Dr. Pepe’s Diploma Casebook: Case 61 – SOLVED!

Dear Friends,

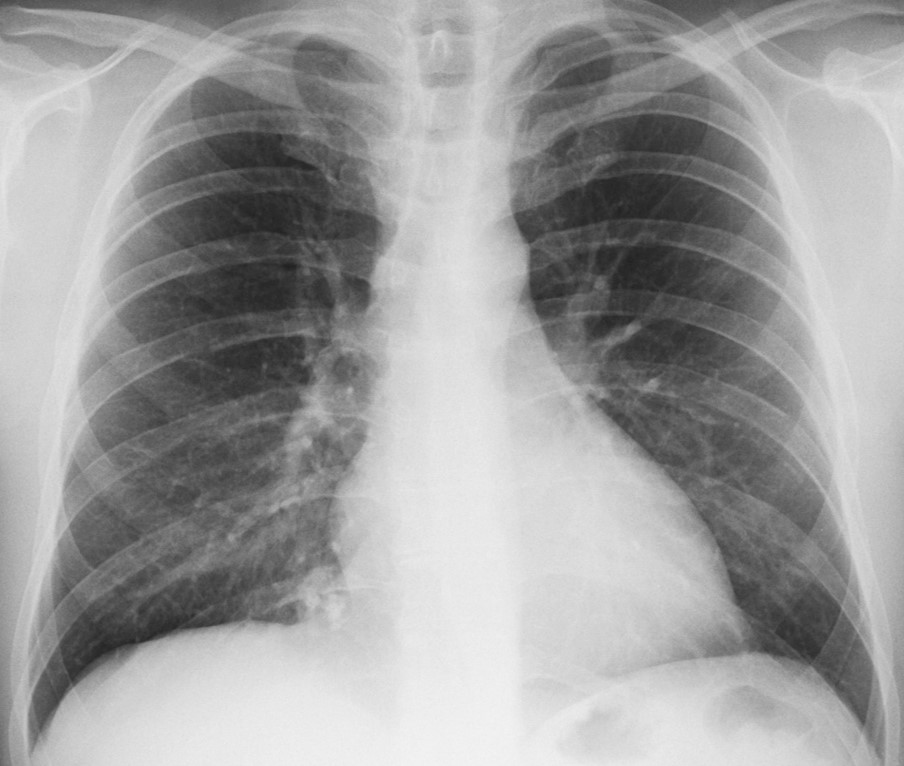

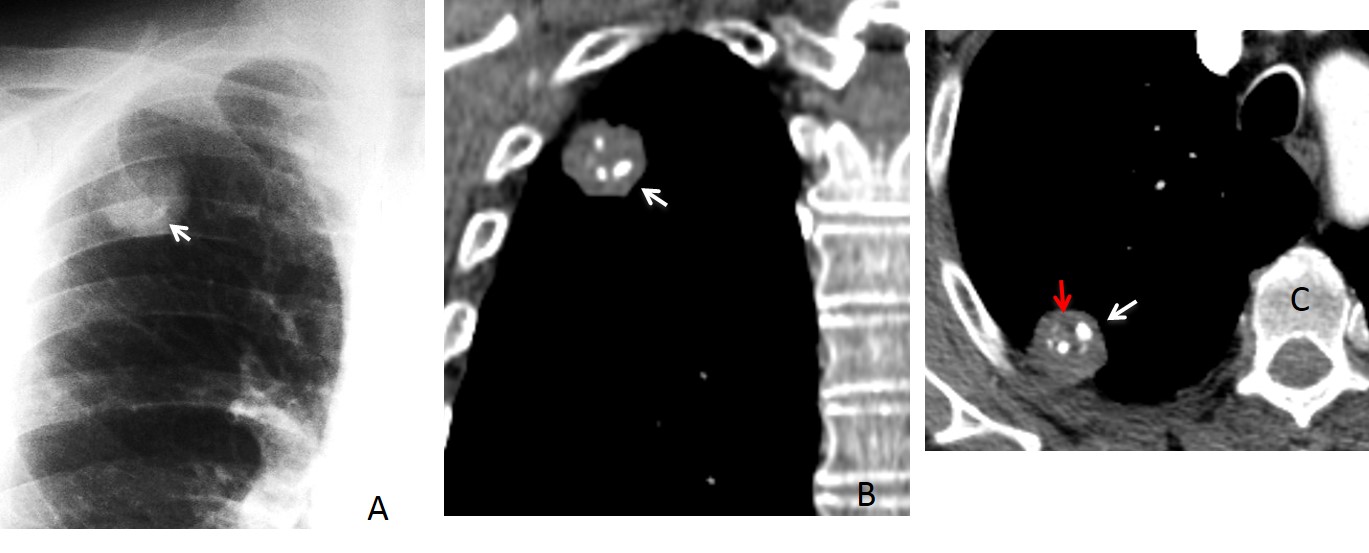

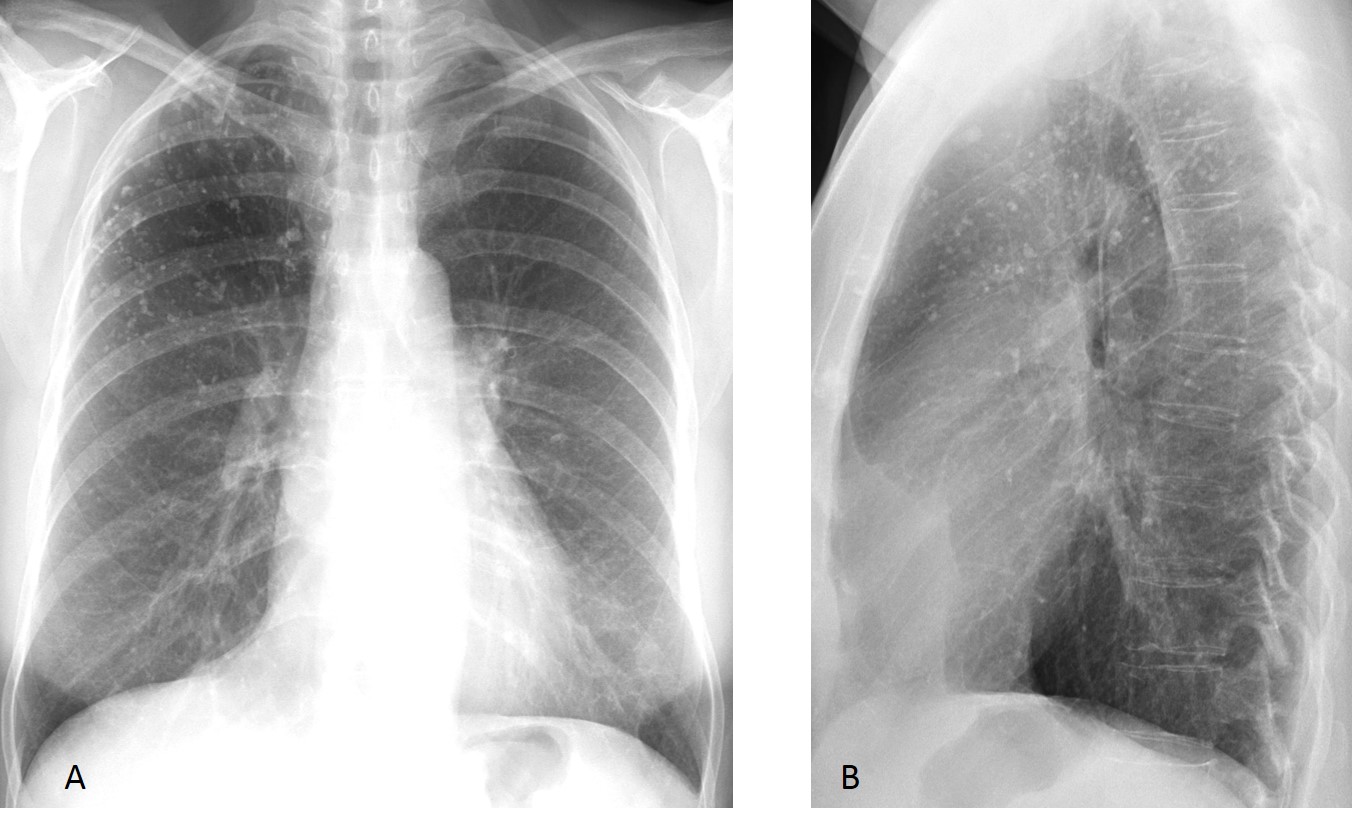

Today I am presenting pre-op chest films of a 48-year-old man with renal carcinoma. How will you define the lesion at the right cardiophrenic angle?

1. Benign nodule

2. Primary malignancy

3. Metastatic nodule

4. Can’t tell

Check the images below, leave your answer in the comments and come back on Friday for the answer.

