Dr. Pepe’s Diploma Casebook: Case 97 – A painless approach to interpretation (Chapter 4) – SOLVED!

Dear Friends,

Now that we’ve looked at the three key questions to ask when facing a chest radiograph (chapters 1, 2 and 3), we move on to the interpretation of pulmonary lesions.

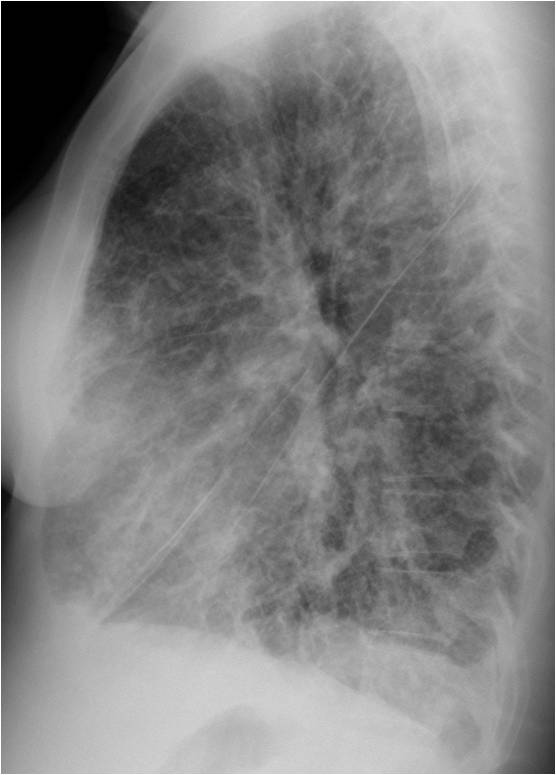

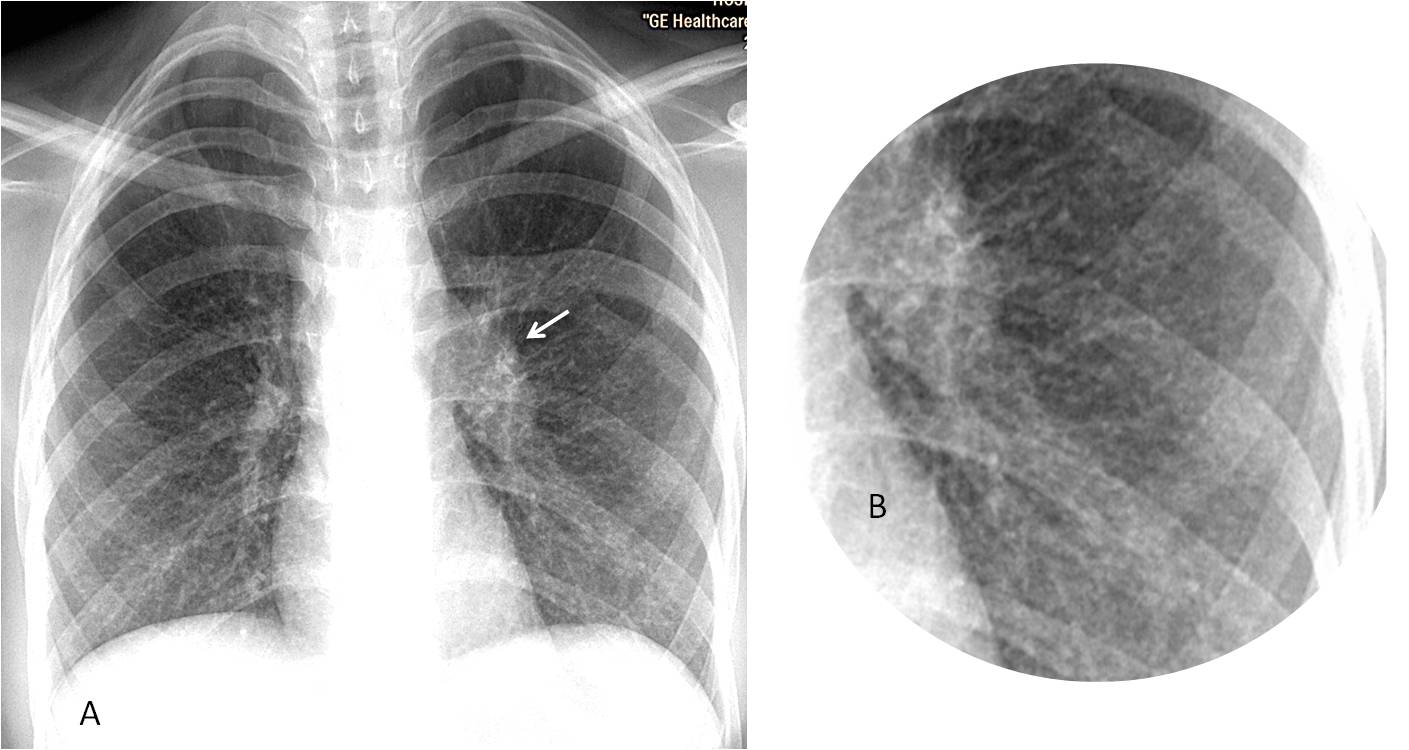

Today I am showing chest radiographs of a 31-year-old woman with marked dyspnoea for the last three days.

What would you call the predominant pattern?

1. Reticulonodular

2. Septal

3. Air-space disease

4. None of the above

Check the images below, leave your thoughts in the comments and come back on Friday for the answer.

