Facial genetics and forensics take centre stage at ECR

Watch this session on ECR Live: Friday, March 3, 10:30–12:00, Room B

#ECR2017

Forensics and facial genetics will be in the spotlight at ECR 2017 as the ‘ESR meets Belgium’ session offer a look at medical imaging’s most original contributions to healthcare and crime investigation.

Advanced decomposition of brain MRI or facial 3D surface images into modules, tailored for associations with underlying genetic variations.

Dr. Peter Claes from Leuven, Belgium, will present his work in facial genetics in a session titled ‘Imaging genetics and beyond: facial reconstruction and identification’.

Claes is a senior research expert in the Medical Image Computing research group of the Processing of Speech and Images division of the Electrical Engineering department at Leuven Catholic University.

He uses CT, MRI and 3D surface imaging modalities to grasp the link between people’s appearance and underlying genetic variations.

“Your appearance is genetically driven. In families there’s a strong link, even more so between identical twins, who share the same DNA profile and almost the same face. Physical features also influence your brain, the way you think. A lot of facial characteristics are shared, for example in Down’s syndrome patients, who present with the same features whether they are European or Asian,” he explained.

The link between genetic disorders and facial genes has been of interest to scientists for a while, but research is slow and tedious.

Claes became interested in facial genetics after working in craniofacial morphometrics to help correct morphological abnormalities and anomalies, and in craniofacial reconstruction to identify victims.

To help decipher facial genetics, Claes uses the computer-based craniofacial reconstruction programme he developed for victim identification, and combines 3D surface processing, statistical modelling, analysis, mapping and prediction techniques. He has also created an array of algorithms and software for investigators who plan to use 3D facial datasets. Last year, he also co-organised the first international workshop on facial genetics in London.

The challenge in using images for the study of facial genetics is to focus on and measure the right elements, for instance the space between the nose and upper lip. Claes analyses the nearly 10,000 faces in his database in combination with imaging of brain genetics and blood vessel structures in the brain, such as the circle of Willis.

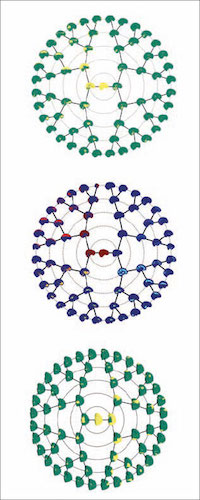

Instead of analysing voxels, which “would take forever”, he relies on powerful software to map voxel images spatially, as shown in the images illustrating this article.

“Facial genetics can be useful in both genetics and forensics, by predicting genes from the face and faces from the genes, and more globally the link between the face and DNA points to the whole area of personalised medicine,” Claes added.

“We try to find genes associated with brain morphology and faces. And for faces, we try to predict the face from genetics, which is useful for identification in relation to crime scenes, in forensics and DNA matches,” he said.

Victim identification will also be the focus of Dr. Wim Develter’s talk on high-end CT imaging in forensic pathology.

A forensic pathologist at the University Hospitals of Leuven, Dr. Develter will highlight the role of CT in Disaster Victim Identification (DVI), a field in which he has gained experience ever since he worked in the aftermath of the Tsunami in Thailand in 2004.

CT is important in DVI and its use depends on the on-going disaster, he said.

“During the MH17 Ukraine plane crash in 2014, CT was very useful for victim identification. After the terror attacks in Brussels airport in Zaventem in March 2016, CT helped us not only with the identification but also later with the enquiry,” he said.

Develter and his colleagues were responsible for the triage after the MH17 plane crash. They opened the coffins that came from Ukraine, inventoried the contents and selected which bodies would go to a specific identification chain (full ‘classic’ identification or body fragments for anthropology and DNA sampling), in order to optimise and accelerate the identification process. Before this triage, a CT examination was performed to facilitate the operation and identify important objects such as personal belongings, prostheses, shrapnel, or explosives.

“Despite the advantage of CT the coffins had to be opened and soon the biohazard risk appeared. During the amateurish recovery of the bodies in Ukraine, chemicals were used for body preservation (a toxic and lethal dose of formaldehyde was measured) and apparently some bodies had remnants of toxic rocket carburant. After the necessary safety measures, our job continued,” he said.

CT also helps to find relevant information for the ongoing medicolegal investigation; the modality is used to help identify traces from the blast such as objects from the explosives. The injury pattern helps to determine the cause and manner of death. When pathologists and radiologists can provide this information it can help police with the inquiry.

Protocols can change according to the situation and the forensic team must adapt to local circumstances. “In Thailand I could choose between ventilation or lighting. It was more than 36 degrees in the morgue; I had some air or light but no electricity for both,” Develter said.

In Europe, DVI teams can contract mobile CT scans anywhere and receive the material within 24 to 36 hours. These services are typically used for clinical purposes in hospitals that need CT examinations once or twice a week but have no budget to purchase a scanner.

Regarding DVI and terror attacks Develter is also responsible for the education of the forensic pathologists in his department and is involved with the national Crisis Centre of Internal Affairs.

In his lecture, he will insist on the necessity for pathologists within DVI teams to be properly trained, through standard exercise and simulation, to extract the maximum information from the crime or disaster scene and the subsequent investigation of the victims. “If your pathologist is not trained well, crucial information can be lost,” he said.

ESR meets Session

Friday, March 3, 10:30–12:00, Room B

ESR meets Belgium

EM 1 Emergency radiology

Presiding:

G. Villeirs; Ghent/BE

P.M. Parizel; Antwerp/BE

» Introduction

Villeirs; Ghent/BE

» Additional value of dual-energy CT in abdominal emergencies

Danse; Brussels/BE

» High-end CT imaging in forensic medicine: experience after recent Brussels terror attacks

Develter; Leuven/BE

» Interlude: Imaging Belgian food

Verstraete; Ghent/BE

» Imaging genetics and beyond: facial reconstruction and identification

Claes; Leuven/BE

» Interlude: The Belgian Museum of Radiology

Van Tiggelen; Brussels/BE

» Panel discussion: Acute pathology: emergency radiologists or organ subspecialists?

(Images provided by Dr. Peter Claes.)