Dr. Pepe’s Diploma Casebook: Case 59 – SOLVED!

Dear Friends,

This is the last case of the present term. I wish you all a very happy vacation. We will meet again in September.

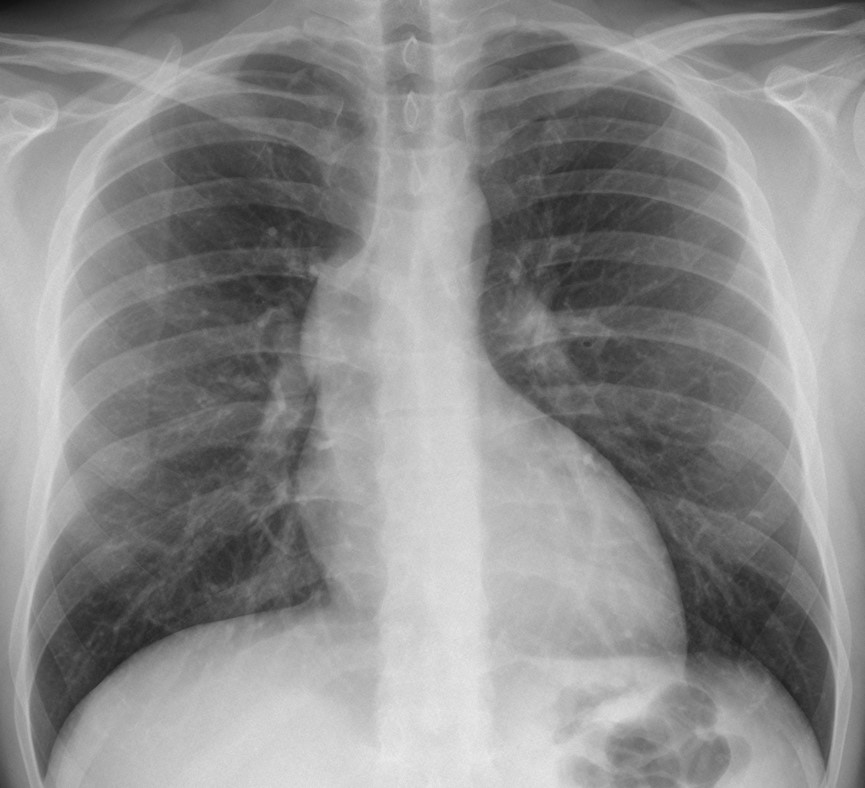

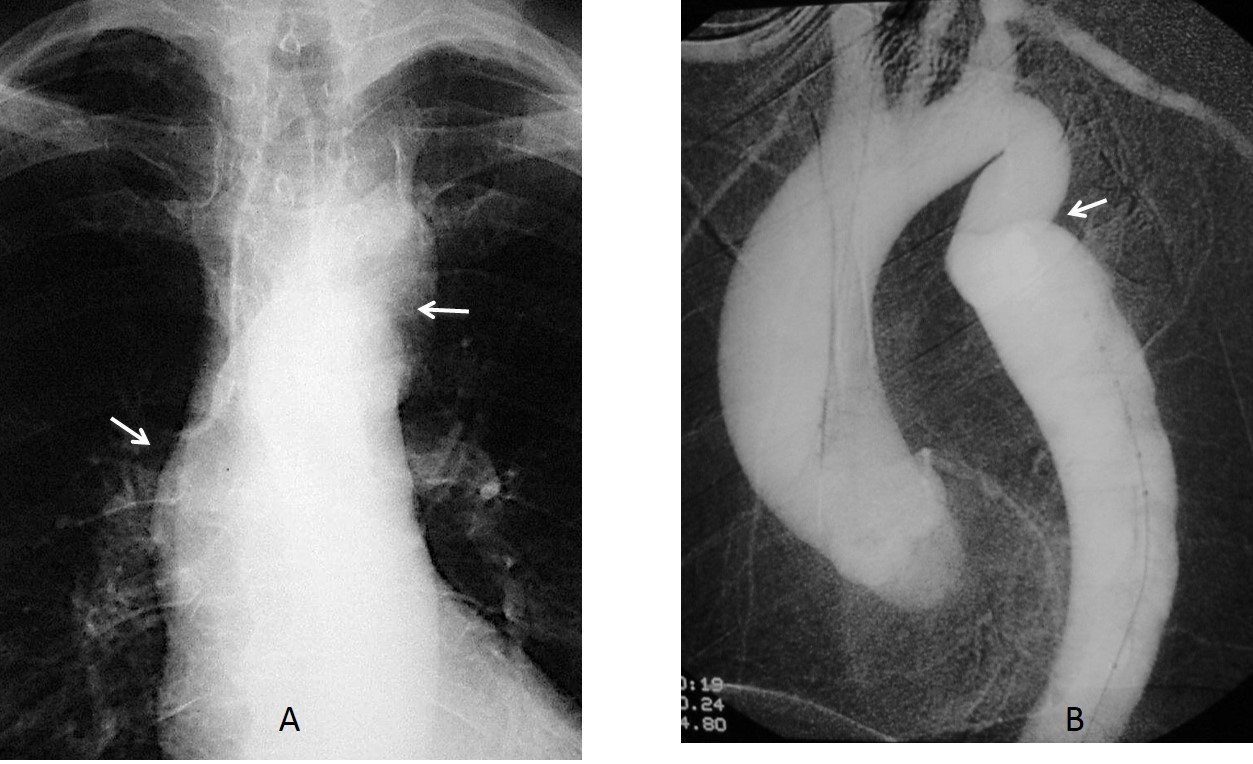

The radiographs below belong to a 31-year-old man with vague chest pain. Diagnosis:

1. Aortic dissection

2. Aortic valve stenosis

3. Ascending aorta aneurysm

4. All of the above

Leave your thoughts and diagnosis in the comments section and come back on Friday for the answer.