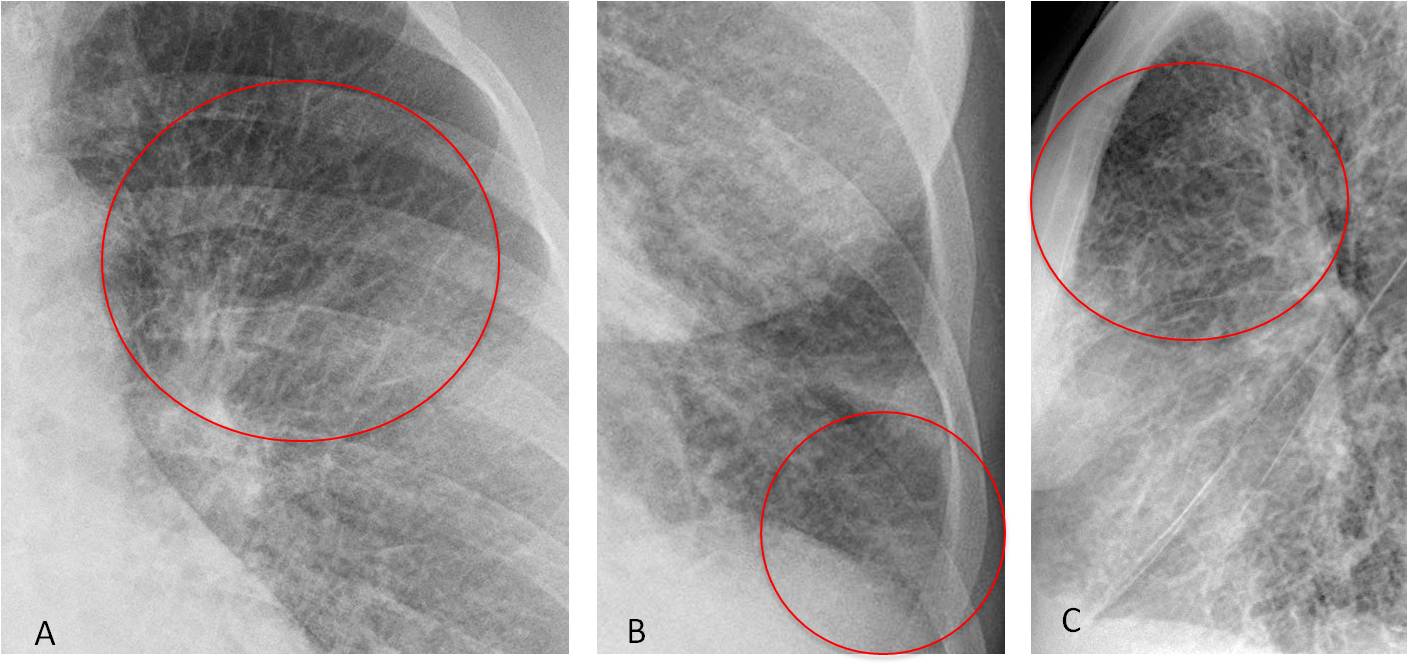

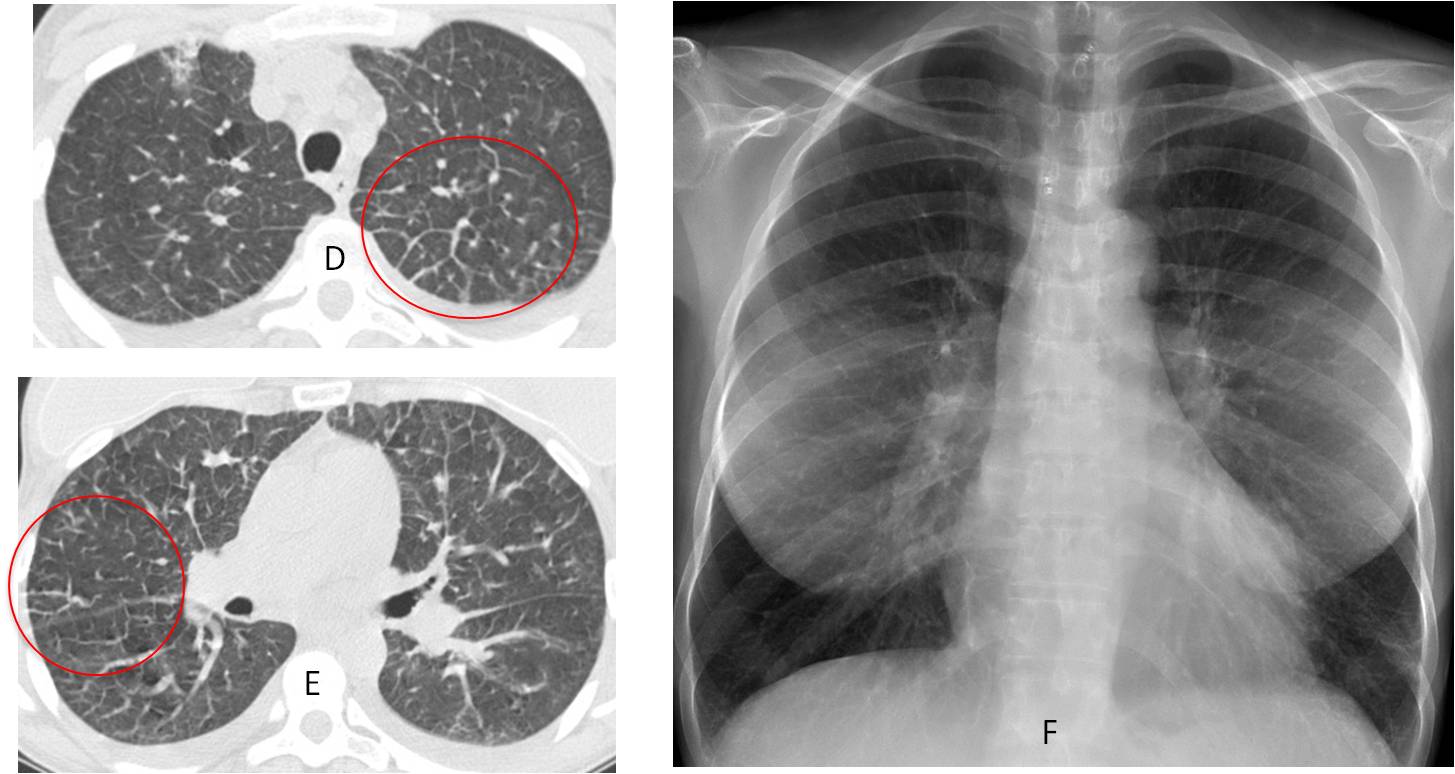

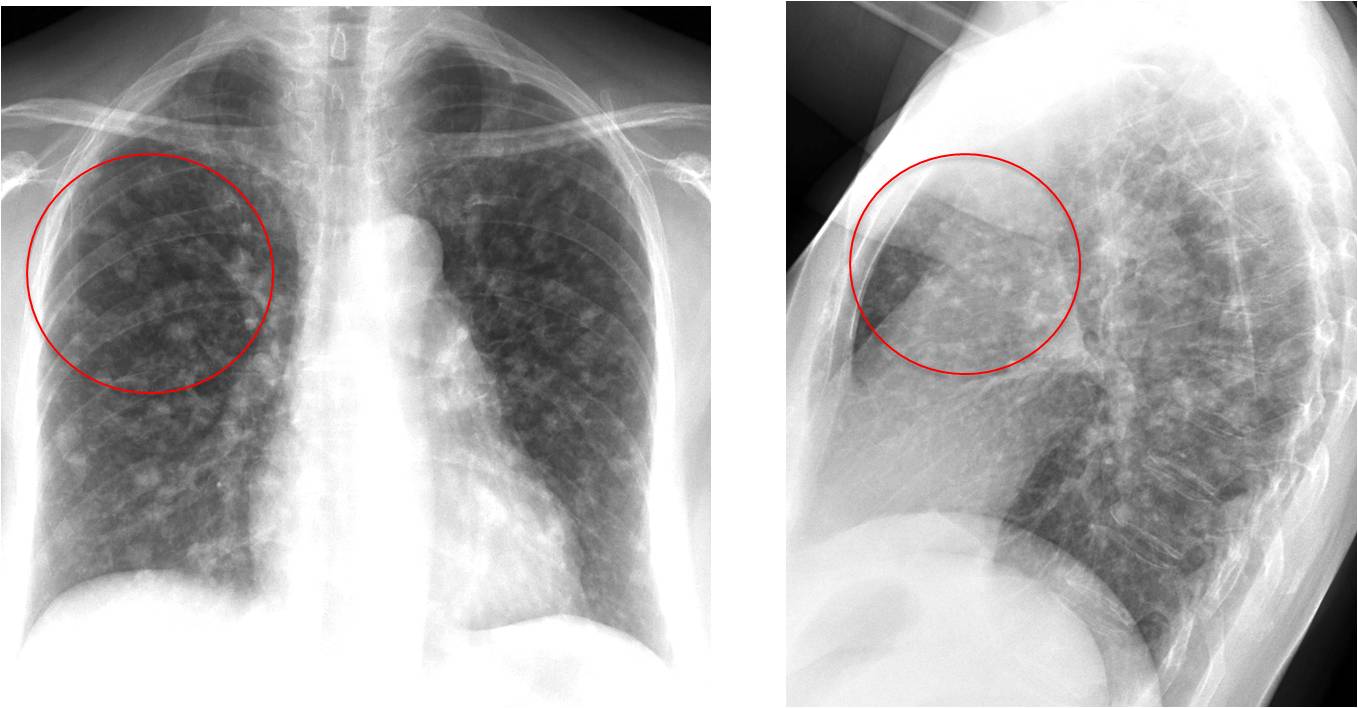

Findings: PA radiograph shows numerous Kerley A and B lines (A and B, circles). The lateral view shows Kerley A lines in the anterior clear space (C, circle). The appearance is typical of a septal pattern (see Diploma Casebook case 53).

CT confirms the presence of numerous Kerley lines (D and E, circles). After treatment, PA film taken two weeks later (F) shows disappearance of the septal pattern.

Final diagnosis: Pulmonary oedema secondary to an autoimmune reaction in a lupus patient.

