Dr. Pepe’s Diploma Casebook: Case 108 – The Wisdom of Dr. Pepe (Chapter 1) – SOLVED!

Dear Friends,

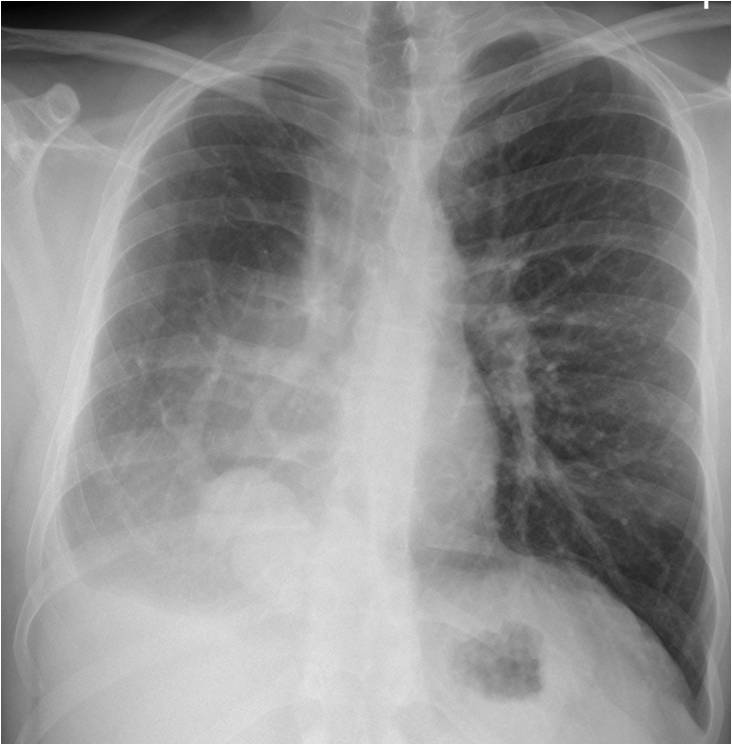

Today we’ll start the third part of The Beauty of Basic Knowledge series, entitled The Wisdom of Dr. Pepe, in which I intend to summarise my basic approach to chest interpretation. Here I am showing radiographs of a 27-year-old man with moderate cough.

As usual, check the images below, leave your thoughts in the comments section, and come back on Friday to find out the solution.

Diagnosis:

1. RML disease

2. Pleural effusion

3. RLL mass

4. None of the above

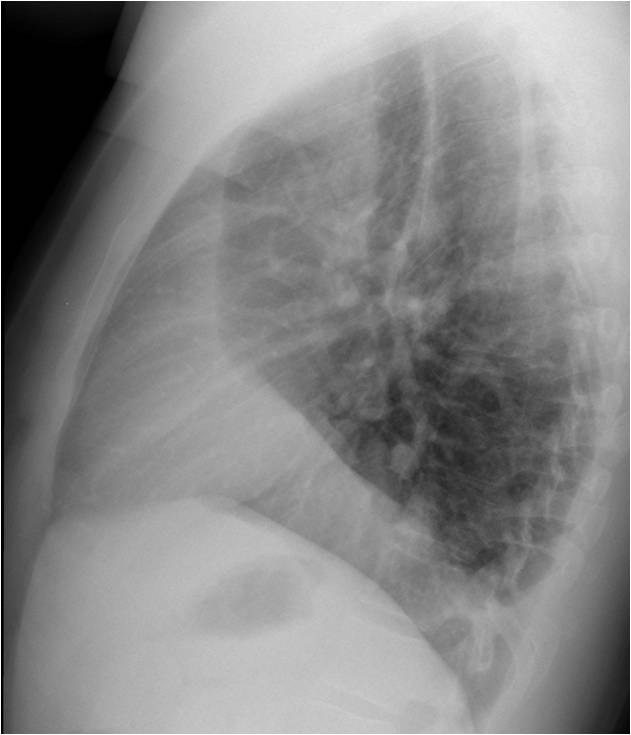

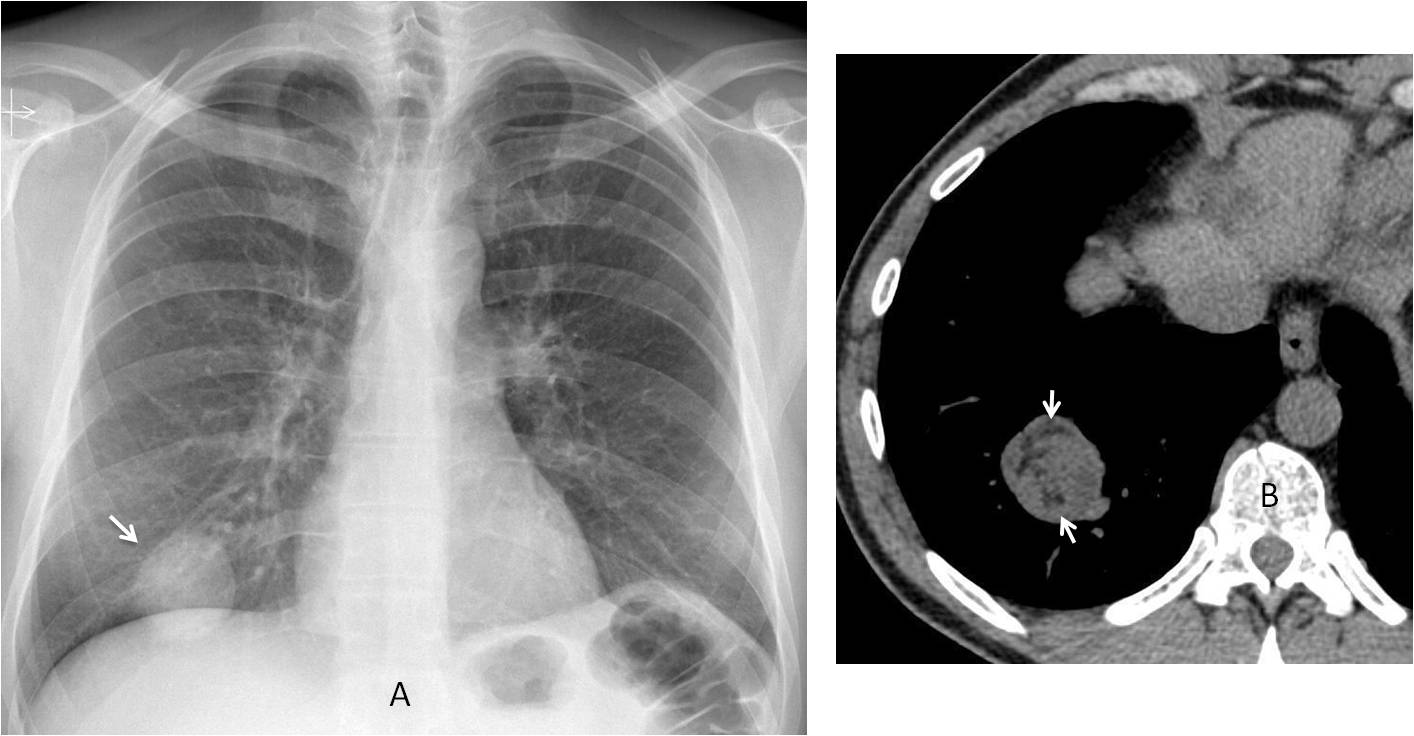

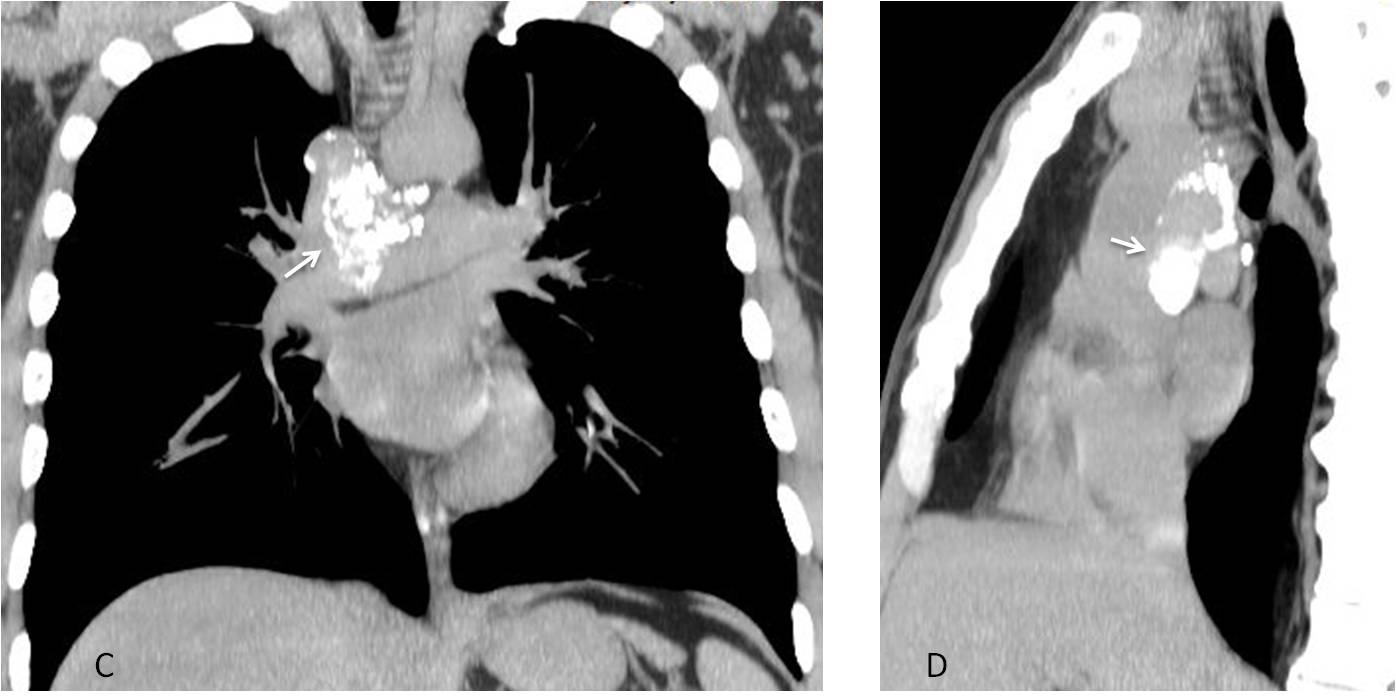

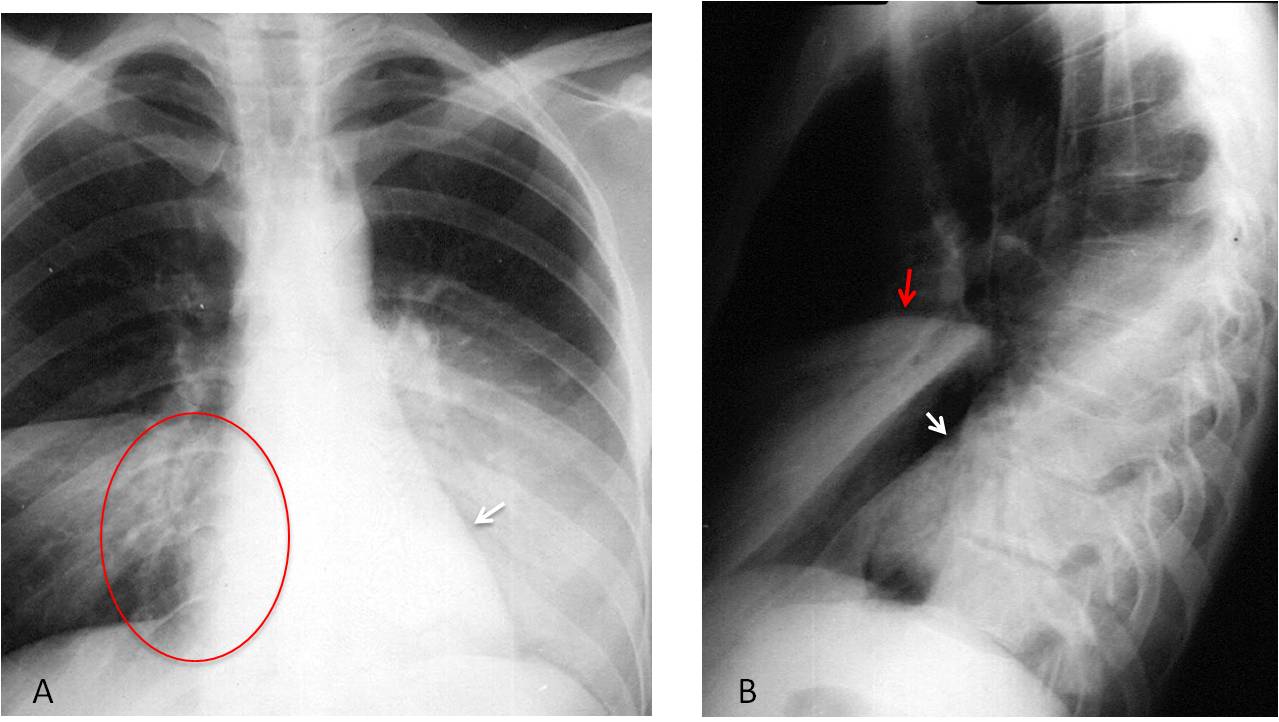

Findings: PA chest film shows a small right hemithorax. Apparently, there is pleural fluid at the right costophrenic angle (A, black arrow). The heart is displaced towards the right, with blurring of the right heart border. A vessel is running obliquely in the lower lobe (A, red arrow), and there is an adjacent rounded shadow (A, green arrow). Coronal CT confirms the anomalous vein (B, red arrow). The mass in the lower lobe is due to partial herniation of the liver (B, green arrow). Enhanced axial CT shows that the right heart border is blurred because it is in contact with the chest wall (C, circle), which has the same radiographic density (silhouette sign).

Taken together, the findings are very suggestive of congenital hypogenetic lung.