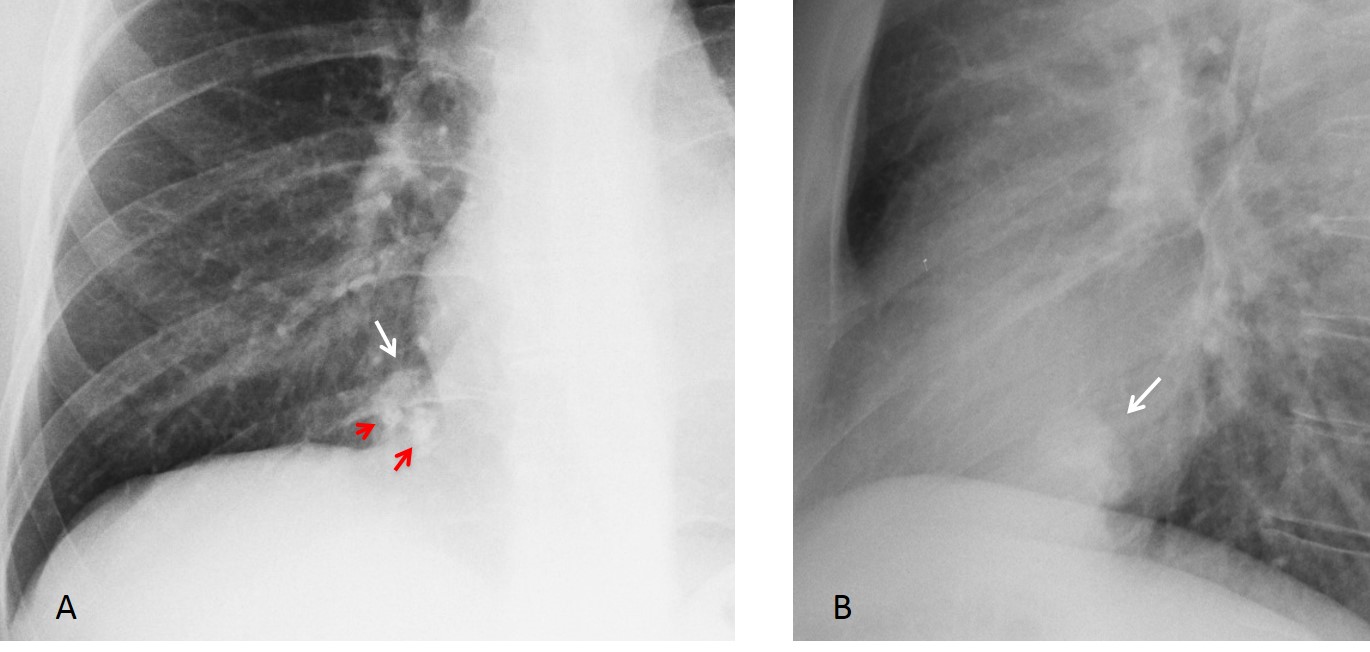

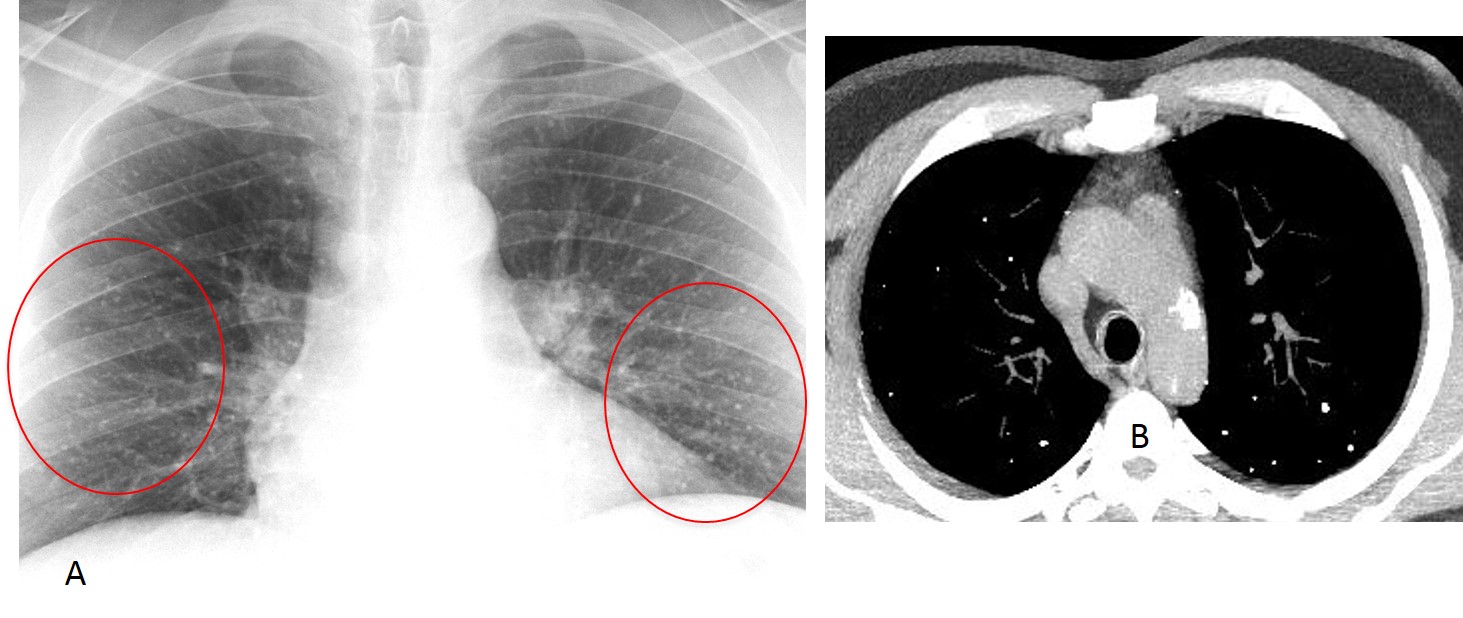

Findings: there is a pulmonary nodule at the right cardiophrenic angle (A,B, arrows) showing internal popcorn calcifications (A, red arrows). For practical purposes, a nodule with coarse calcifications on the plain film excludes malignancy and makes metastasis very unlikely. The best diagnostic option is: 1. Benign nodule.

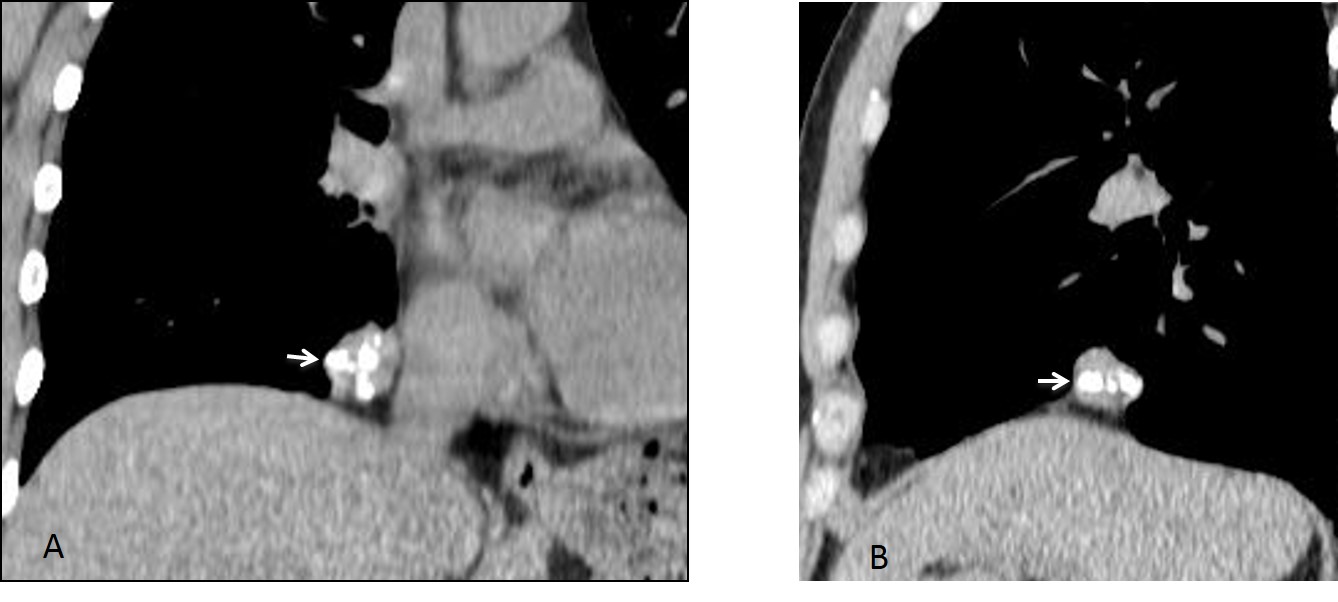

Coronal and sagittal CT confirm the intrapulmonary location of the nodule and the internal calcifications (Fig. 2, arrows).

Final diagnosis: pulmonary hamartoma.

This case is presented to discuss pulmonary calcifications visible on chest radiography. It is important to recognise them because they usually indicate a harmless process. Sometimes they can be difficult to identify because the high kVp technique used nowadays tends to ‘burn’ calcium. Pulmonary calcifications can be classified as: calcified nodules, regional calcifications (occupying part of one or both lungs) and widespread (miliary) calcifications.

A calcified pulmonary nodule on the plain film is a reliable sign of benignancy. The great majority occur in either hamartoma or granuloma. Other possibilities are much less frequent.

