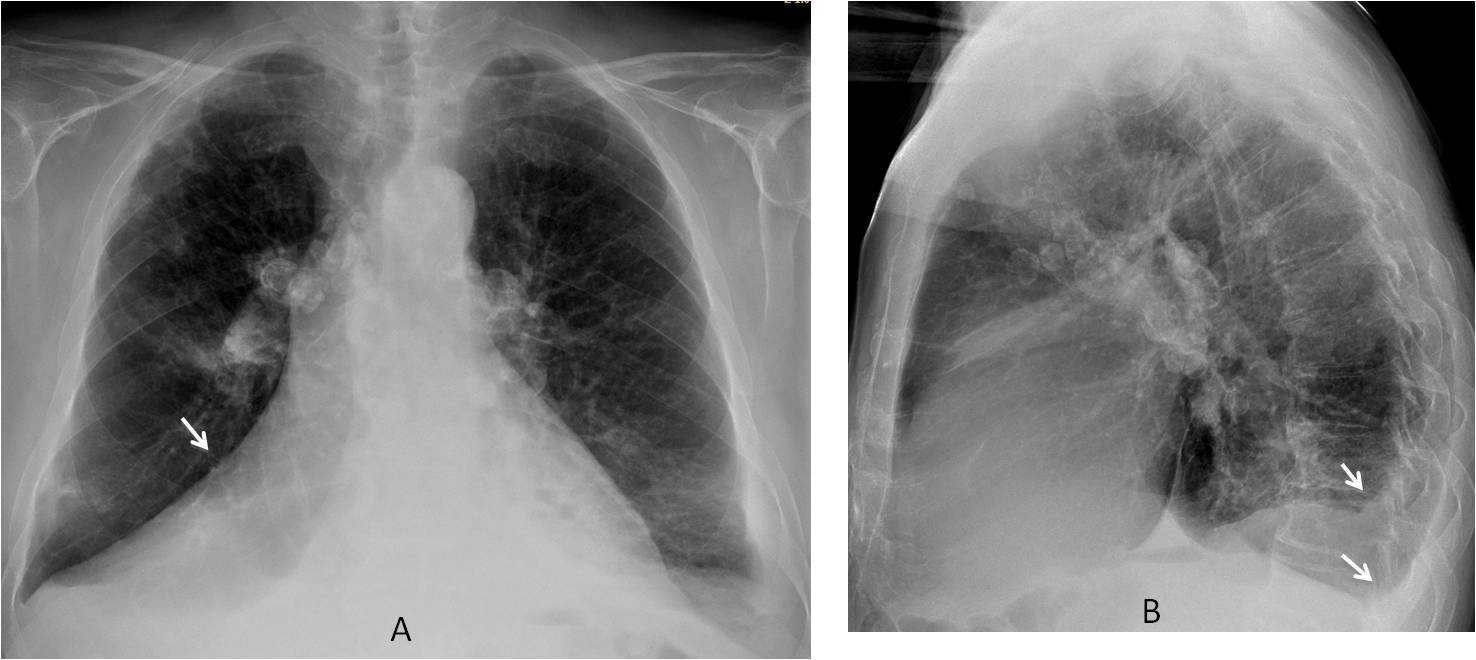

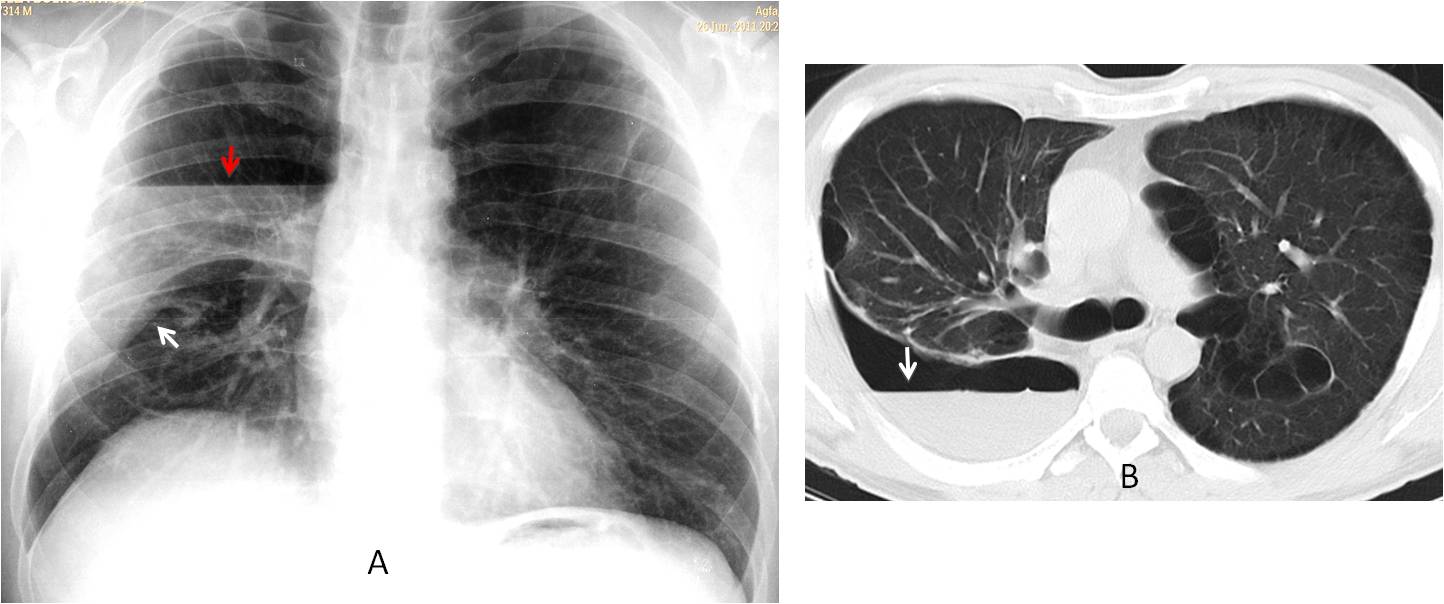

There are other, less common atypical patterns of free effusion. The fluid may rise higher on the mediastinal side than the lateral side, simulating lower lobe collapse. Because of the medial location of the fluid, the lateral view may not show the typical appearance, either (Figs. 5 and 6). The fact that the hilum is not descended helps to suggest the correct diagnosis.

Fig. 5: PA radiograph shows minimal blunting of the right cardiophrenic sulcus (A, white arrow) and a triangular-shaped paramediastinal opacity (A, red arrow) that simulates RLL collapse. Note that the hilum is not descended. The lateral view shows blurring of the left hemidiaphragm (B, arrow) with no typical signs of pleural fluid.

Fig. 5

Coronal CT depicts a large pleural effusion, which rises higher on the medial side (C, arrow). There are no signs of RLL disease (D).

Fig. 6

Fig. 6: atypical right effusion simulating RLL collapse in a patient with silicosis (A, arrow). Right hilum is not descended. The lateral view shows findings consistent with small bilateral effusions (B, arrows).