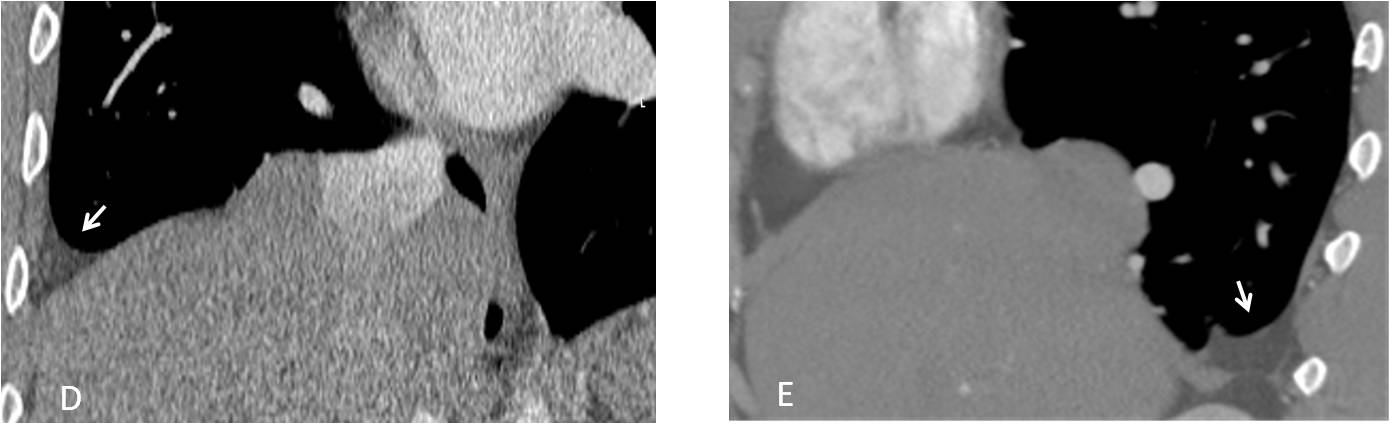

The apparent pleural effusion is due to abdominal fat (D and E, arrows) that has herniated through a posterior diaphragmatic defect. Diaphragmatic hernias are not uncommon in hypogenetic lung syndrome.

The lateral view shows a vertical retrosternal band (F, arrow), visible in many cases of hypogenetic lung. It is secondary to the decreased AP diameter of the right lung, which does not reach the anterior chest wall (G and H, red lines). Image H additionally shows the abnormal bronchial branching (H, arrow).

Final diagnosis: congenital hypogenetic lung (scimitar syndrome).

The case presented initiates the last section of our Beauty of Basic Knowledge series: The Wisdom of Dr. Pepe. In the next five chapters I intend to recapitulate the basic principles of interpreting a chest radiograph. These are summarized in the following formula, which I’ll only define as we go along to keep you guessing:

D = (bc + lv + ps + chl) e

I recommend that you look at the formula at least once a week (I don’t have to because, like Obelix, I fell into a cauldron in childhood).

In this chapter I’ll discuss the first component of the equation: basic concepts (bc), the first step in image interpretation.

When interpreting a chest radiograph, we should always remember two basic concepts, both of which proved useful in the case presented:

– Radiographic densities

– The silhouette sign

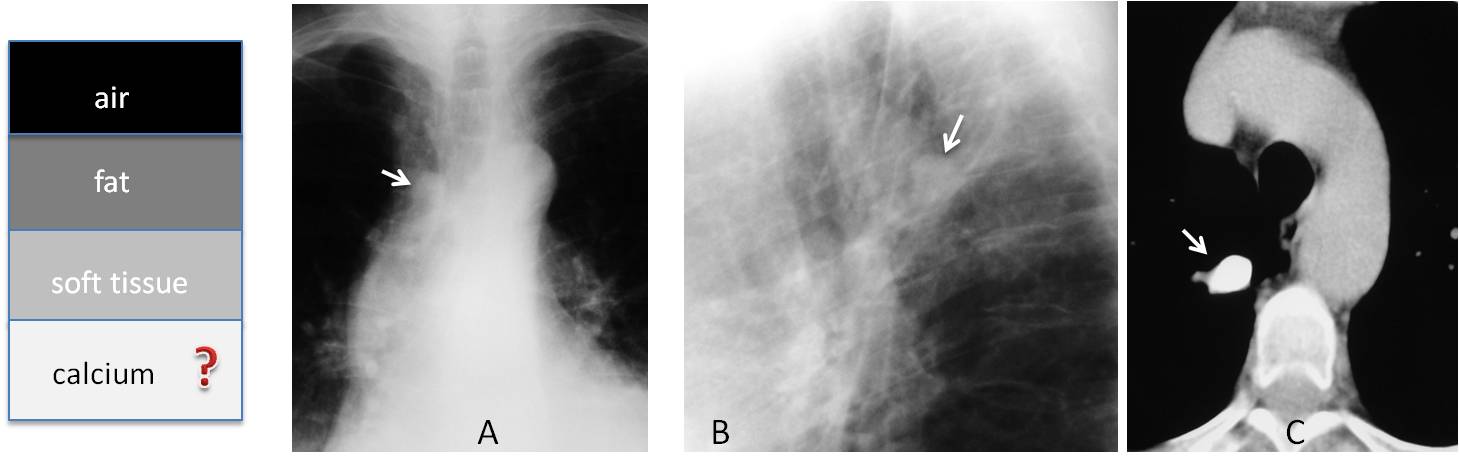

Anatomic structures and abnormal conditions are recognised in conventional radiography by their different radiographic densities, which depend on the X-ray absorption of each structure. Conventional radiography can only detect four basic densities: air, fat, soft tissue, and calcium. These cover the range from black (air) to white (bone), with two shades of grey (fat and soft tissue) in between (Fig. 1). The diagnostic process is based on the combination of these four densities.