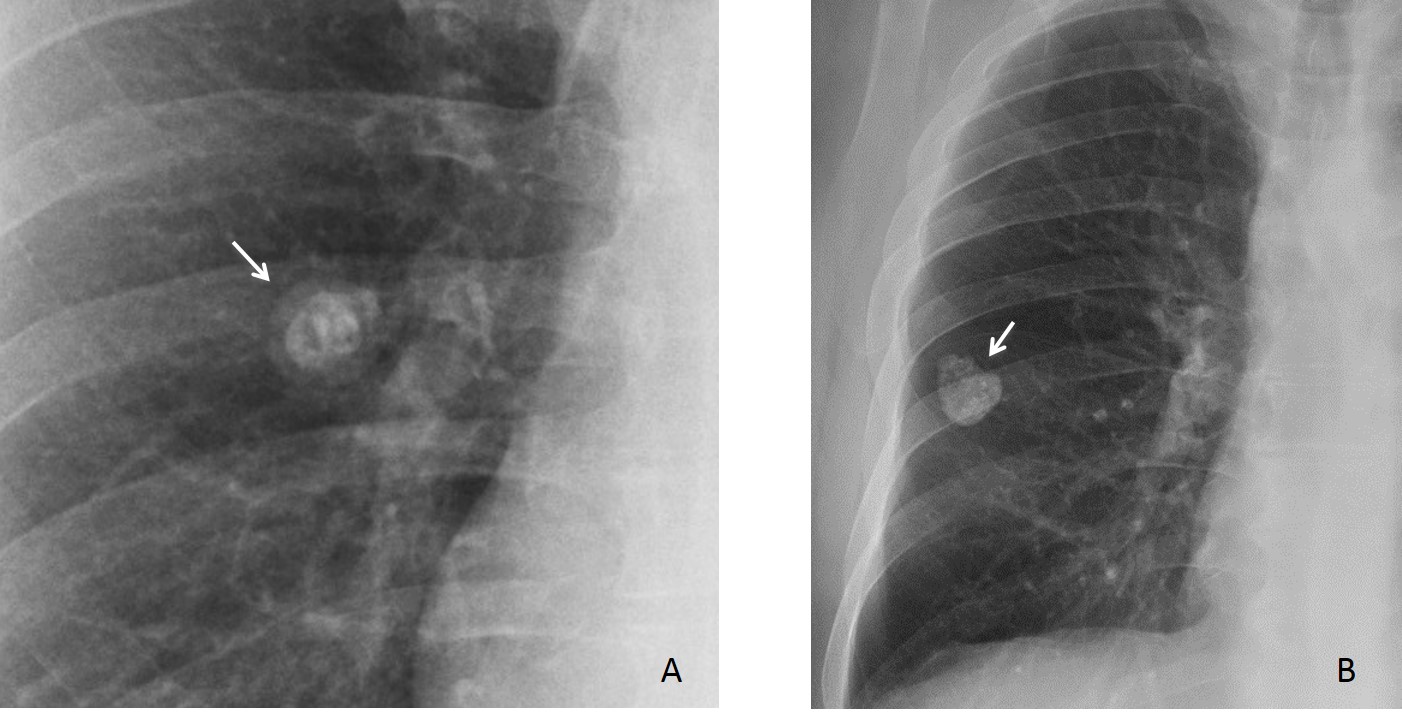

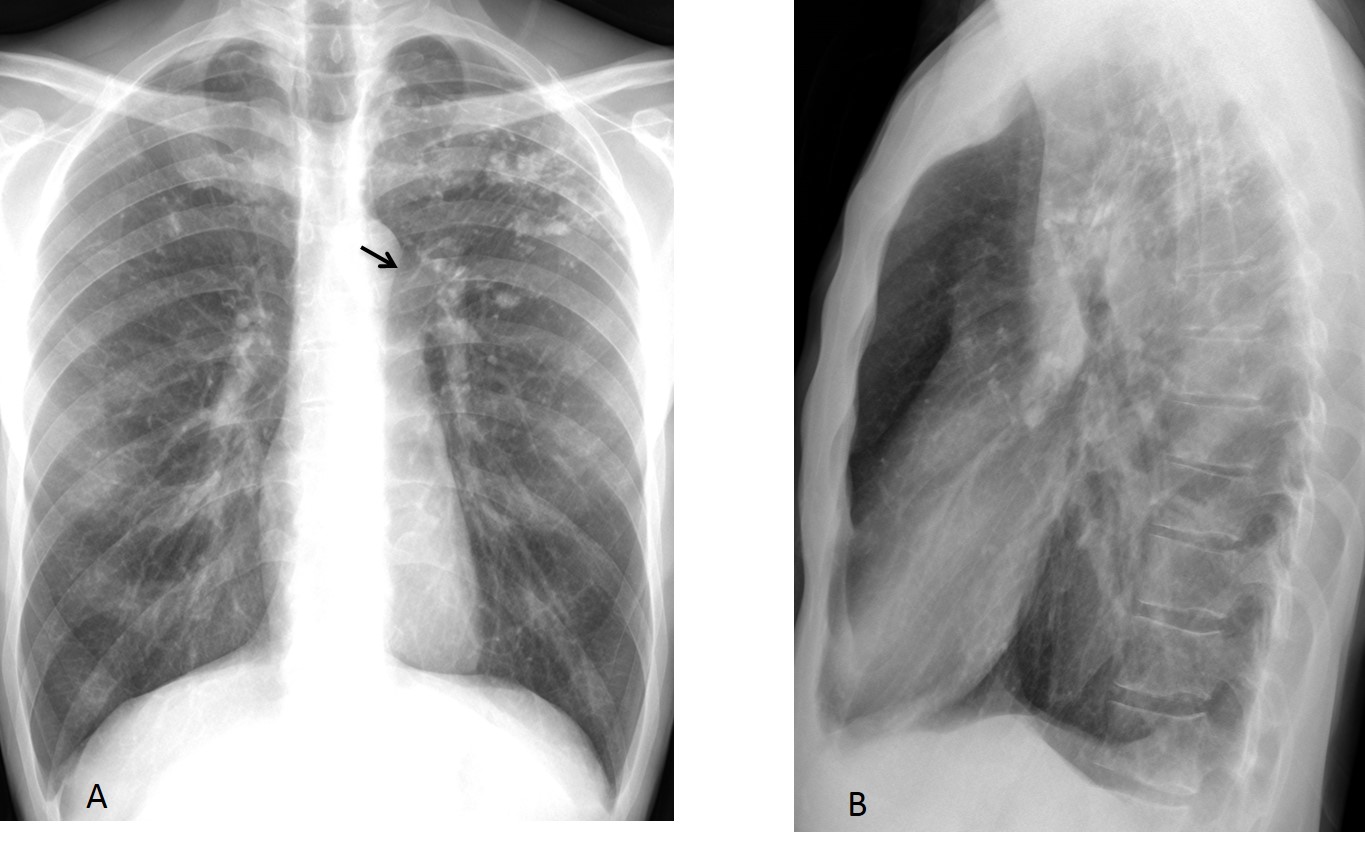

Hamartomas are the most common benign tumour of the lung. About 20% have calcifications on CT and less than 5% have visible calcium on plain radiography (Fig. 3). The popcorn type of calcification is highly suggestive of hamartoma, although it is also seen in some granulomas.