Unlike mediastinal and extrapulmonary lesions, which are relatively easy to identify, pulmonary lesions have several appearances that are defined by their patterns. In this presentation I would like to describe the most common pulmonary patterns. To narrow down the differential diagnosis, they should be complemented with other features:

1. Evolution (acute vs. chronic)

2. Extension (localised vs. widespread)

3. Location within the lung

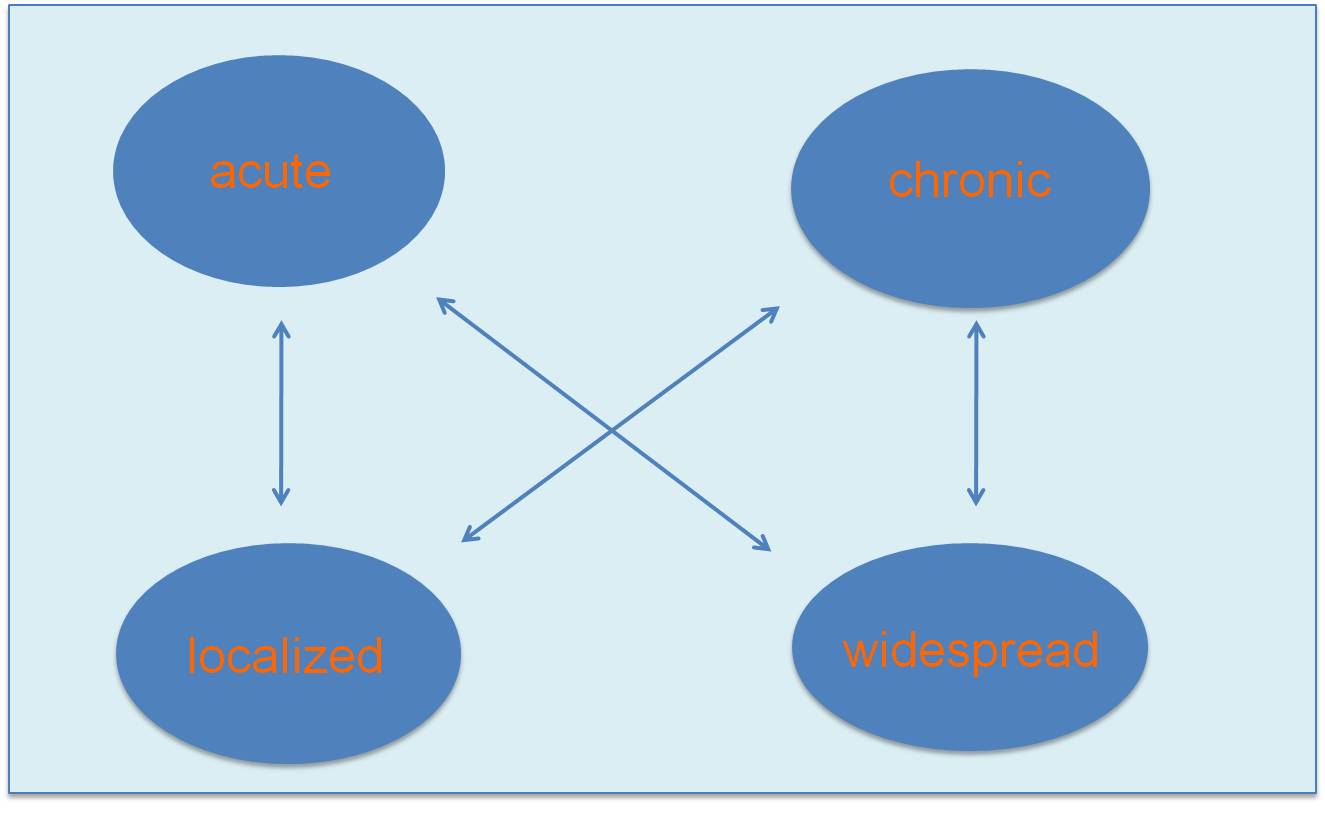

The relationships between evolution and extension are easily seen in the diagram below (Fig. 1).