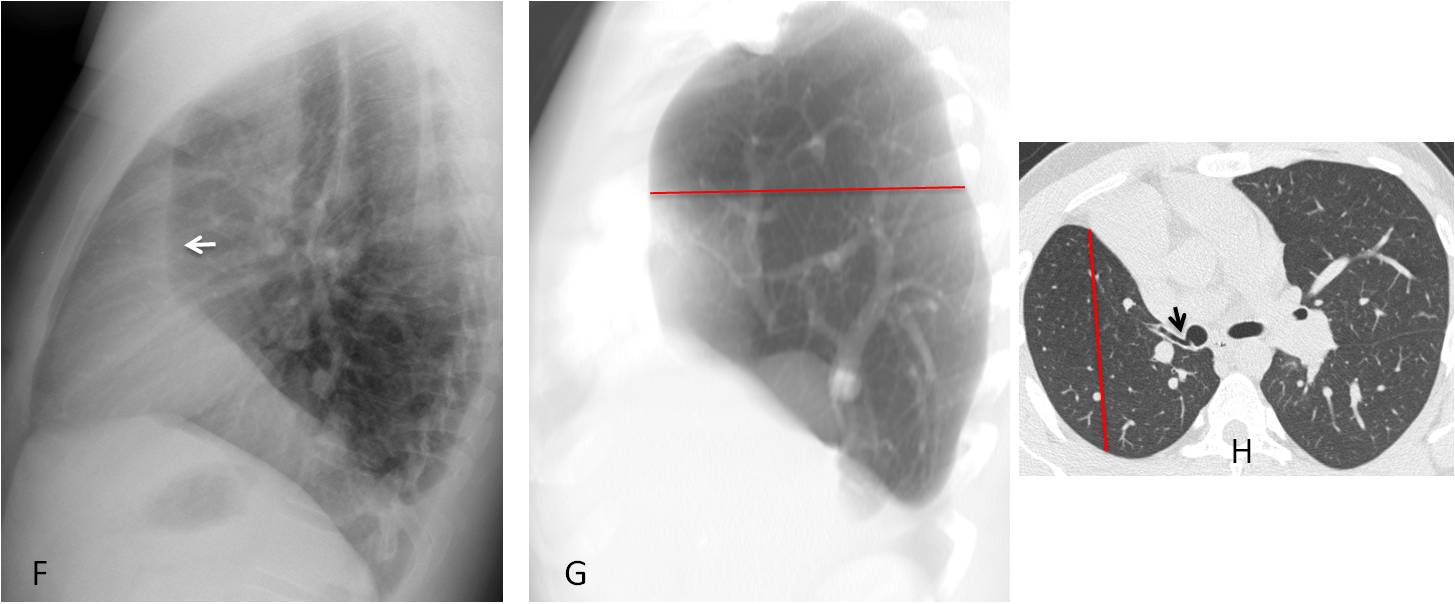

Fig. 1

Fig. 1. Depiction of the four basic radiographic densities (A). In this localised view of the shoulder, they are represented by the lung (air), the muscles of the shoulder girdle (soft tissue) and the bones (calcium). A lipoma of the shoulder (B, arrows) represents the fat.

It is important to note that fat density cannot be identified in the lungs or mediastinum and therefore, we cannot determine whether or not a finding has a fatty component. For that, we need CT (Figs. 2 and 3).

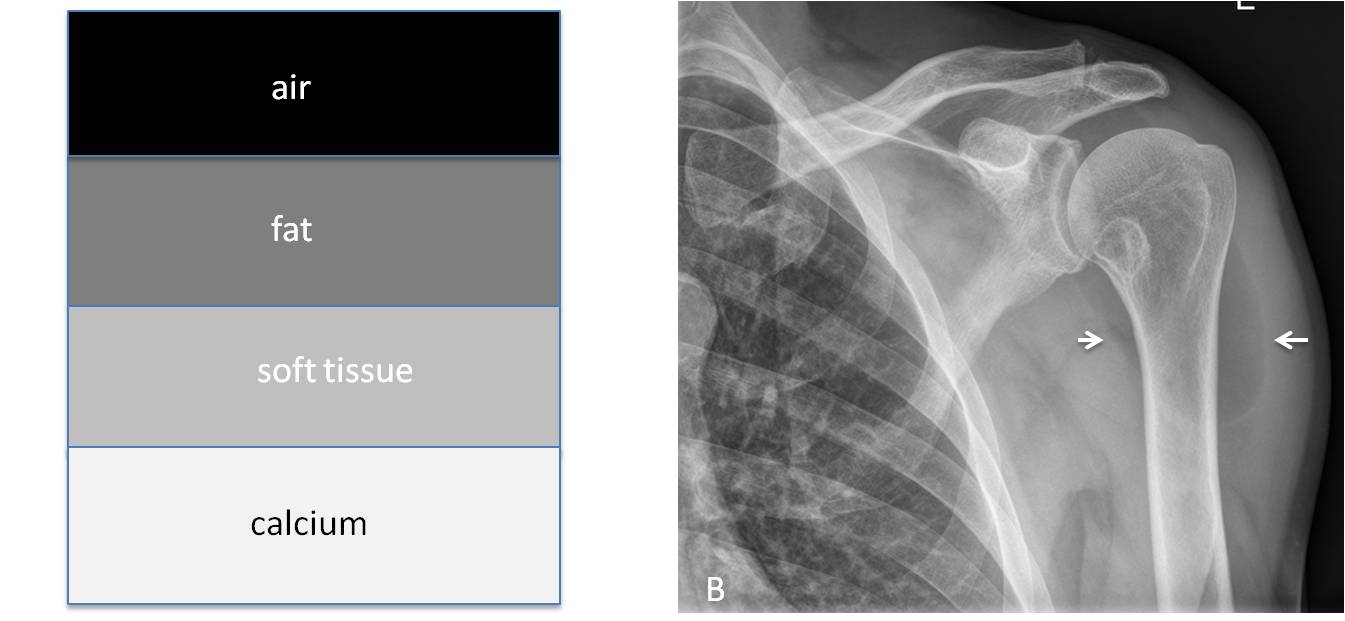

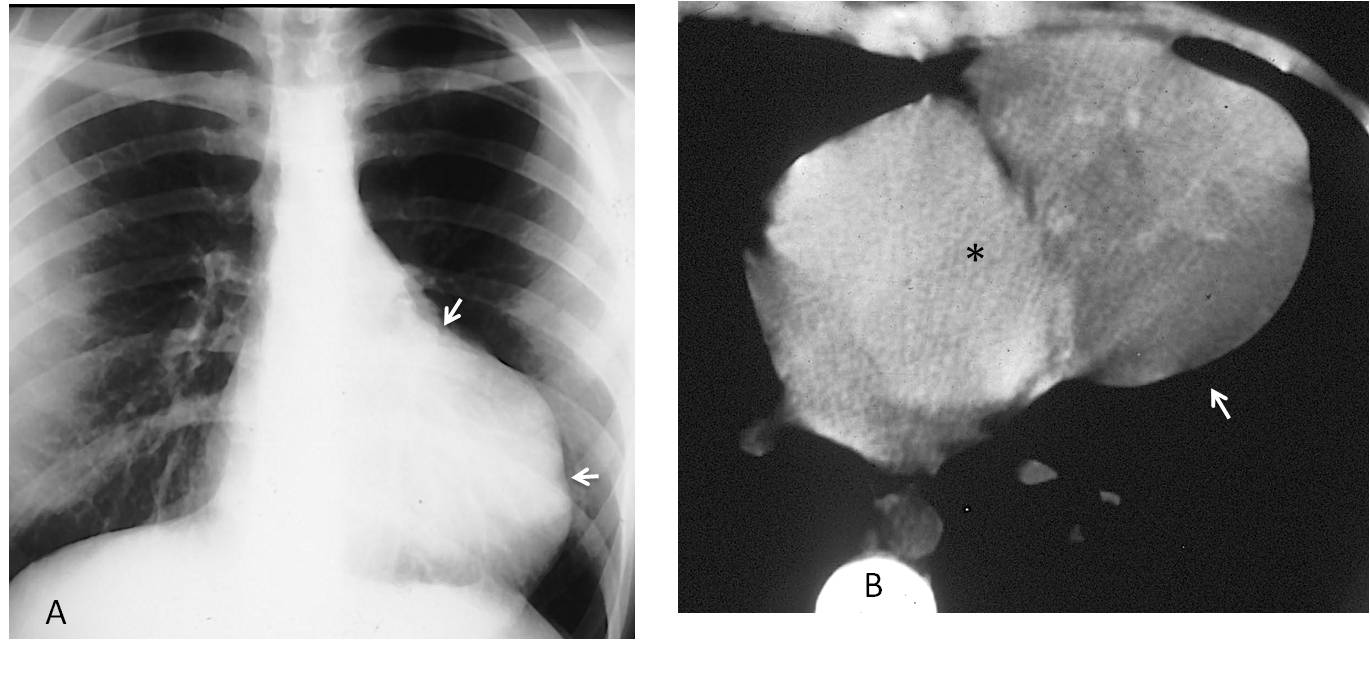

Fig. 2

Fig. 2. Anterior mediastinal mass (A, arrow) in an asymptomatic patient. The classic differential diagnosis is thymoma vs. teratoma or lymphoma. Coronal enhanced CT shows that the lesion corresponds to mediastinal fat or, less likely, a lipoma (B, arrow).