Fig. 3: RUL hamartoma. Nodule with coarse calcium on PA chest film (A, arrow). Coronal and axial CT confirm the popcorn calcifications (B,C, arrows) and depict fat within the nodule (C, red arrow).

Calcified healed granulomas are more frequent than hamartomas. The granuloma may show coarse calcification, central calcium, or heavy calcification (Fig. 4). The most frequent etiology is tuberculosis, except in areas where histoplasmosis is prevalent.

Fig. 4: TB granulomas in two different patients. In the first one, central bulls-eye calcium is visible (A, arrow). In the second patient, a heavily calcified nodule is seen (B, arrow).

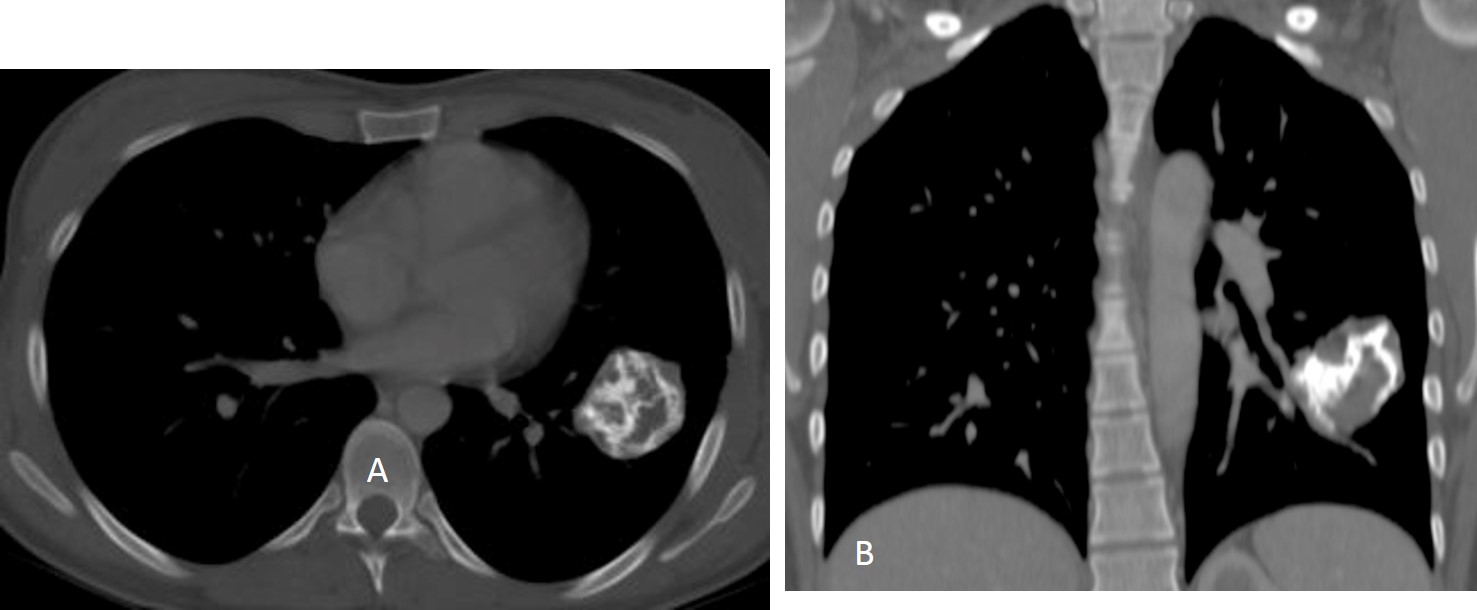

Uncommon causes of calcified nodules are primary or metastatic bone-forming tumours, treated metastases, amyloid nodules, and chondroid tumors (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5: Male patient with Carney’s triad and chondroma of the lung. Axial and coronal CT show the markedly calcified tumour (A,B arrows).

As mentioned earlier, a high kVp technique tends to ‘burn’ calcium, and even heavily calcified nodules may not be recognised on the plain film. For this reason, CT should be performed when calcium is suspected, but conventional radiography fails to show it (Fig. 6).