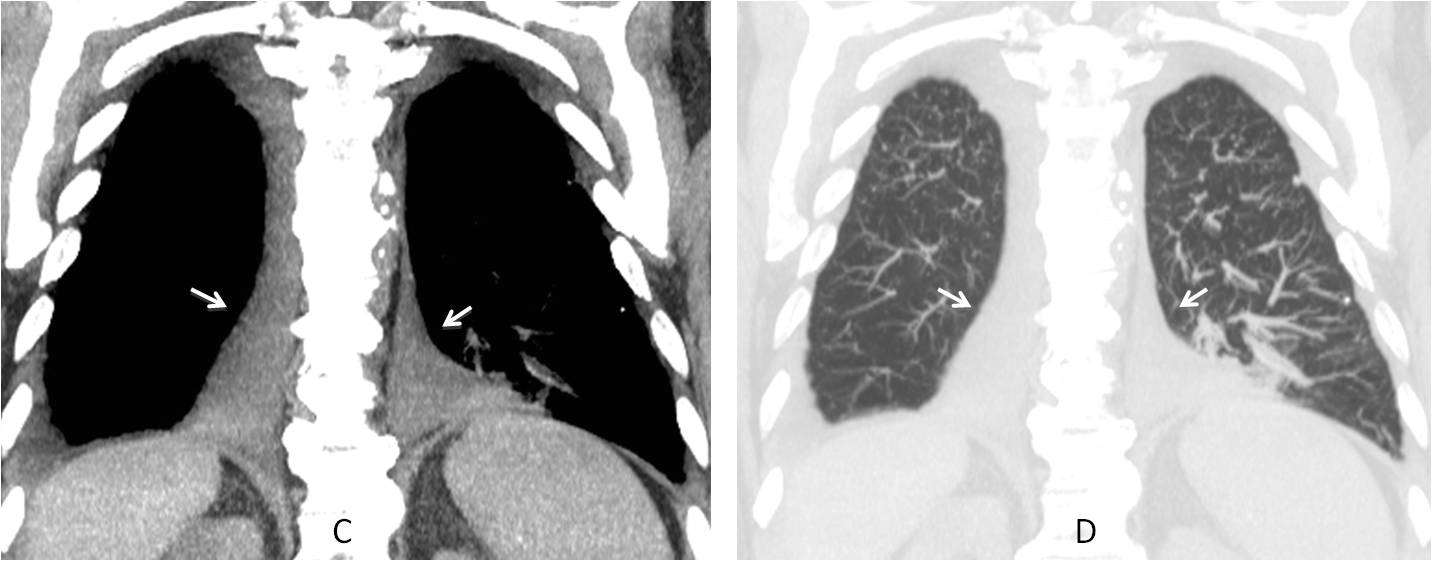

Coronal CT depicts bilateral pleural effusions, both rising higher on the paramediastinal side (C and D, arrows).

Fig. 6

Coronal CT depicts bilateral pleural effusions, both rising higher on the paramediastinal side (C and D, arrows).

In left pleural effusions, the fluid occasionally surrounds the heart, giving the appearance of cardiac enlargement (Figs. 7 and 8).