Fig. 3

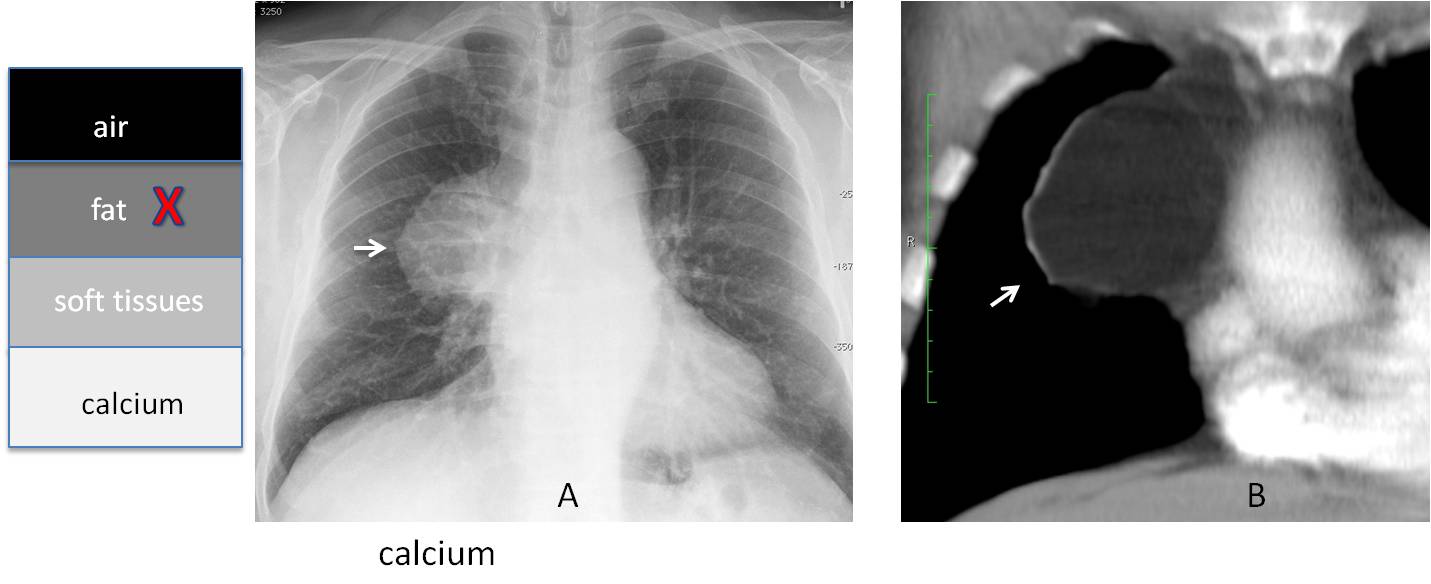

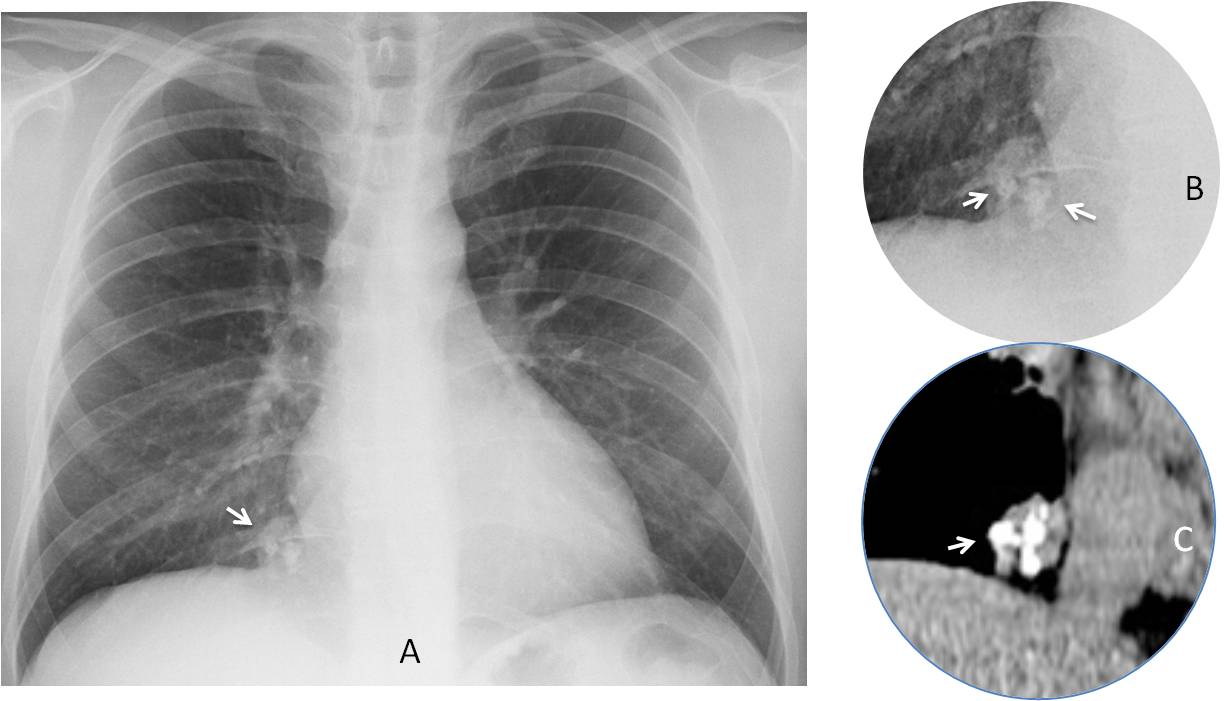

Fig. 3. 39-year-old asymptomatic man, with a nodule of uniform density in the RLL (A, arrow). Axial CT shows numerous areas of fat within the nodule (B, arrows) that were not visible in the plain film. Diagnosis: hamartoma.

It is also important to note that the high Kv now used for chest radiography tends to “burn” calcium. Therefore, calcified lesions in lungs or mediastinum may not be seen as such. This is relevant because identifying calcium is important in the diagnostic process (Fig. 4). The pragmatic approach would be: If we see calcium, OK, but if we don’t see it, we need CT to confirm or exclude it (Figs. 5 and 6).