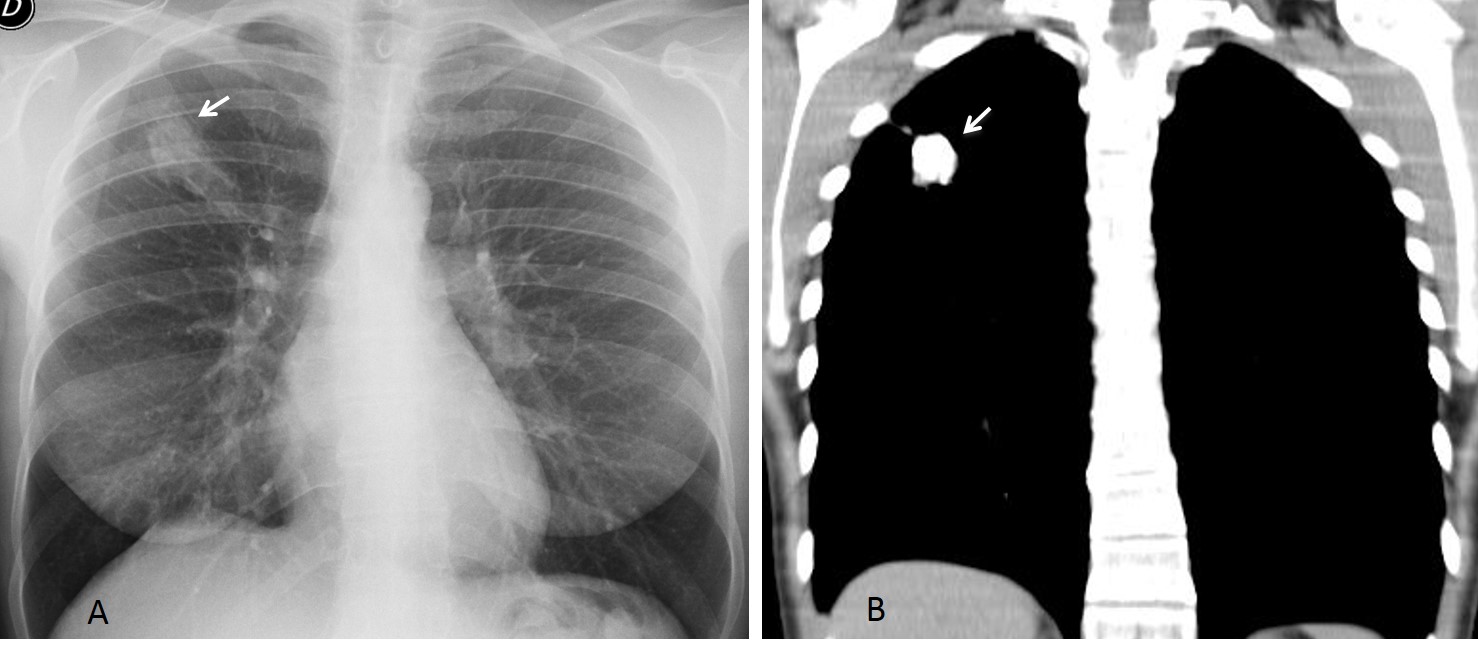

Fig. 6: 48-year-old woman with an apparently non-calcified RUL nodule (A, arrow). Coronal CT shows that the nodule is heavily calcified (B, arrow).

Regional calcifications are usually secondary to healed infectious granulomatous disease. Tuberculosis is by far the most common offender. In endemic areas, histoplasmosis infection may give the same appearance. Calcifications may be fine or coarse and occupy part of one or both lungs (Figs. 7 & 8).

Fig. 7: 59-year-old asymptomatic woman with history of previous TB. PA and lateral radiographs show numerous calcified nodules in the RUL.

Fig. 8: 46-year-old man with healed pulmonary TB. Numerous coarse calcifications are seen in the posterior apical segment of the LUL and a few in the right subclavicular region. Note elevation of the left hilum (A, arrow), secondary to fibrotic changes.

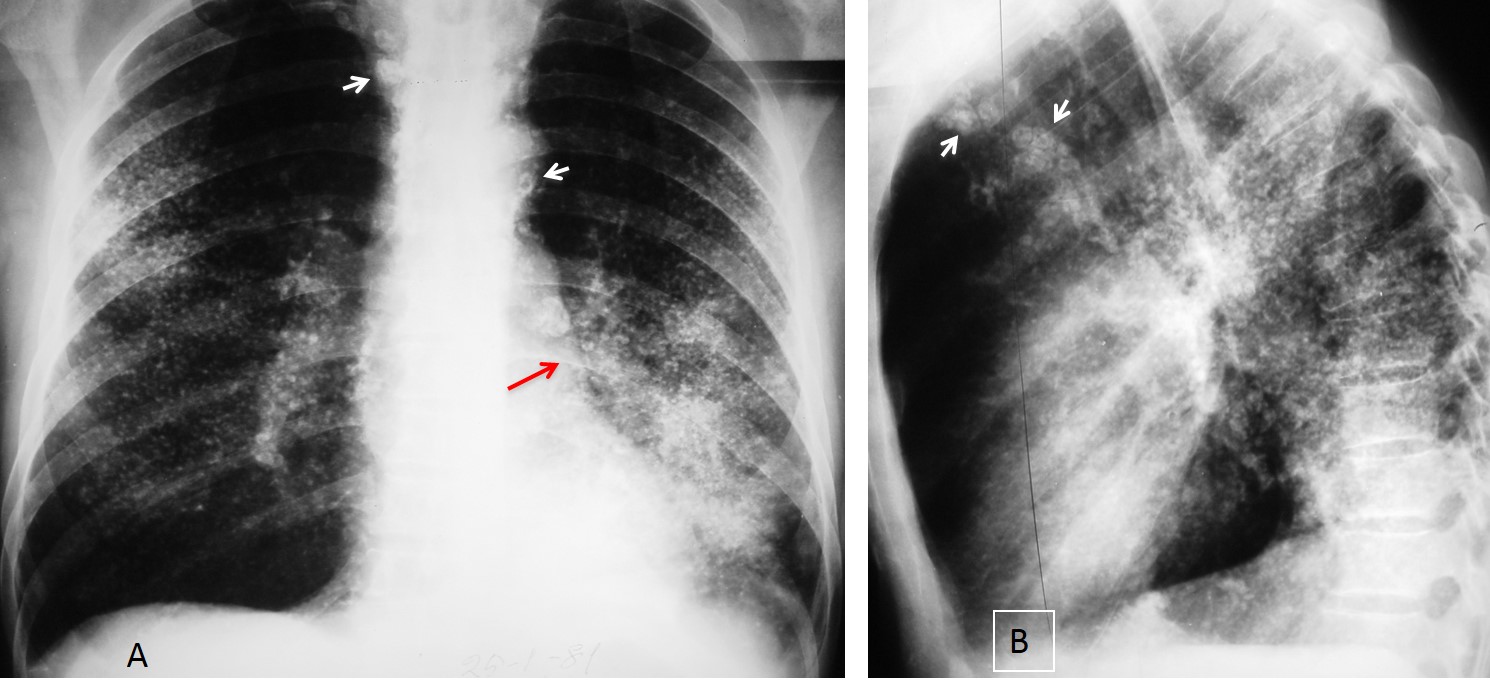

Widespread (miliary) calcifications occur in occupational diseases or after healed granulomatous infections. In endemic areas they may also be due to fungal infections. Silicosis is a common cause of miliary calcium. About 10-15% of silicotic nodules calcify. An association with egg-shell calcifications in the mediastinal lymph nodes is almost pathognomonic of silicosis (Fig. 9).