Fig. 7

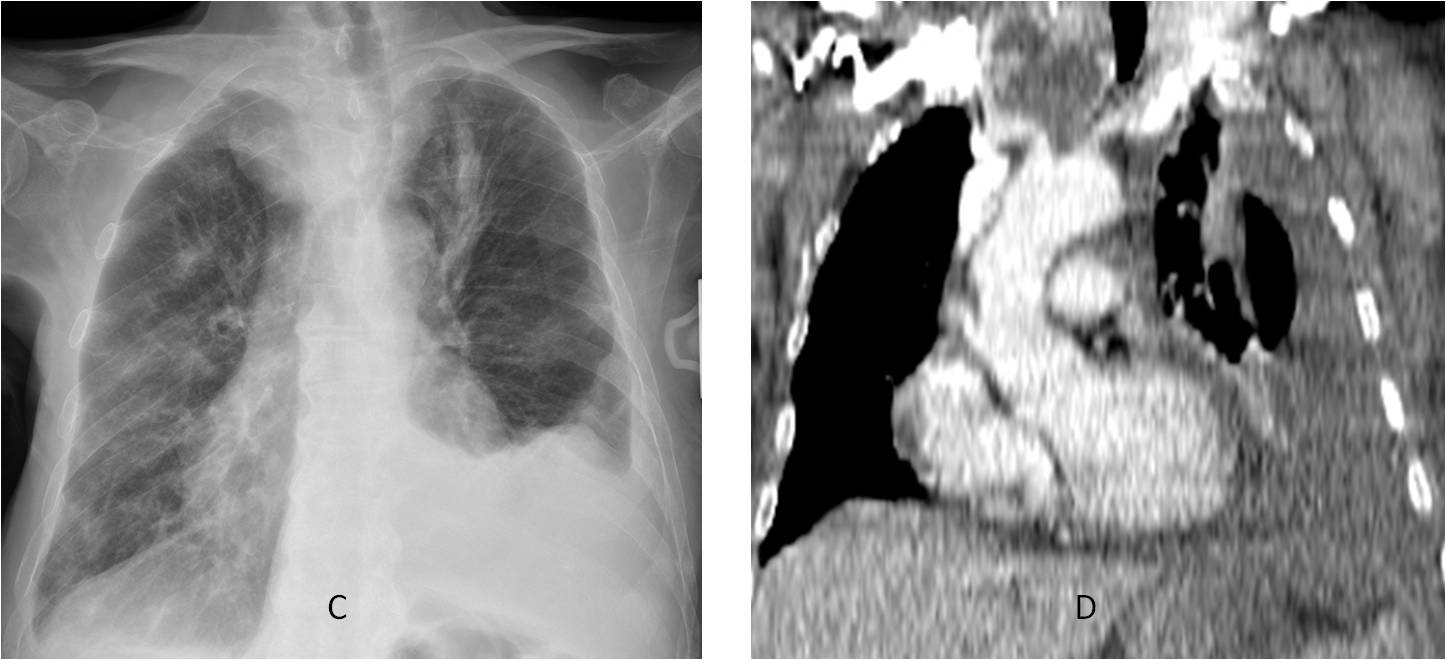

Fig. 7: patient with known goiter (A, white arrow) and apparent cardiomegaly in the PA view (A, red arrow). The lateral view shows bilateral pleural effusions, the left (B, white arrow) larger than the right (B, red arrow).

After partial removal of the fluid, the heart is better seen and appears normal in size (C), as is confirmed on the coronal CT image (D). This is a good example of left pleural effusion mimicking cardiomegaly.