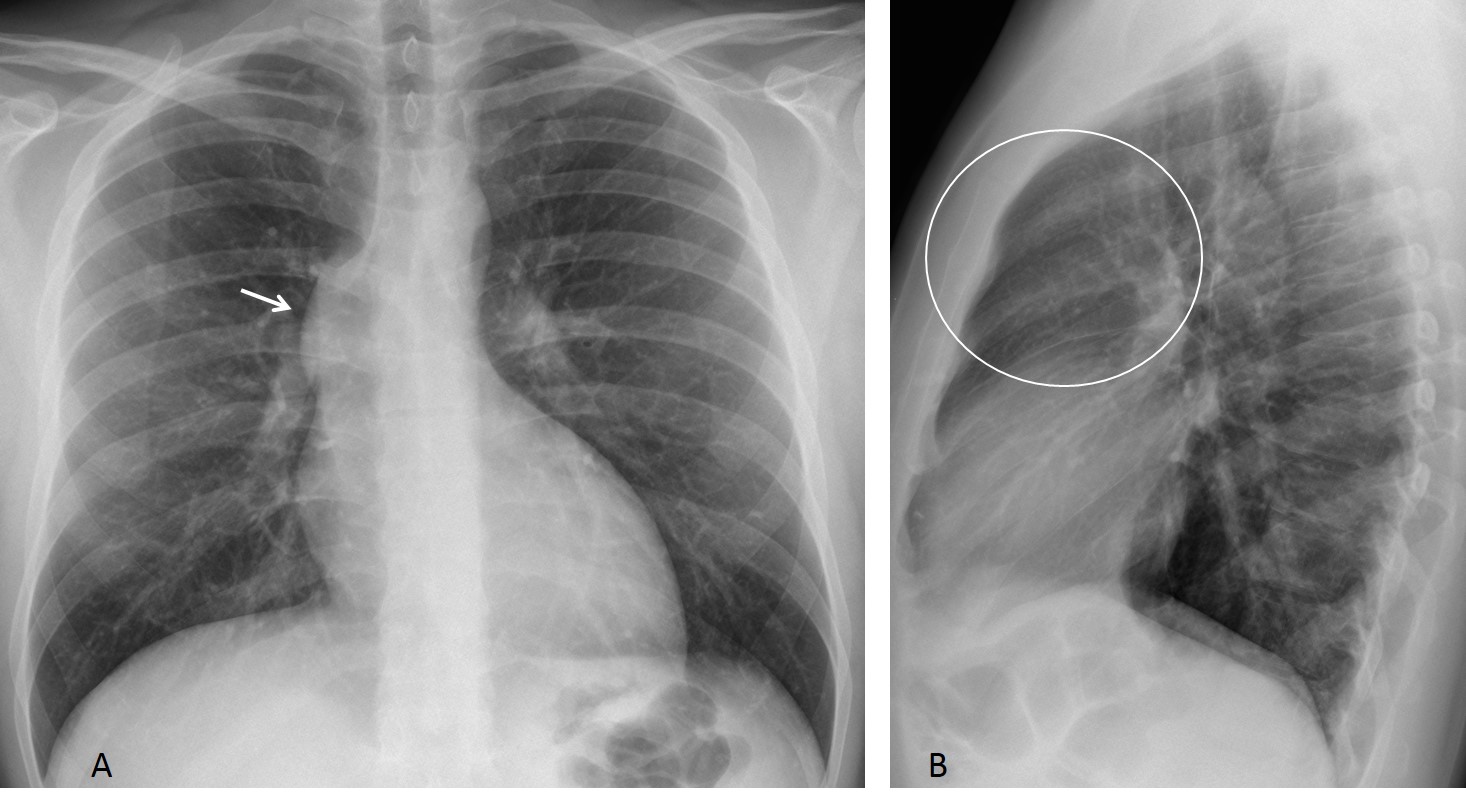

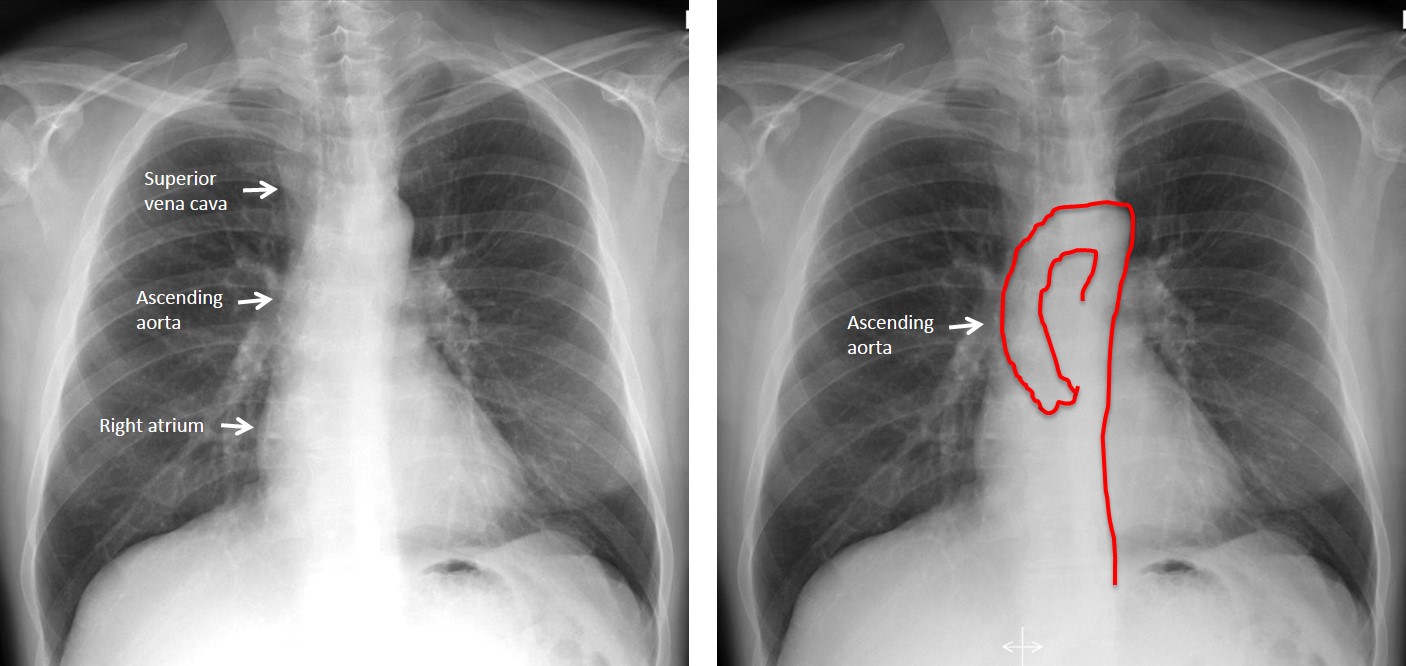

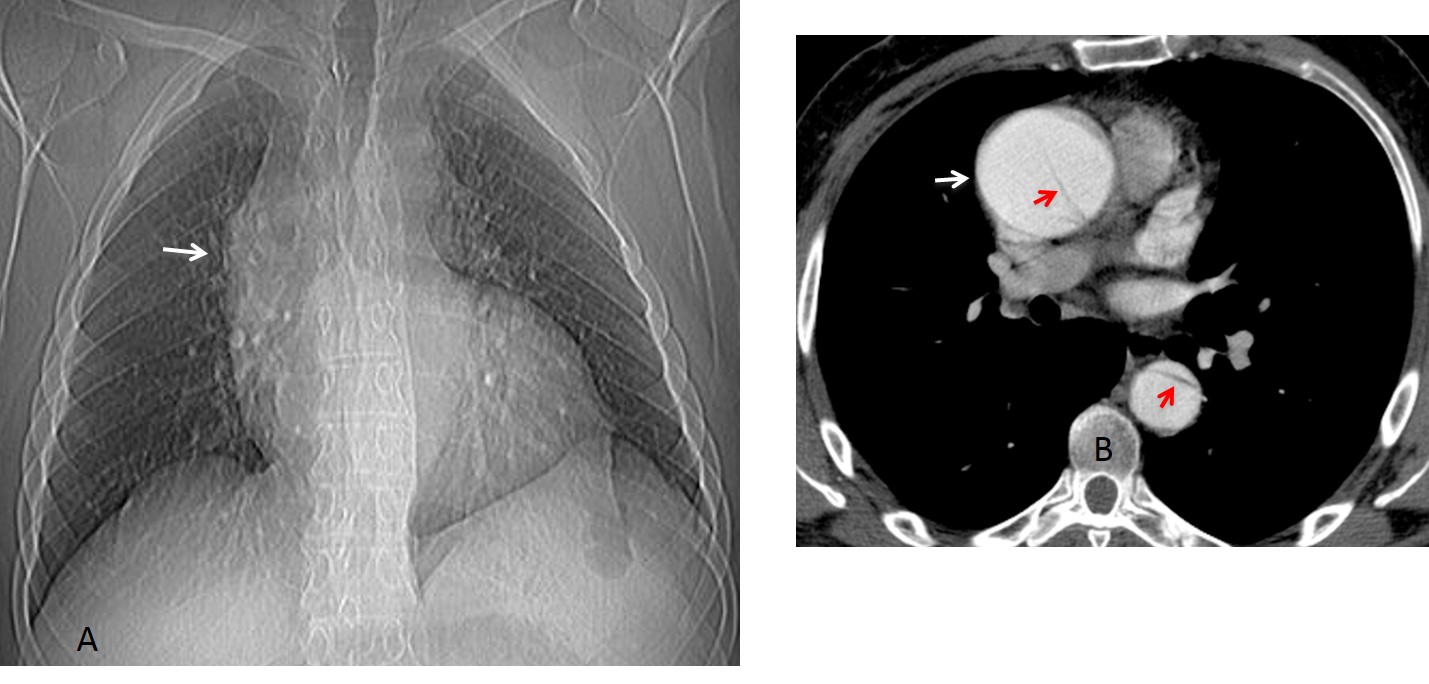

Findings: bulging of the right mediastinal contour at the level of the second segment (arrow) and haziness of the anterior clear space in the lateral view (B, circle). These findings suggest dilatation of the ascending aorta, which can occur in all three diagnoses offered. Therefore, the correct answer is: all of the above.