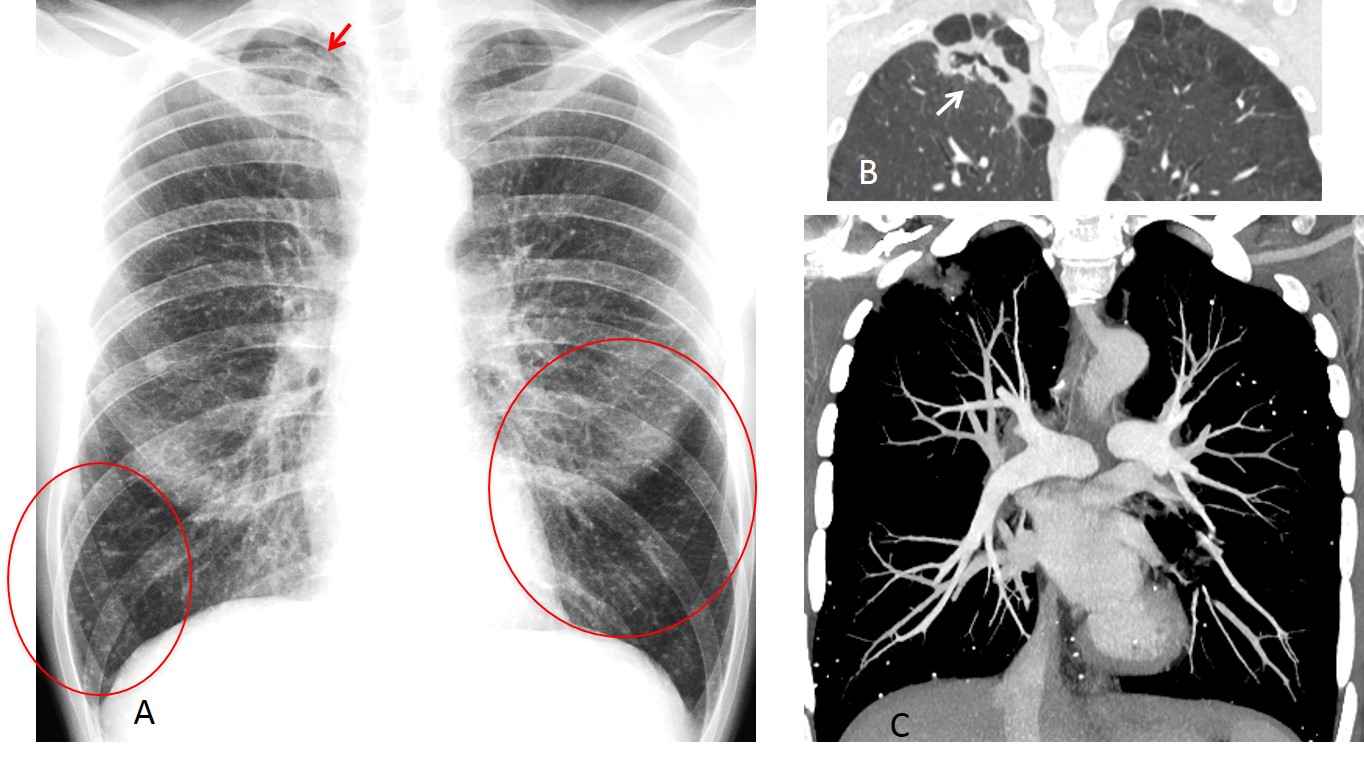

Fig. 9: calcified miliary nodules in a 57-year-old miner with silicosis. Note egg-shell calcifications in the mediastinal nodes (A,B, white arrows). The increased LLL opacity and downward displacement of the left hilum (A, red arrow) is secondary to an incidental bronchogenic carcinoma.

Miliary calcifications secondary to healed varicella pneumonia are not uncommon in my experience (Fig. 10). Unlike what occurs in silicosis and TB, the mediastinal lymph nodes do not calcify. Due to the small size of the nodules, calcium may go unrecognised by the untrained eye. When in doubt, CT will clarify the findings (Fig. 11).

Fig. 10: 52-year-old woman with a history of varicella pneumonia at the age of 11 years. Supine chest film shows miliary lung calcifications (A, arrows), confirmed with coronal CT (B).

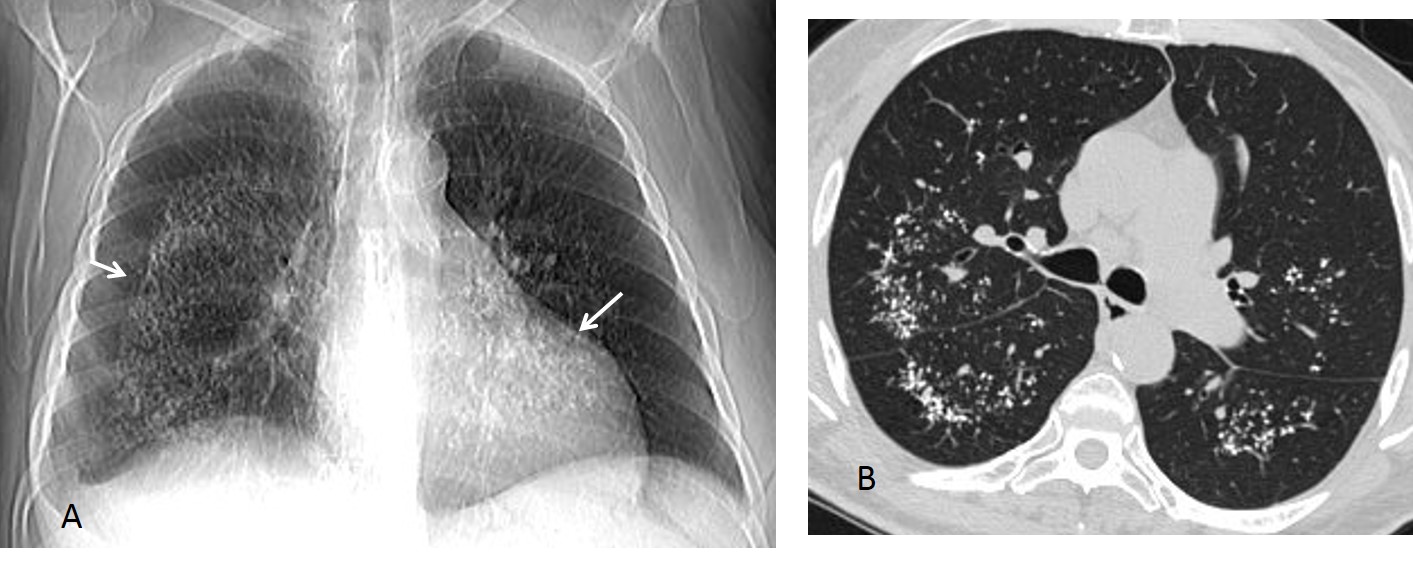

Fig. 11: Male patient with inconclusive findings of miliary calcium on the plain film (A, circled areas). Axial CT (B) confirms the presence of calcium. He had a history of varicella pneumonia.