Fig. 4

Fig. 4. Preoperative chest film shows a rounded opacity at the right cardiophrenic angle (A, arrow). There are popcorn calcifications inside, better seen in the cone down view (B, arrows), and confirmed with CT (C, arrow). Diagnosis: hamartoma.

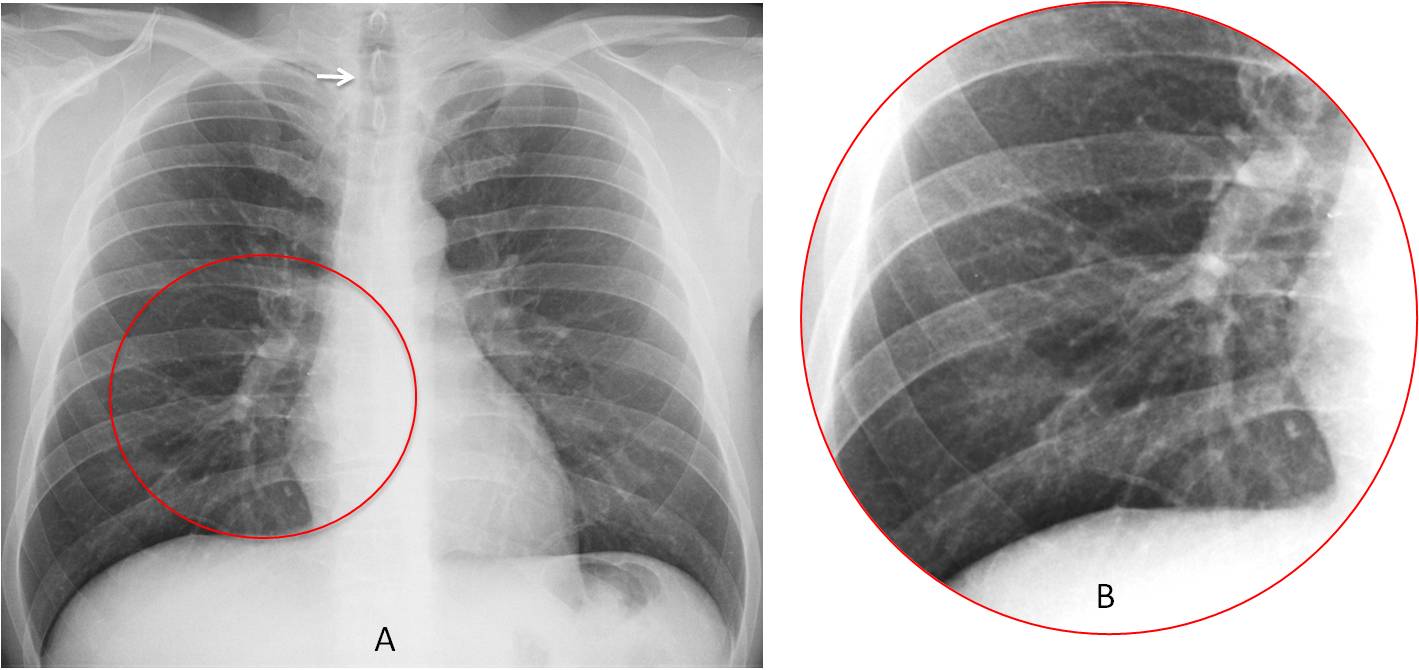

Fig. 5. 58-year-old man with an apparently non-calcified nodule discovered in the PA and lateral chest radiographs (A and B, arrows). Axial CT demonstrates a heavily calcified granuloma (C, arrow).

Fig. 6

Fig. 6. 47-year-old man with vague chest complaints. Chest radiographs (A and B) appear normal.

Coronal and sagittal unenhanced CT images show marked amorphous calcifications in the middle mediastinum (C and D, arrows), not visible in the plain film. The patient had a history of TB, and calcified lymph nodes were suspected. Unproven.

Fig. 6

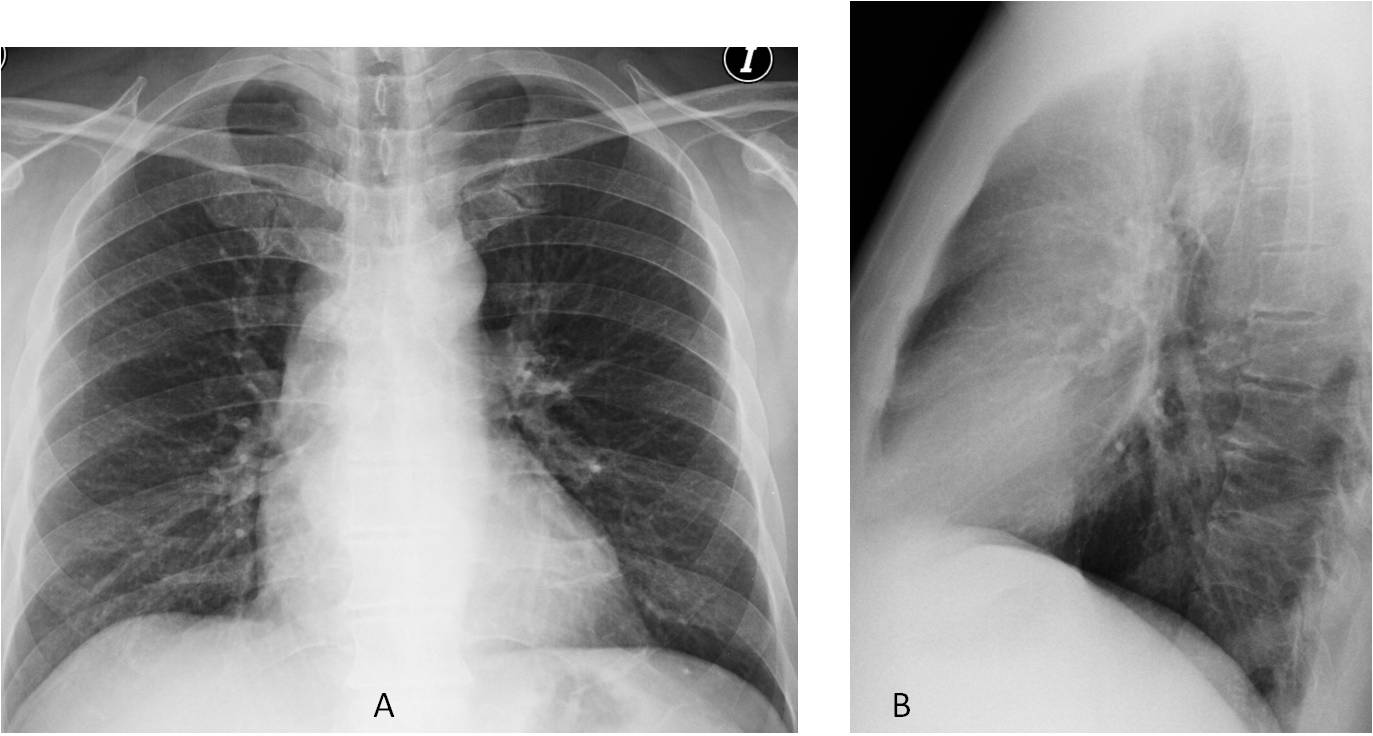

The silhouette sign was described initially by Dr. Felson as a way of determining the location of lung disease. He stated that an intrathoracic lesion touching a border of the heart, aorta or diaphragm will obliterate that border. If the lesion is not in contact, the border will be visible (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7

Fig. 7. 25-year-old man with fever and bilateral infiltrates in the lower lungs. The right one is blurring the heart border (A, circle) and therefore should be in the RML. The left one is not blurring the heart border (A, arrow) which places it in the LLL. The lateral film confirms the location of both infiltrates (B, arrows).