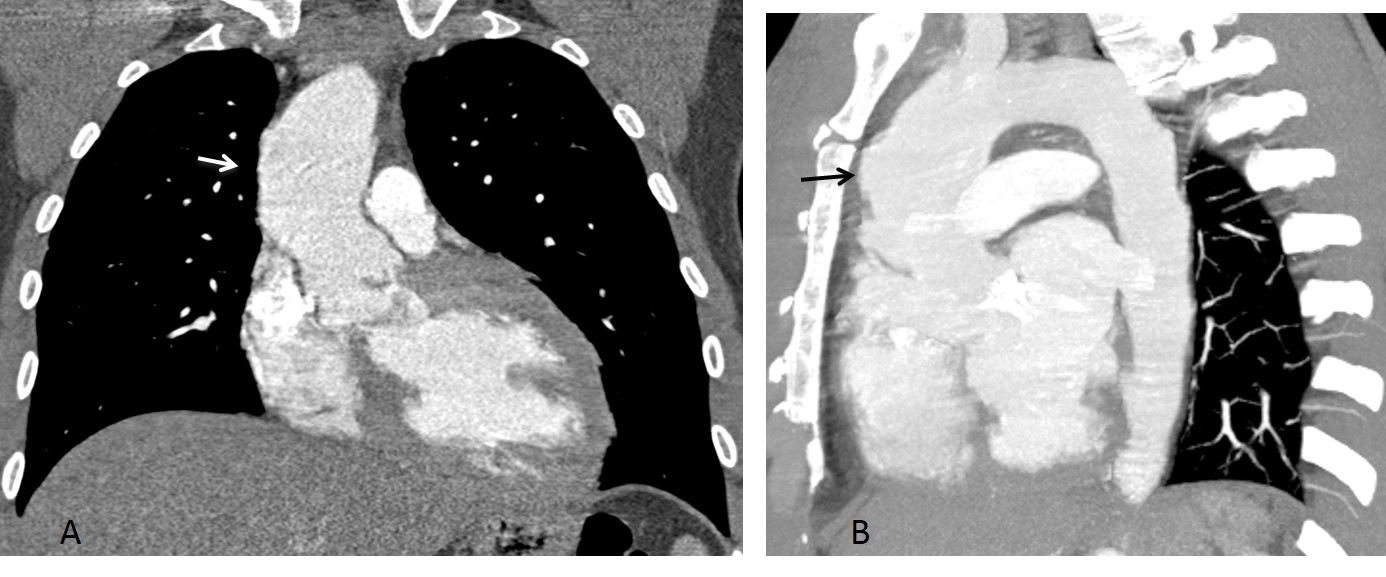

Clinical and ultrasound investigation discovered a bicuspid aortic valve. Enhanced CT confirms ascending aorta dilatation (Fig.2 A,B arrows), a common finding in aortic valve stenosis.

Final diagnosis: Isolated ascending aorta dilatation, secondary to bicuspid valve.

This case is presented to discuss prominence of the middle mediastinal segment. The right mediastinal border is divided in three segments: the upper one corresponds to the superior vena cava, the middle one to the ascending aorta and the lower one to the right atrial border.

Prominence of the middle segment is usually a result of dilatation of the ascending aorta. Four conditions cause isolated ascending aorta dilatation:

- Bicuspid aortic valve

- Ascending aorta aneurysm

- Type A aortic dissection

- Aortic coarctation

These changes reflect a congenital anomaly of the region including the aortic valve, ascending aorta, and aortic arch. Each abnormality can appear alone or in combination with any of the others.

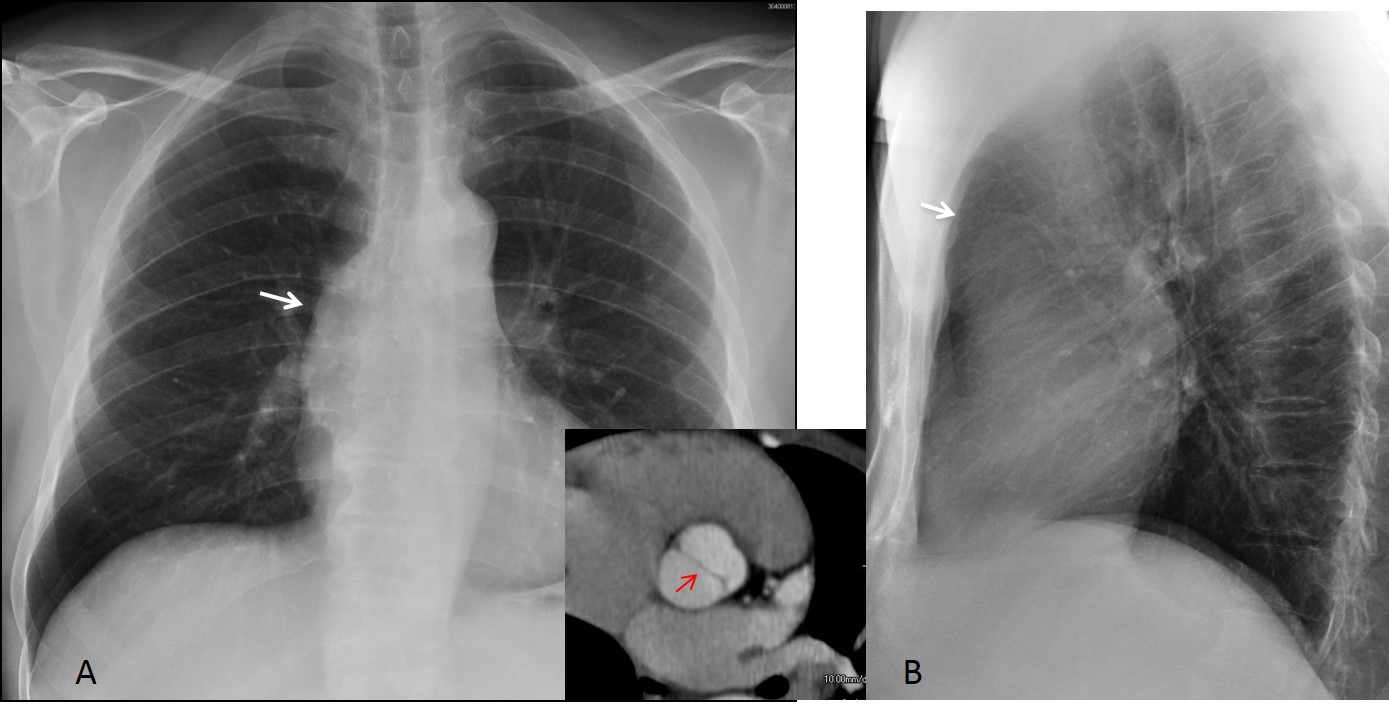

Bicuspid aortic valve causing stenosis is a common congenital malformation, occurring in about 2% of the population. The stenotic jet strikes the aortic wall and leads to dilatation, favored by the congenital weakness of the wall that is part of this condition. Patients may be symptomatic or reach advanced age without significant symptoms (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4: 66-year-old man with systemic hypertension in whom a bicuspid valve was found. PA and lateral radiographs show enlargement of the ascending aorta (A,B, arrows). Note bicuspid valve (insert, arrow).