Cavitary TB with bronchogenic spread is another cause of pulmonary calcifications. The healed granulomas coexist with chronic TB changes (Fig. 12). It is important to know that miliary TB does not calcify.

Fig. 12: 42-year-old HIV+ man with a history of TB. PA chest shows numerous miliary calcifications (A, circled areas). There is an ill-defined apical opacity (A, red arrow) which represents a partially collapsed cavity (B, arrow). Coronal CT confirms the miliary calcium (C).

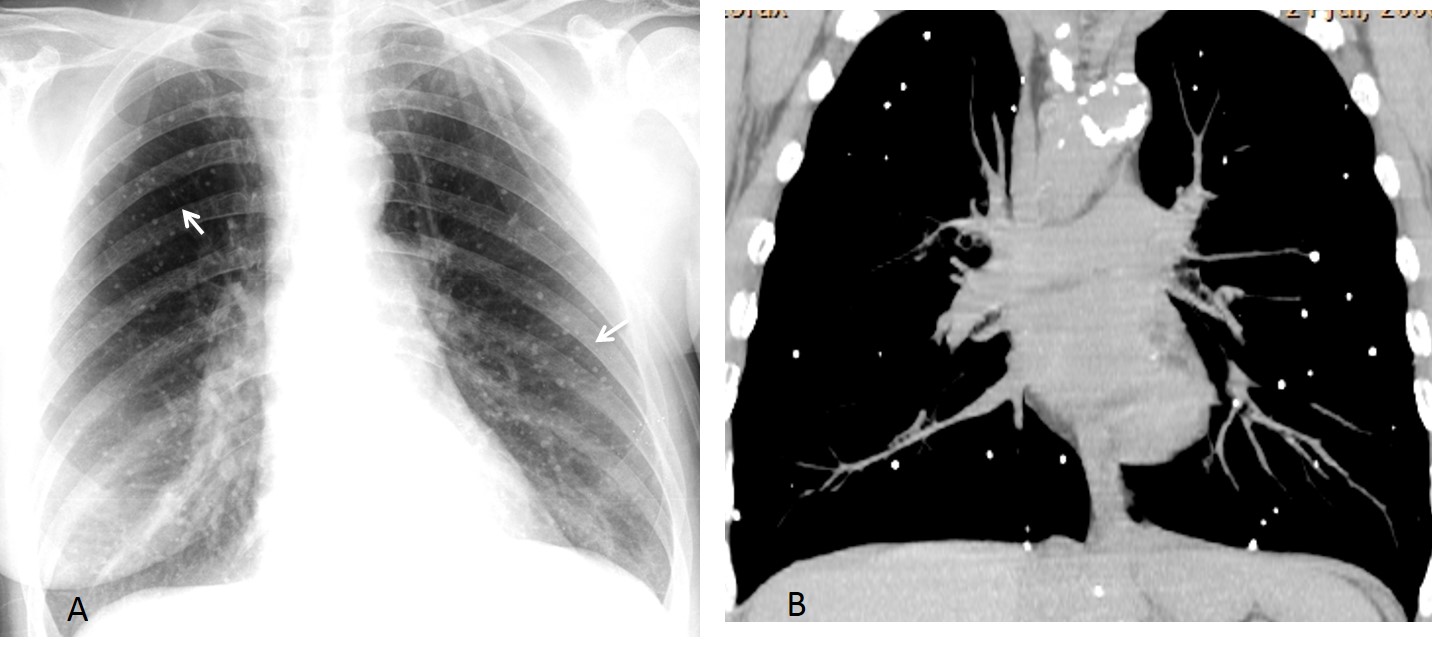

Diffuse pulmonary calcification occurs mainly in hypercalcemic states (eg. chronic renal failure, amyloidosis, primary hyperparathyroidism). Calcium is seldom recognised on plain radiography. The paradigm of all these conditions is alveolar microlithiasis, a disease of unknown etiology in which tiny calcifications fill the alveoli (Fig. 13).

Fig. 13: 48-year-old male with pulmonary alveolar microlithiasis. Scout film shows diffuse calcium in the medulla of both lungs (A, arrows). Axial CT confirms the central location of the calcifications (B).

Follow Dr.Pepe’s Advice:

1. Pulmonary calcifications visible on plain films are usually secondary to a harmless process.

2. Calcium may be difficult to recognize on radiography due to a high kVp technique.

3. A calcified nodule on radiography is benign until proven otherwise.

4. The most common causes of miliary calcium are silicosis and healed varicella pneumonia.

It looks like hamartoma (popcorn calcifications?). 1. Benign nodule

….3 anni prima il Cr renale….a quell’epoca sicuramente ha fatto un rx-torace pre-operatorio….se la “coin lesion” non era presente potremmo prendere in considerazione una metastasi o un tumore primitivo”metacrono”…se era già presente allora in base alle caratteristiche dei margini, “regolari” e delle calcificazioni intranodali, “grossolane” , la prima ipotesi diagnostica è per AMARTOMA polmonare!

hamartoma !!!! dont touch lesion

Benign nodule, very well defined. This is a common site for pleuro-pericardiac cyst. But considering internal dense foci may go more with hamartoma.

1- benign nodule ( Hamartoma)

What can I say? Yuo are all very smart!

Harmatoma

Can’t tell

Hamartoma

Benign nodule.

hamartoma, lesion show calcification.

Benign nodule

Benign nodule,hamartoma most likely due ti popcorn calcification