Over time, the meaning of the silhouette sign has changed. It can now be considered as follows: “To identify an anatomical structure or abnormality, its radiographic density should differ from that of the surrounding tissues”. This explains why we see the pulmonary vessels projected over the black background of the lung (poor man’s angiogram) and why we cannot identify the different mediastinal structures because they all have soft-tissue density, except the trachea, which has air density (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8

Fig. 8. PA chest film shows the distribution of the hila and pulmonary vessels (A and B, circles) because they have soft tissue density on a background of pulmonary air. The trachea is visible (A, arrow) because it contains air over a background of mediastinal soft tissue density.

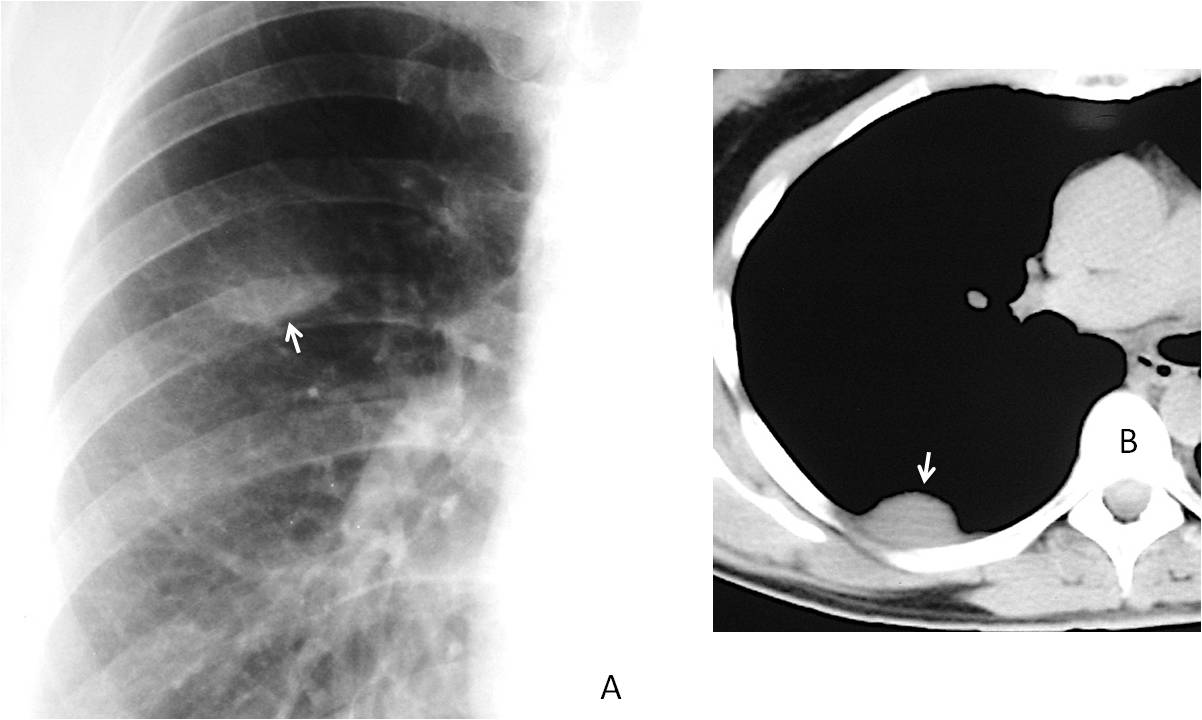

The silhouette sign is useful to detect extrapulmonary disease in the PA view. The outline of the lesion is lost where it comes into contact with the chest wall (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9

Fig. 9. Extrapulmonary lesion suspected in the PA view because only the lower border is visible (A, arrow). The blurred upper border is in contact with the chest wall. Axial CT confirms the location of the mass (B, arrow). Diagnosis: fibrous pleural tumour

Aside from localising the lesion spatially, the silhouette sign helps to suspect disease when organs take on an abnormal shape (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10

Fig. 10. 43-year-old woman with an apparently enlarged heart. The lack of cardiac symptoms and the irregular outline of the left contour suggested a mediastinal mass apposed to the heart (A, arrows). Unenhanced axial CT confirms the mass (B, arrow), which is separated from the left ventricle (asterisk) by mediastinal fat. Diagnosis: malignant thymoma.

Pulmonary lesions may be hidden when obscured by a process of similar density (eg, pleural effusion). The diagnosis is easy with CT which, aside from providing a tomographic slice, offers a wider range of densities than conventional radiography (Fig. 11).