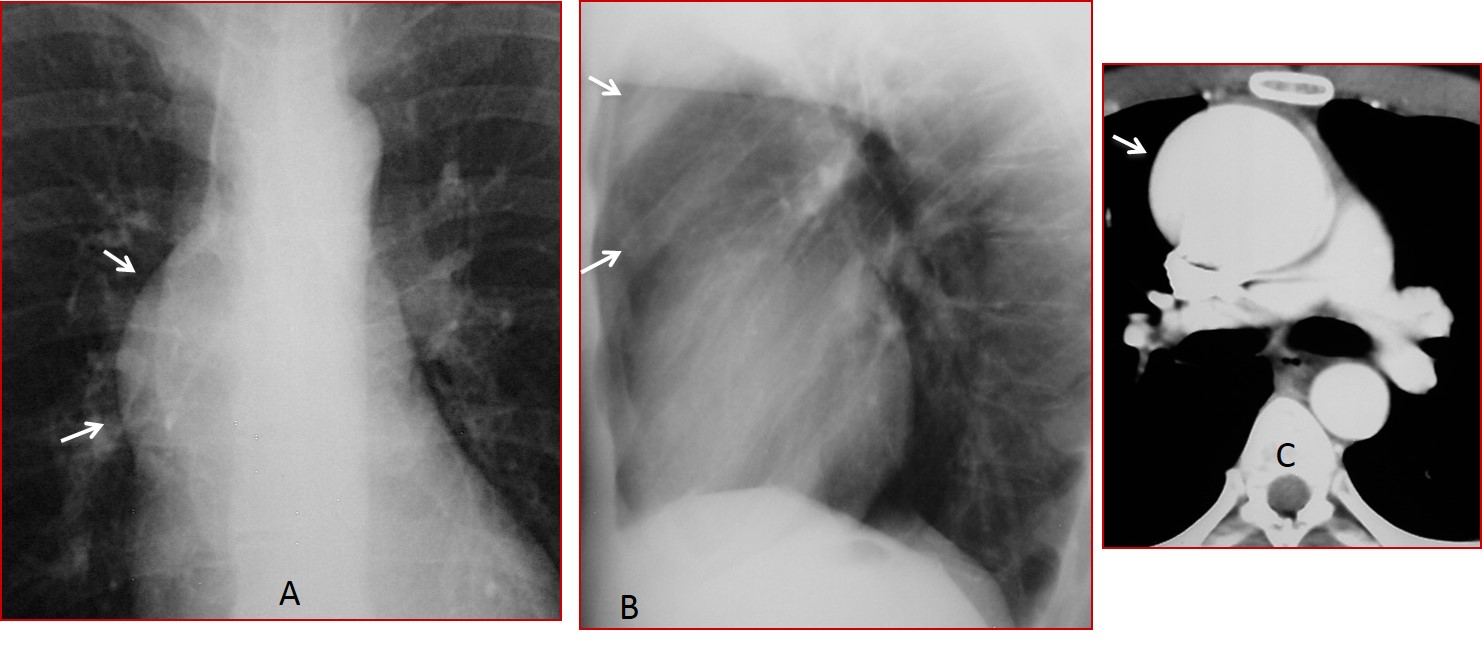

Ascending aorta aneurysms can also cause a prominent middle segment (Figs. 5 and 6). They may be arteriosclerotic or associated with connective tissue disorders. In the latter case, related findings such as skeletal changes in Marfan syndrome or joint laxity in Ehlers-Danlos may help to suggest the diagnosis.

Fig 5 (above): 18-year-old male with Marfan syndrome and aneurysm of ascending aorta. Marked prominence of the ascending aorta in the PA an lateral views (A,B, arrows). Enhanced CT confirms the aneurysm (C, arrow).

Atherosclerotic aneurysms usually occur in the descending aorta, but may also happen in the ascending aorta. In young individuals, infection or arteritis should be investigated.

Fig 6 (above): 72-year-old man with calcified aneurysm of ascending aorta. PA and lateral views show the calcified walls and the prominent ascending aorta (A,B, arrows).

Fig. 7 (above): unenhanced CT shows the aneurysm and calcification of the walls (A,B arrows). Enhanced CT confirms the diagnosis (C,D arrows).