As this presentation develops, I will also show examples of how the location may help the diagnosis.

Fig. 1

Fig. 1. Diagram showing the relationships between the extension and evolution of pulmonary conditions. They can have four presentation forms: acute localised, acute widespread, chronic localised, and chronic widespread.

A description of all the pulmonary patterns is beyond the scope of this presentation. In my opinion, the most common (and easy to interpret) are:

Localised

Air-space pattern

Lobar collapse

Solitary pulmonary nodule

Widespread

Air-space pattern

Multiple nodules

Miliary pattern

Septal (lymphatic) pattern

I believe reticular, reticulonodular, and honeycomb patterns are difficult to identify in plain films and should be investigated directly with CT.

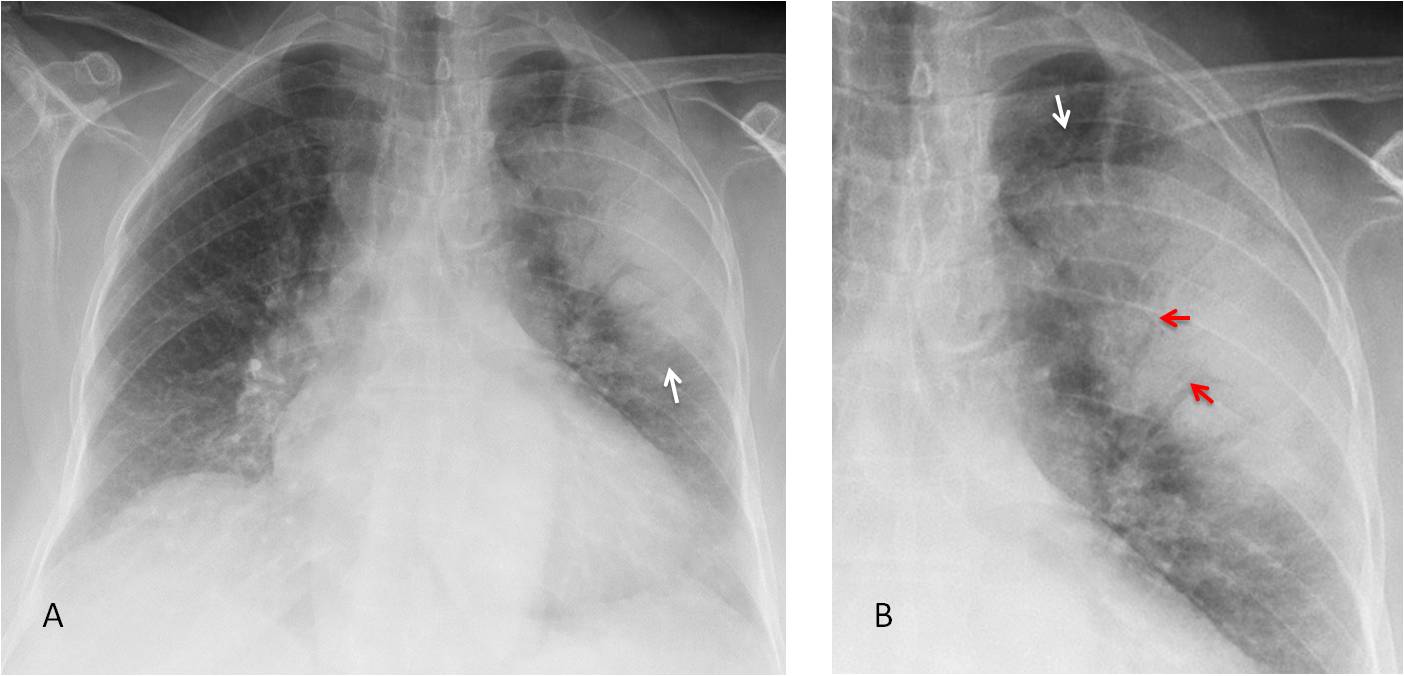

The air-space pattern appears as a pulmonary opacity with hazy margins (Fig. 2). When visible, an air bronchogram is a pathognomonic feature. The most common cause of air-space pattern in an acutely ill patient is pneumonia, followed by pulmonary infarct and haemorrhage after a contusion.

Fig. 2

Fig. 2: 69-year-old woman with fever. PA chest film shows a typical air-space pattern, with an ill-defined contour (A and B arrows) and air-bronchogram, better seen in the cone down view (B, red arrows). Diagnosis: Acute pneumonia.