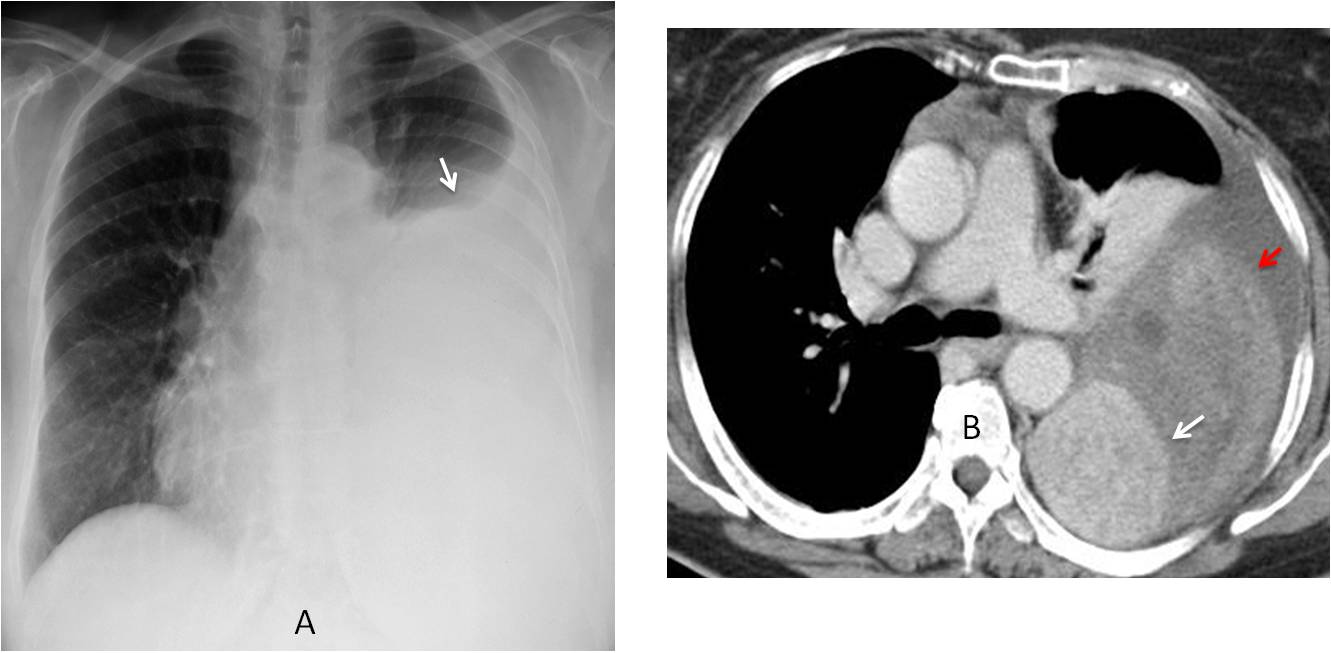

Fig. 11

Fig. 11. 47-year-old woman with chest pain. PA chest radiograph shows a large left pleural effusion (A, arrow) of unknown etiology. Enhanced axial CT depicts a pleural mass (B, white arrow) which was hidden by the pleural fluid. In addition, there are areas of increased density in the fluid caused by bleeding (B, red arrow). Diagnosis: fibrous pleural tumour.

A negative silhouette sign occurs when we expect a contour to be blurred and instead, it is clearly seen. When this happens, it may be valuable clue to discovering disease (Fig. 12).

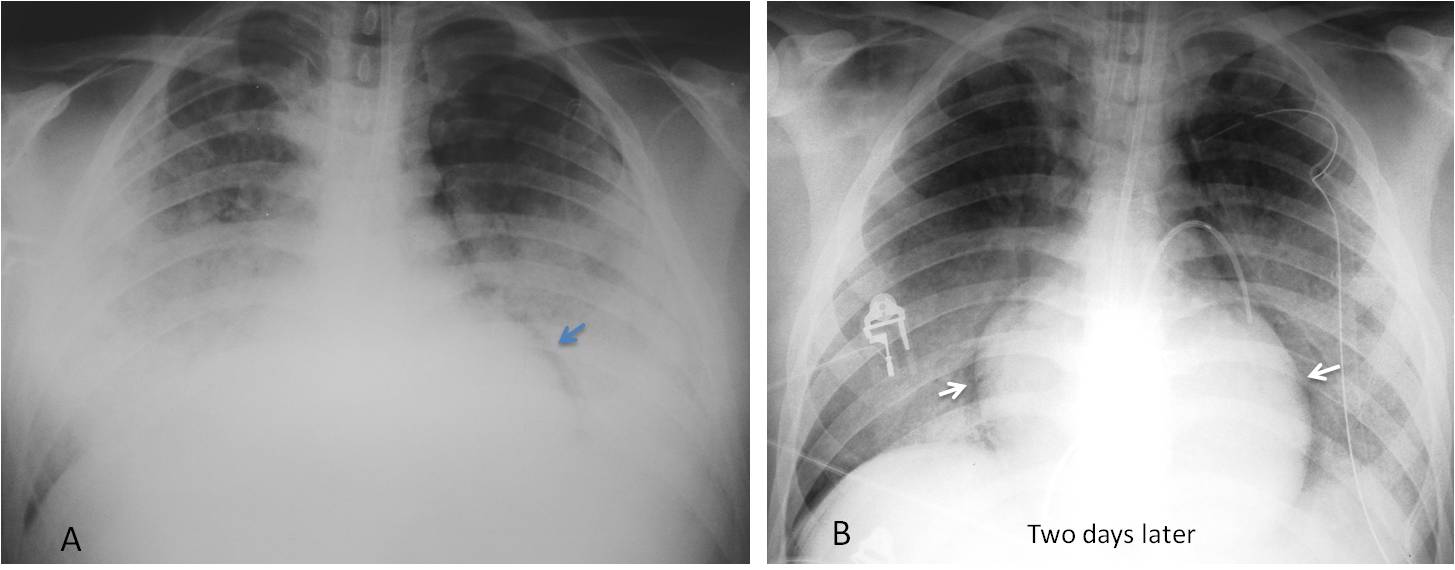

Fig. 12

Fig. 12. 53-year-old woman with ARDS. The initial supine film (A) shows bilateral pulmonary infiltrates that obscure the heart border. A radiograph two days later shows that the heart border is well defined (B, arrows) despite the persistent pulmonary infiltrates. This negative silhouette sign can be explained by pleural air surrounding the heart, rendering its outline visible. This finding was barely visible in the initial film (A, arrow). Diagnosis: bilateral pneumothorax in ARDS.

Dr. Pepe’s first commandment:

1. Thou shalt always know the basics:

- Radiographic densities

- Silhouette sign

Good moorning!

There is a loss of volume of the right hemithorax. The right cardiac border and the ipsilateral are bad defined.

There is an increased vascularization proyected over the lower lobe with an increased tubular density. In the lateral view we can see a line typical of right hipoplasia.

A pulmonary hipoplasia with a cimitar syndrome is a good option.

Hello,

MK has a point…

I think the mass in the lower pole on right could represent extralobar sequestration.

Vascularization seems to indicate PAPVR

So: mixed congenital lesion combined of rgiht lung hypoplasia/ scimitar syndrome with pulmoary sequestration and PAPVR (bronchial atresia cannot be excluded)

Can’t wait to see the answer.

Only three more days…

Hi,

absence of the right atrial and right diaphragmiatic outline/border on the PA view, with crescent sign.

lobulated structure over the right cardiophrenic angle on AP view that seems to be located over the anterior costophrenic recess on the lateral view.

impression: right lower and middle lobe collapse with pleural effusion and morgagni hernia.

thanks

Good imaginative answer. Wouldn’t you expect a triangular hilar-based shadow with lobar collapse?

1. small right lung

2. rightward dextroposition of the heart

3. tubular/serpiginous dilated opacity running from right hilum to below the diaphragm

Dx – Scimitar syndrome

There is homogeneous opacity over the lower right hemithorax silhouetting the right hemidiaphragm and right hilum and a rising fluid level due to pleural effusion. Loss of volume of the hemithorax as indicated by the tracheomediastinal shift to the left. Hence collapse or agenesis to be considered. A Lobulated opacity in the right Cardiophrenic angle and abnormal vessel seen over the right lower lung suggests scimitar or venolobar syndrome.The mass may represent sequestration but I am unable to localize it in lateral view. Could this be loculated effusion.

Remember what Dr. Pepe says: any opacity adjacent to the diaphragm maycome from below

Agenesia del pericardio

V. lenoci , 12

Is this an address?

…si…

……magico “blugrana”….avevo previsto il risultato di Madrid ( il Barca ” sbanca ilReal)….proviamo a centrare la diagnosi…..a me sembra una patologia congenita, con ipoplasia del lobo inferiore, su base vascolare…..non vedo l’ilo vascolare di dx e l’opacita mi sembra di natura vascolare….pertanto anomalo ritorno venoso parziale , che si associa ad ipoplasia polmonare…..

Scimitar syndrome 9hypogenetic lung syndrome) with pleural effusion

In this case, the clue to the diagnosis lie in identifying the scimitar vein, which is a telltale sign of hypogenetic lung.

Congratulations to all of you who made the diagnosis, led by MK, who was the first.