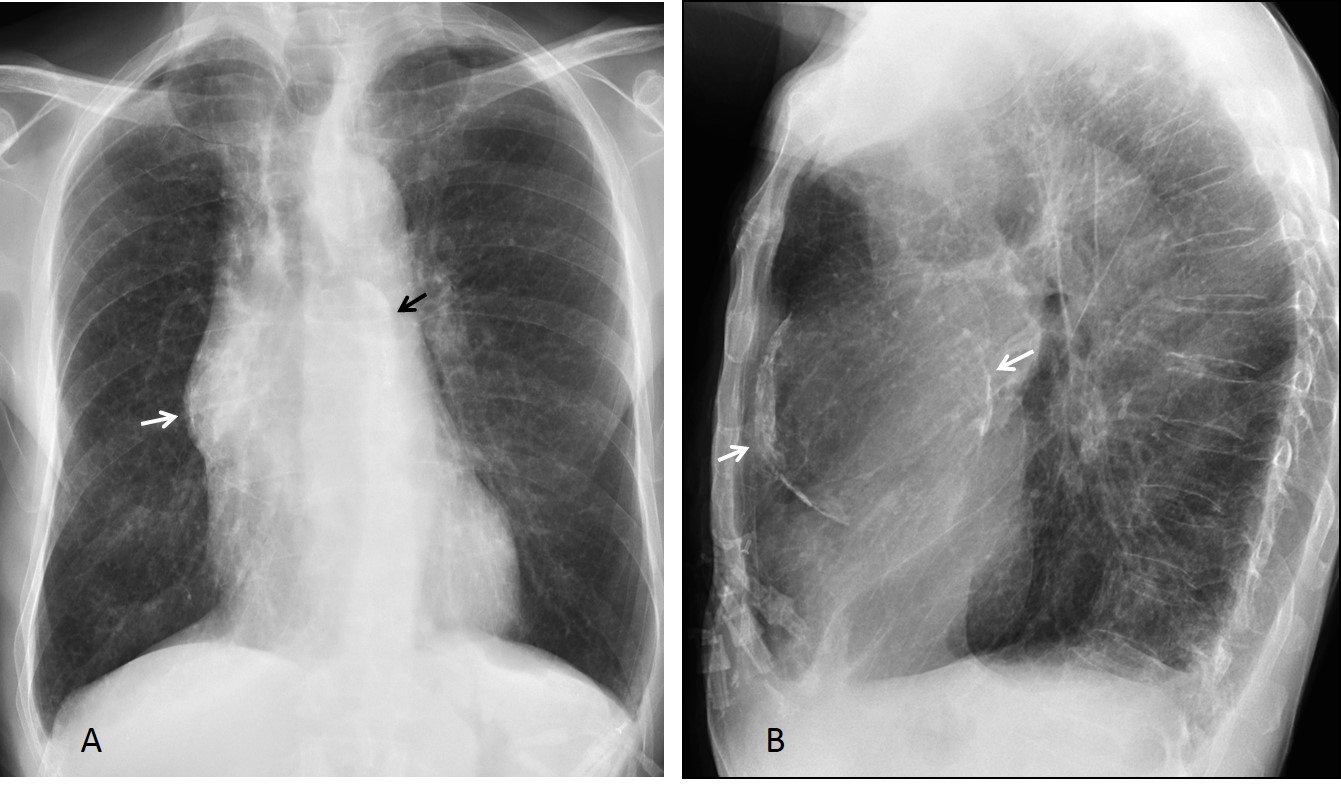

Type A dissection causes dilatation of the ascending aorta, although the chest may be normal in up to 20% of patients. This is a life-threatening condition, which explains why many patients go directly to CT, and chest radiographs are only taken after surgery (Fig. 4).

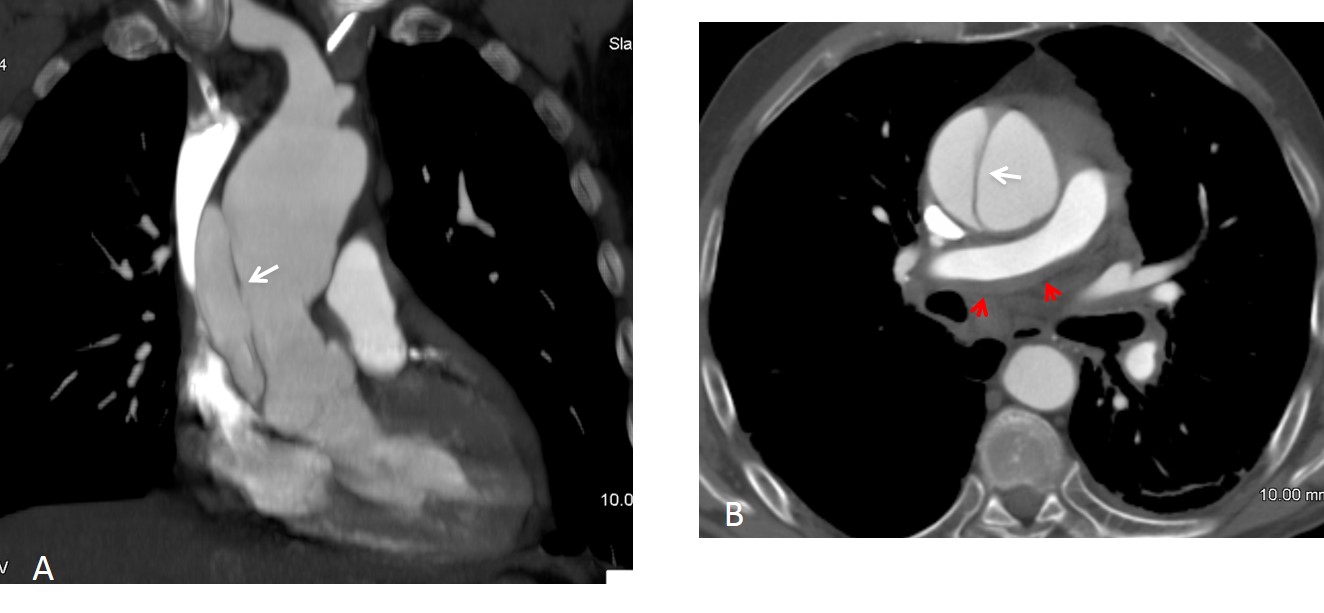

Fig 8 (above): 42-year-old man with type A aortic dissection. CT scout film shows a prominent ascending aorta (A, arrow). Enhanced CT confirms the enlarged ascending aorta (B, white arrow) and depicts the flap, which extends to the descending aorta (B, red arrows).

Among the complications of type A dissection are rupture into the pericardium or mediastinum. A rare complication of mediastinal haematoma is dissection of the pulmonary sheath, causing narrowing of the right pulmonary artery (Fig. 9)

Fig. 9 (above): 46-year-old man with type A dissection (A,B, white arrows). Blood has invaded the pulmonary sheath, causing moderate narrowing of the right pulmonary artery (B, red arrows).