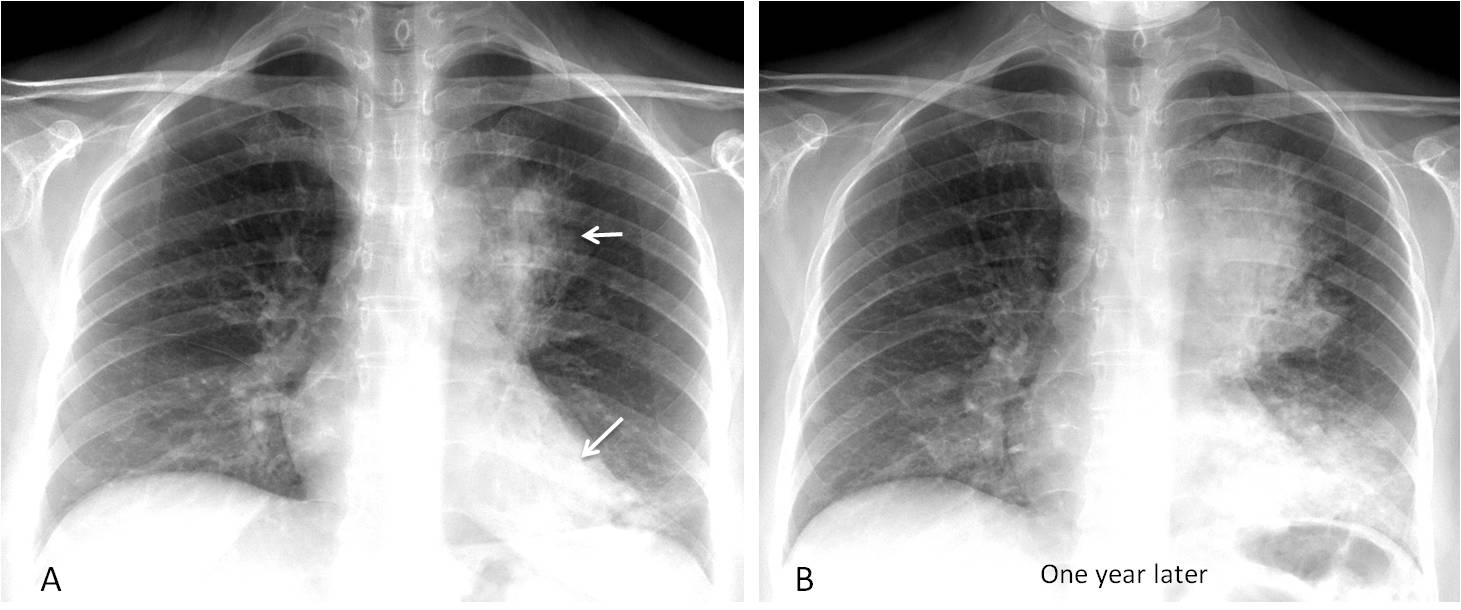

Chronic localised air-space pattern can have several causes. The most common are torpid infection, organizing pneumonia, and adenocarcinoma (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3

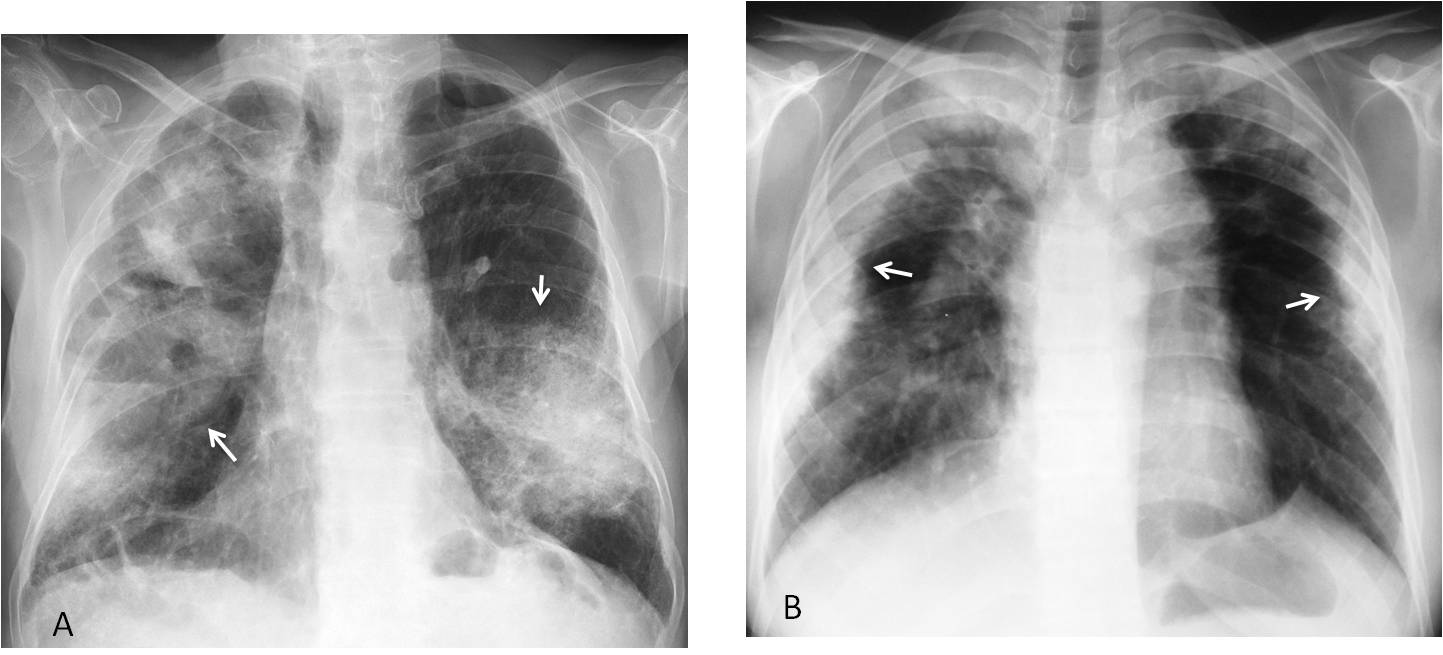

Fig. 3. 46 y.o. woman with chronic cough. Initial radiograph shows an air space pattern in the left upper and lower lobes (A, arrows). One year later (B), the infiltrates have grown. Diagnosis: adenocarcinoma.

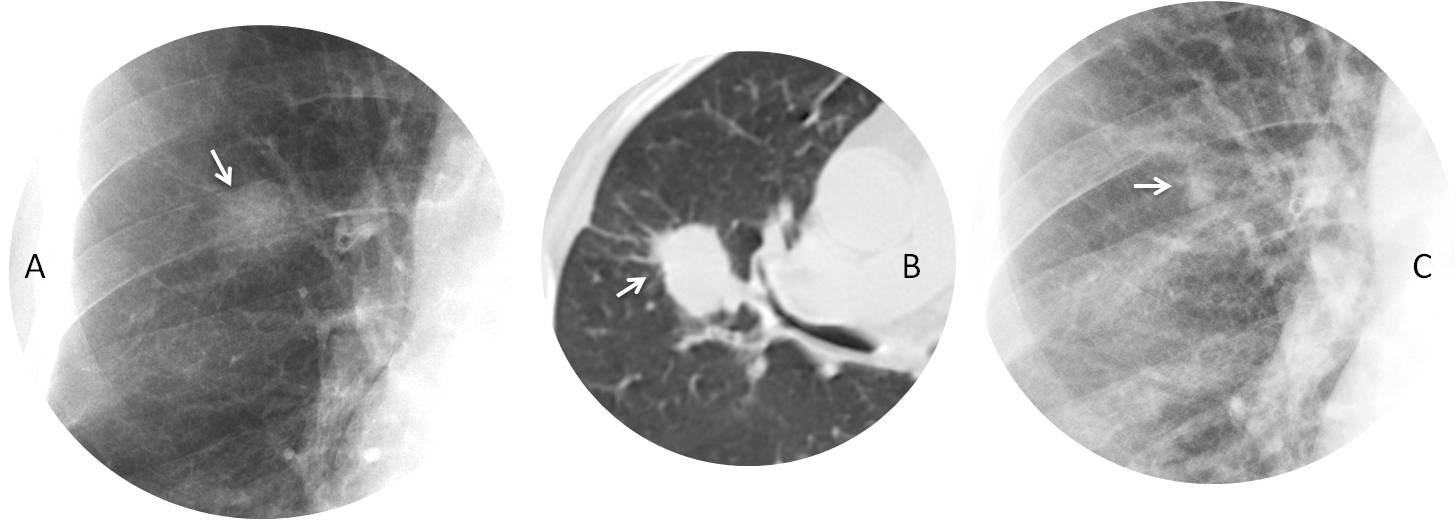

Solitary pulmonary nodule (SPN) is defined as a well- or poorly-defined rounded opacity up to 3cm in diameter. In plain films, the best criterion to determine whether the SPN is benign or malignant is evidence of growth (or lack of growth). For that reason, it is essential to compare with previous films, when available. A nodule that has grown in the interval is probably malignant and should be acted upon (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4