Fig. 7

Fig. 8

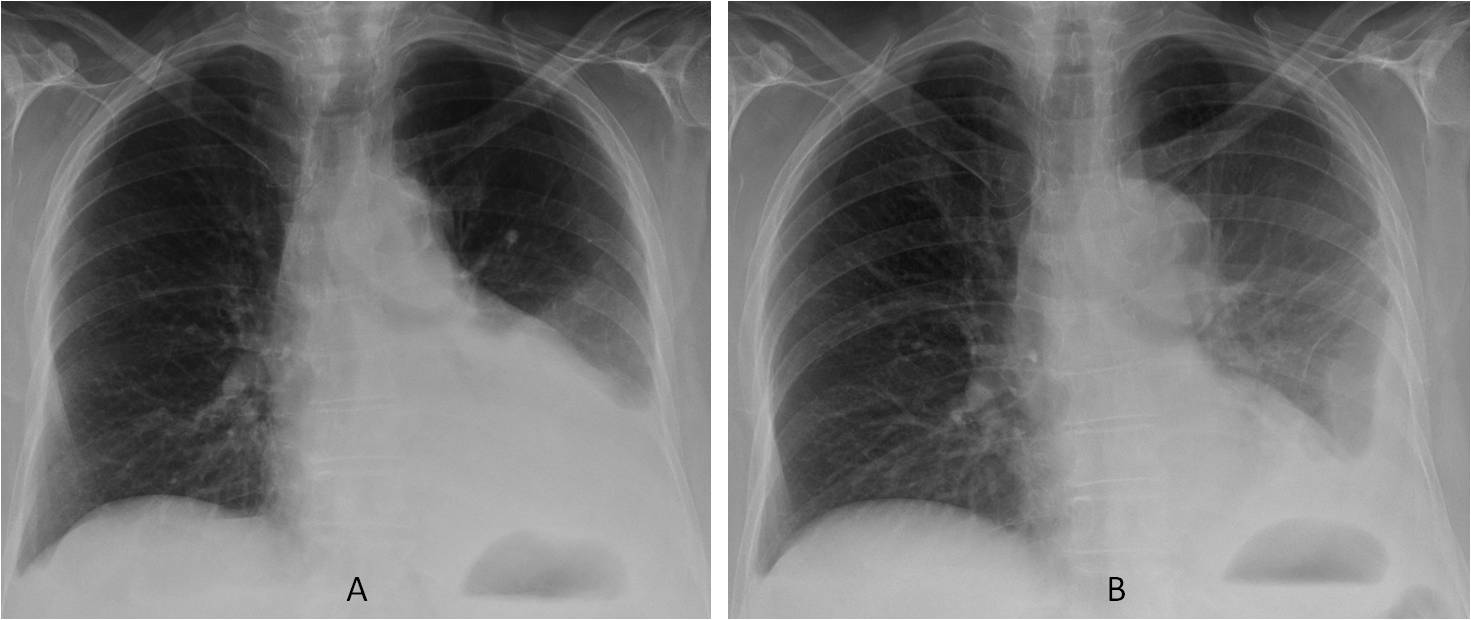

Fig. 8 (above): patient with left pleural effusion and apparent cardiomegaly. The effusion is obvious and the heart seems enlarged (A). After pleural drainage, the heart appears normal in size (B, arrow).

Rarely, free fluid may locate above the major fissure instead of gravitating to the most dependant part of the hemithorax. I have seen two such cases and don’t have the foggiest idea of why this happens. Placing the patient in decubitus position clarifies the diagnosis (Figs. 9 and 10).

Fig. 9

Fig. 9. Upright PA radiograph showing an abnormal triangular shadow (A, arrow) that may be mistaken for a pneumopericardium. The lateral decubitus view shows that the triangular shadow represents free pleural fluid (B, arrow).

Fig. 10

Fig. 10. Patient with neurofibromatosis and hydropneumothorax. The pleural fluid has collected above the right major fissure (A, white arrow), with the air-fluid level on top (A, red arrow). No fluid is seen in the costophrenic sulcus. Axial CT confirms the presence of free fluid and a pneumothorax (B, arrow). Note multiple bullae.

Follow Dr.Pepe’s Advice:

1. Subpulmonary fluid is the most common atypical presentation of free effusion. It appears as an apparently elevated and dense hemidiaphragm.

2. Paramediastinal fluid give the appearance of a reverse meniscus. It should not be confused with lower lobe collapse (hilum not descended).

3. Left pleural fluid surrounding the heart may simulate cardiomegaly.

Probably no.3

If is second picture raught lateral it should be fliped.

No. 2

2

Option 3

Hello,

there is left pleural effusion. On lateral view left hila is enlarged – mayby mass. No mediastinal shift to left is seen – probably there is also some atelectasis on the left side.

I do not believe the left hilum is enlarged. Sorry to disagree 😉

Left lower lobe collapse.

Ans.: 3

Left pleural effusion; contour abnormality of the left cardiac border, no mass seen, ? pericardial defect.

..”.l’opacita'”ilare sx è in realtà il tronco della polmonare che nel difetto pericardico a sx, si associa a rotazione in senso orario della silhouette cardiaca….infatti non è visibile, per la rotazione l’arco aortico…..versamento pleurico…..la diagnosi però la fa la TAC….

Caro amico, you will see the TC on Friday 😉

Maybe congenital absence of the left pericardium plus left pleural effusion and linear atelectases in the left lung. Number 3.

No.4

Not this time! :-))

no 1 may be associated with collaps of LLLobe

Dear friends, this time we are all mistaken, including myself, because I thought the the patient had a mediastinal tumor. CT demonstrated only pleural effusion.

I am presenting this case to discuss how atypical presentation of free pleural fluid in the plain film may confuse you.

2