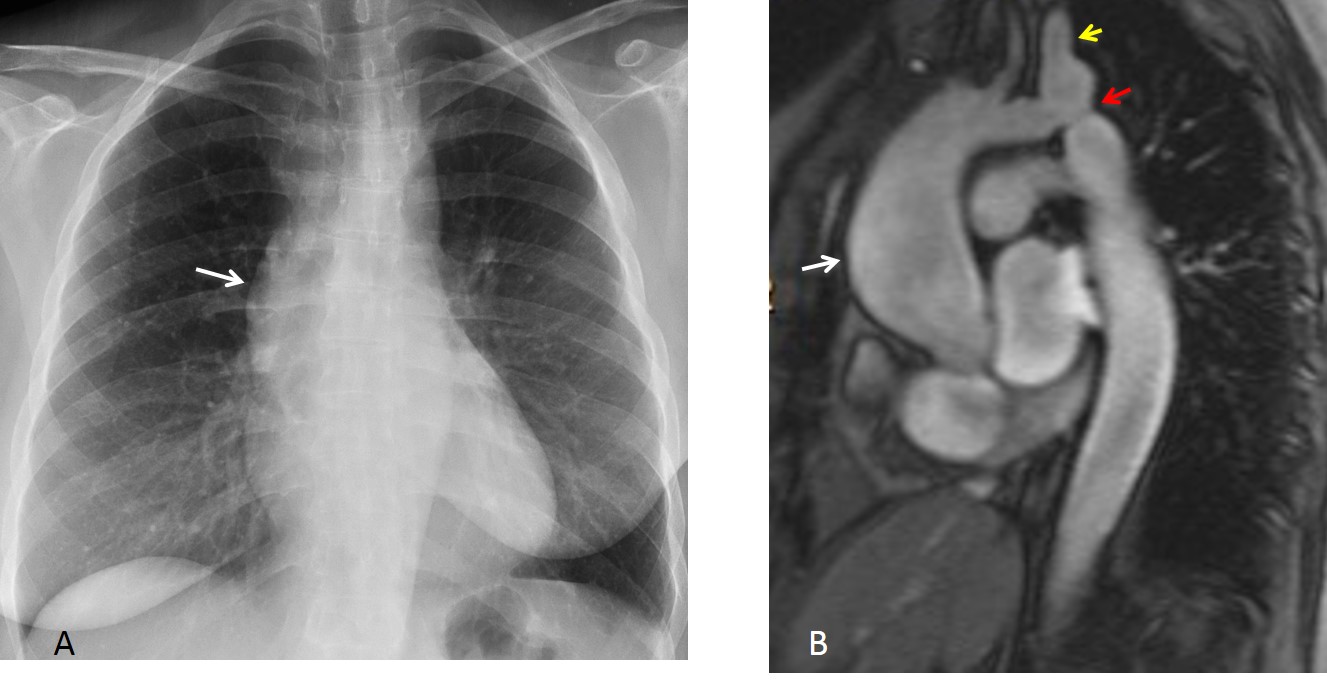

Aortic coarctation, a narrowing of the vessel at the level of the ligamentum arteriosum and distal to the left subclavian artery (Fig. 10), accounts for 7% of congenital heart diseases. Bicuspid aortic valve is seen in 22% to 42% of cases. Untreated aortic coarctation has a poor prognosis (75% mortality by 46 years of age).

Fig. 10 (above): 36-year-old woman with aortic coarctation. Prominent ascending aorta (A,B, white arrows). MRI shows the area of narrowing (B, red arrow), distal to the dilated left subclavian artery (B, yellow arrow).