Fig. 4. Indeterminate nodule in the right lung (A, arrow). CT shows irregular margins, a sign suggestive of malignancy (B, arrow). Plain film one year earlier shows the nodule, considerably smaller and missed at that time (C, arrow). Diagnosis: Adenocarcinoma.

It is important to recognize lobar collapse because most cases occurring in adults are secondary to malignancy. It is identified by increased opacity and loss of volume of the affected lobe, with retraction of neighbouring structures (fissure, hilum, trachea) due to the volume loss (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5

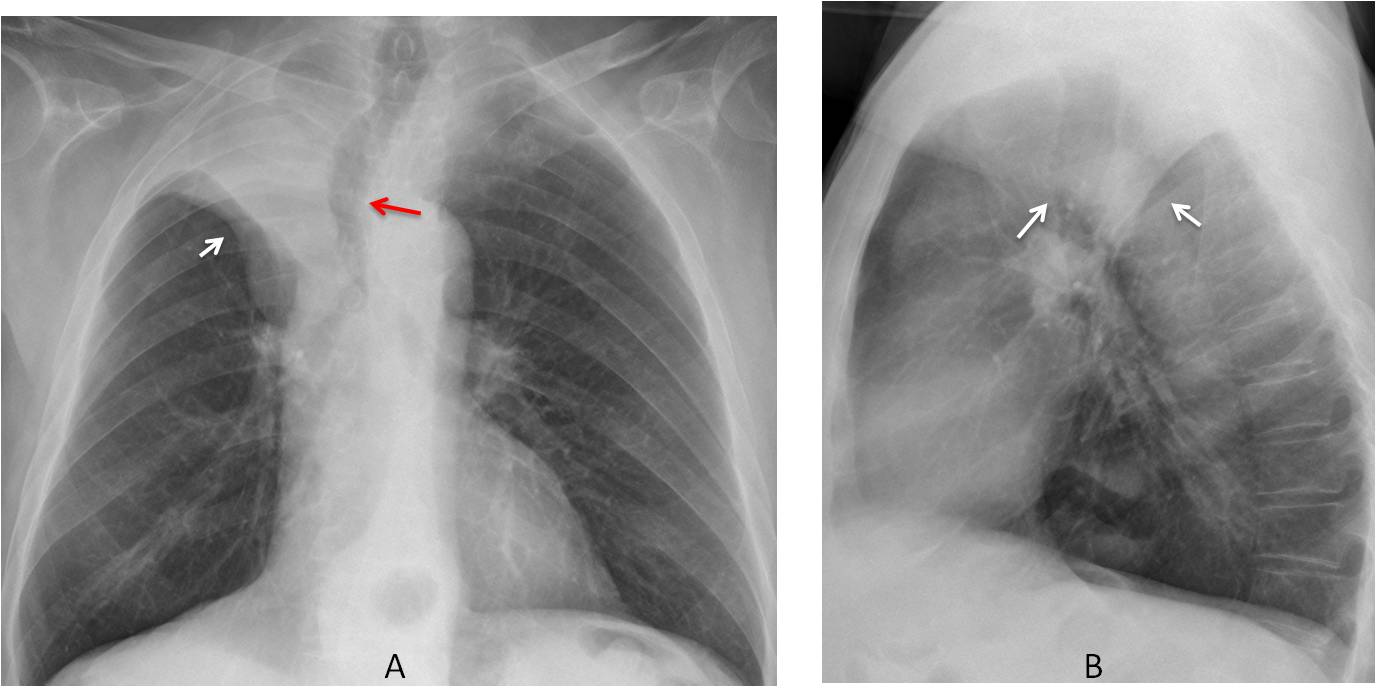

Fig. 5. 61-year-old man with cough and haemoptysis. PA radiograph shows typical RUL collapse with elevation of the minor fissure (A, white arrow) and tracheal retraction (A, red arrow). The lateral view shows the typical umbrella-shaped lobe (B, arrows).

Diagnosis: Carcinoma of RUL bronchus.

Among the widespread conditions, air-space pattern is probably the most common. Usually it adopts a butterfly-wing appearance (Fig. 6). Acute conditions are mainly due to pulmonary oedema or pneumonia, with pulmonary haemorrhage a distant third.