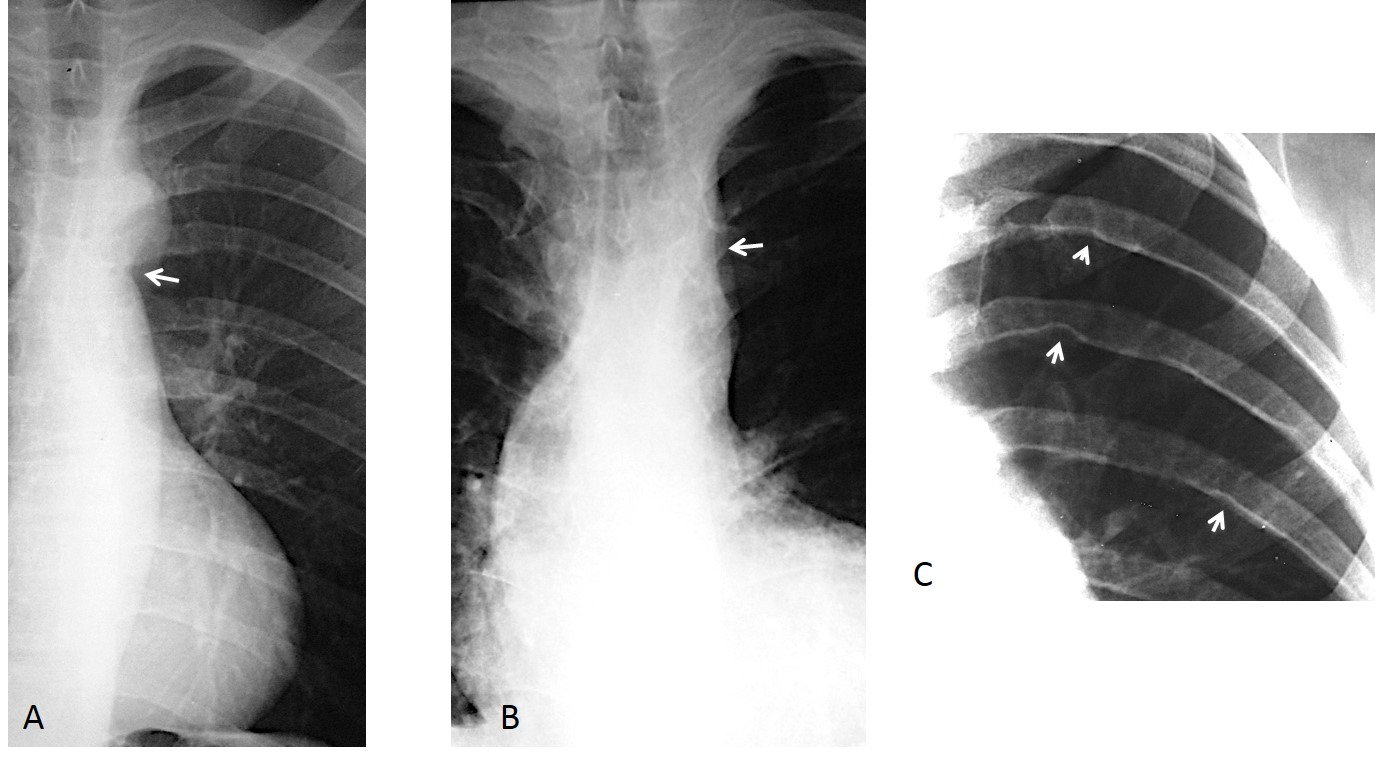

In aortic coarctation, the aortic knob shows a typical ‘figure three’ sign in about 60% of patients. The remainder show blurring of the upper aspect of the aortic knob, obliterated by the dilated left subclavian artery. Collateral circulation is responsible for the bilateral rib notching (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11 (above): figure three sign in aortic coarctation (A, arrow). In B, the top of the aortic knob is indistinct because of the enlarged subclavian artery (B, arrow). Typical rib notching (C, arrows).

Aortic pseudocoarctation is an uncommon malformation in which there is kinking of the aorta distal to the subclavian artery, without narrowing. There is no significant obstruction and no gradient across the kinking. The appearance on plain films is similar to that of true coarctation (Fig. 12). Patients do not have hypertension.

Fig 12 (above): pseudocoarctation with prominent ascending aorta and figure three knob (A, arrows). Angiogram shows kinking without narrowing (B, arrow).

A less common cause of bulging middle segment is an anterior mediastinal abnormality superimposed over the aortic segment. In these cases, CT must be performed to establish the diagnosis (Fig. 13).

Fig. 13 (above): 49-year-old man surgically treated for lung carcinoma. Postoperative film demonstrates a prominent mediastinal middle segment (A, arrow). Unenhanced CT shows encapsulated mediastinal fluid in that location (B, arrows).

Follow Dr.Pepe’s Advice:

1. A prominent middle segment at the right mediastinal border is usually secondary to ascending aorta dilatation.

2. Dilatation of the ascending aorta may be due to aortic valve stenosis, aneurysm, type A dissection, or aortic coarctation.

3. Non-aortic causes of a prominent second arch are anterior mediastinal abnormalities; these need CT confirmation.

….delle tre opzioni suggerite, penso che , sulla base della clinica, si può escludere la dissezione aortica, prossimale, tipo A, perche’ la clinica sarebbe stata drammaticamente molto più imponente…l’aneurisma dell’aorta ascendente è rarissima in un soggetto giovane( 31 anni),…. rimane una stenosi aortica sopravalvolare, il che spiegherebbe il dolore e l’ipertrofia del ventricolo sx…come opzione alternativa ci potrebbe essere una destroposizione aortica(ma dovremmo avere altri sintomi clinici dovuti ad una eventuale azione compressiva sulla trachea -esofago)….la diagnosi finale è un “work-team” con il cardiologo x un Ecocardiogramma ed RM cardiaca….Saluti dall’Italia e da Bari x una serena estate!!!!!

….mi dispiace contraddirti dott.Pepe ma la risposta esatta , sulla base dei radiogrammi standard è la 2: stenosi valvolare aortica….infatti la stenosi valvolare aortica può essere congenita( valvola bicuspide) ma anche acquisita, su base reumatica….solo con Angiotc e/ o RM possiamo evidenziare il difetto valvolare congenito….sui radiogrammi standard dobbiamo “genericamente” parlare di stenosi valvolare aortica, senza specificare il sotto-tipo….Scusami…un abbraccio a te ed al “mitico”joseph !

I believe this is a right aortic arch case with maybe pressure on tranchea.

Diagnosis: Aortic valve stenosis.

Explanation: There is enlargement of the ascending aorta + The left ventricle is enlarged too with mildly enlargede heart. In the same time there is no enlargement in the descending aorta.

PS: May be there is some aortic valve calcification.

2

Parece existir dos anomalías en el el contorno de la silueta cardíaca y vascular, uno de ellos en el lado superior derecho que sugiere dilatación de aorta ascendente (sin poder diagnosticar aneurisma ni disección mediante Rx) y otro correspondiente a crecimiento de VI en el lado inferior izquierdo. Sumando ambos me inclino hacia estenosis válvular aortica.

Por otro lado tronco pulmonar y arteria pulmonar principal izquierda no los consigo identificar con claridad. La radiografia PA podría estar un poco rotada aunque creo que es interpretable.

As minority of patients with aortic dissection have only vague chest pain (and I suspect widening of right paraspinal line) I wouldn’t exclude possibility of aortic dissection. So in addition to dilated ascending aorta and aortic stenosis I choose option 4: all of above.

Aortic valve stenosis producing sitting duck sign

You are correct, but I never heard about this sign.

My First choice is aortic valve stenosis us Fares says but we can’t easy exclude the other options so 4 All of the above.

Translocation of the right paravertebral line, mild dilatation of the left ventricle and dilatation of the ascending aorta. I think aortic valve stenosis with dissection and mediastinal hemorrhage ( D. all the above).

At this time of the day I believe I cal tell the right diagnosis. Patient had a bicuspid aortic valve with stenosis (correct answer). But the other two conditions also give dilatation of the ascending aorta in the plain film (second correct answer: all of the above).

More information tomorrow. Wish you a happy vacation!

Stenosi aortica.

aortic valve disease

I saw the case late, after the revelation of the answer.

Regarding the “sitting duck” sign, I found in the net that it is a sign for persistent truncus arteriosus in infants. Unfortunatelly I can’t copy-paste the image, but if you are interested here is the address where I found it;

http://www.medicalgeek.com/pediatrics/23912-article-cyanotic-congenital-heart-disease.html