Fig. 6

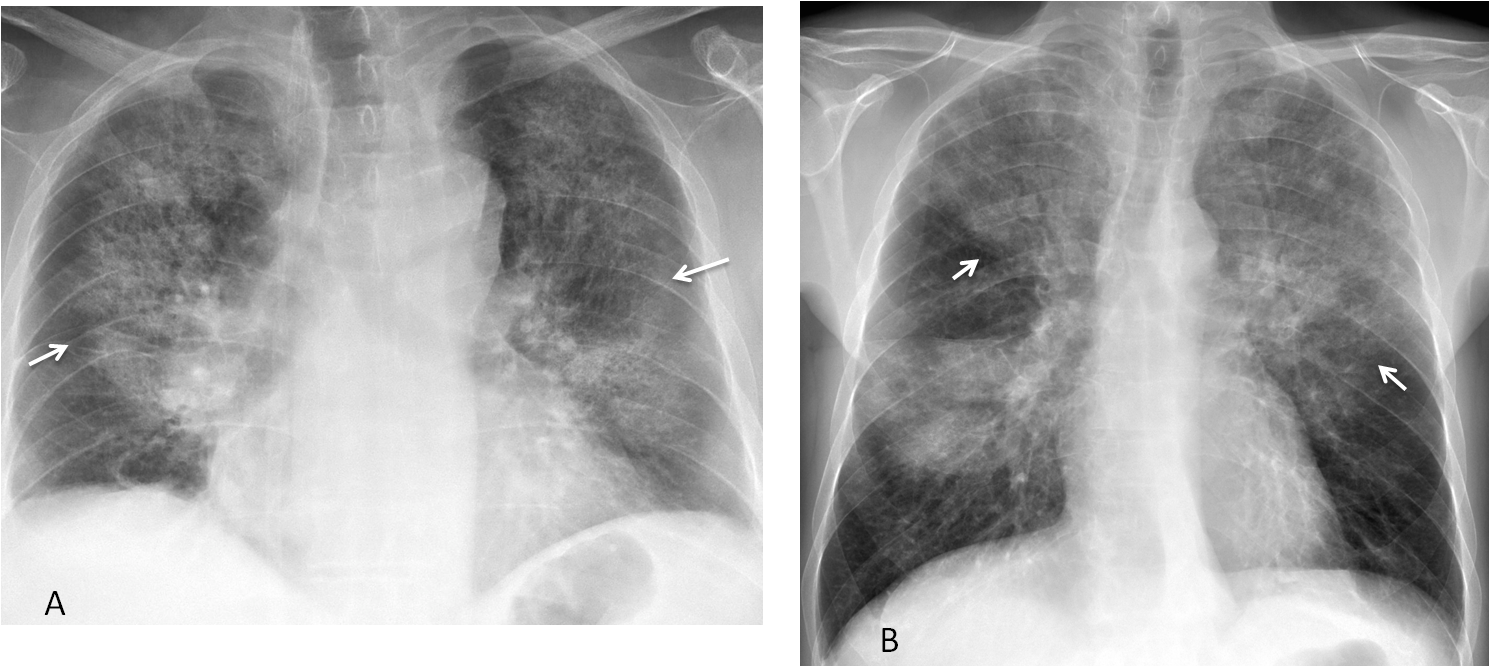

Fig. 6. Widespread air-space disease showing the typical butterfly pattern in a patient with pulmonary oedema (A, arrows). Widespread air-space disease (B, arrows) in another patient with fever. The extension of the infiltrates suggests viral pneumonia or immunosuppression. The patient tested HIV positive.

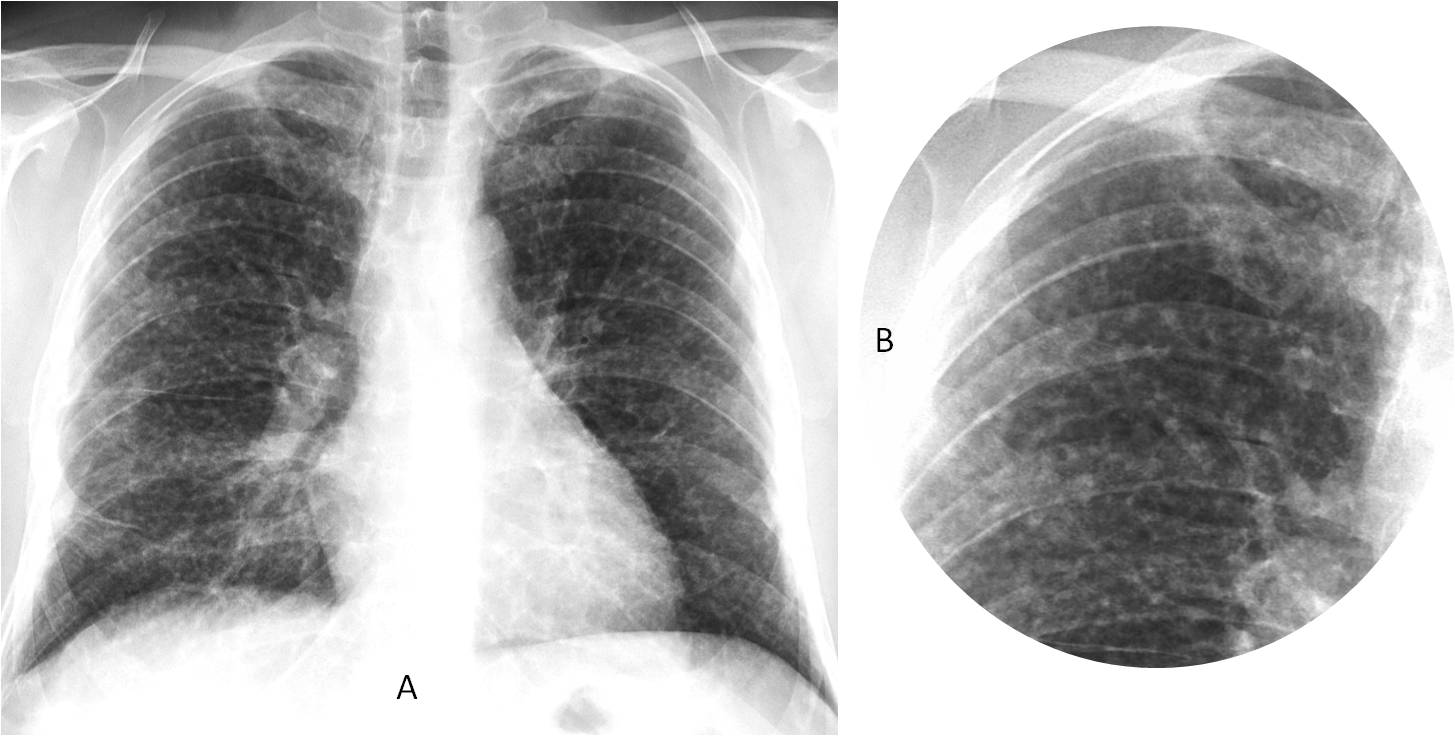

Chronic widespread air-space pattern can be due to chronic infection (TB), systemic disease, or adenocarcinoma (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7

Fig. 7. Two patients with chronic bilateral air-space pattern. The central location in the first one (A, arrows) is due to adenocarcinoma. The peripheral location in the second one (B, arrows) is highly suggestive of eosinophilic pneumonia (proven).

The nodular pattern consists of numerous nodules with a non-uniform distribution throughout both lungs (Fig. 8). Most commonly seen in metastatic disease.

Fig. 8

Fig. 8: 54-year-old woman with multiple nodules of varying size in both lungs (A and B, circles), secondary to metastases from breast carcinoma.

The miliary pattern consists of multiple discrete opacities (<3mm) distributed throughout both lungs. The most common cause of miliary nodules in acutely ill patients is an infectious disease. The first consideration should be miliary TB (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9

Fig. 9: 27-year-old HIV-positive woman with fever and malaise. Chest radiograph (A) show a widespread miliary pattern, better seen in the insert (B). Left hilum is enlarged (A, arrow). Associated lymphadenopathy is not uncommon in HIV patients. Diagnosis: Miliary TB

Among the chronic conditions manifesting as a miliary pattern, uncomplicated silicosis is the most common (Fig. 10). The diagnosis can be confirmed by eliciting a history of exposure. An alternative diagnosis is miliary metastasis (thyroid, renal cell carcinoma).

Fig. 10

Fig. 10: 55-year-old man with mild cough and a chronic miliary pattern (A and B). Interrogation confirmed a long history of dust exposure. Diagnosis: Uncomplicated silicosis.

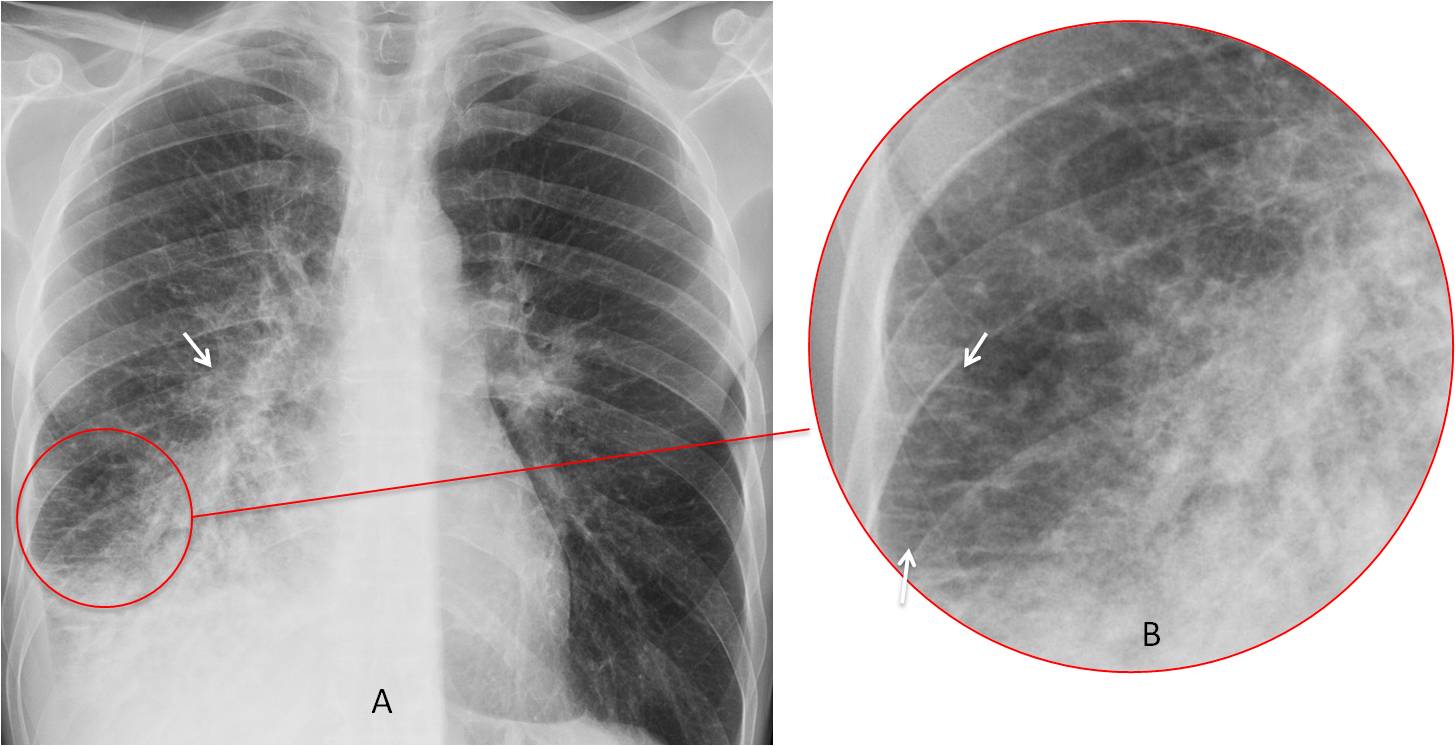

The septal (lymphangitic) pattern is characterised by the presence of Kerley A and B lines. When acute, the most common cause is interstitial pulmonary edema. When chronic, the main origin is metastatic spread of an abdominal neoplasm. A unilateral chronic septal pattern points to carcinoma of the lung (Fig. 11).

Fig. 11

Fig. 11: 45-year-old man with carcinoma of the right lung (A, arrow) and lymphangitic spread. Kerley B lines are better seen in the cone down view (B, arrows).

To summarise, pulmonary lesions produce several patterns that a competent radiologist should be familiar with. To facilitate the diagnosis, the patterns may be classified as localised or widespread. Both of these are subdivided into acute or chronic.

The most common and recognisable localised patterns are air-space pattern, lobar collapse, and solitary pulmonary nodule.

The most common and recognisable widespread patterns are air-space pattern, miliary, septal (lymphangitic) pattern, and multiple nodules.

I believe that other widespread patterns, such as reticular, reticulonodular and honeycombing are difficult to identify on chest radiography and should be investigated directly with CT.

Dr. Pepe’s teaching points:

1. Pulmonary lesions are classified by their patterns.

2. Pulmonary patterns are subclassified into localised or widespread (either acute or chronic).

3. Determining the location of the lesion may suggest the diagnosis in certain cases.

Reticulonodular pattern

Cardiac size is in the normality´s high limit.

There is a reticulo-nodular pattern predominantly on the inferior lobules, with a micronodular thickened of the cissures.

Any medical personal hystory of interest?

Carcinomatosis lymphangitis must be considerated.

Reticulonodular pattern. Probably due to lymphangitic carcinomatosis.

Reticulonodular pattern

Both lung volumes are preserved or mildly increased, along with the bilateral reticulonodular pattern in young female, LAM should be considered.

Reticulonodular pattern

Reticulonodular pattern in both lungs. Distribution is almost even in upper and lower part of the lungs. Mediastinum and both hilum are normalnie size. No pleural effusion. Young woman in child bearing age indicates on LAM. Langerhans histiocytosis less probable. Usually in heavy smokers, older and costophrenic angles are usually preserved. Limphangitis carcinomatosis should be always take into consideration.

K

– Septal pattern- Kerley lines- pulmonary interstitial edema

– Ill-defined pulmonary nodules in the lower lungs- haemosiderosis

– Thickened fissures- subpleural edema

– Double right heart border- enlarged left atrium

– Cephalization

– Right pleural effusion- posterior costo-phrenic angle

Congestive heart failure- Mitral stenosis

I’d like to ask if the patient have AIDS?

If yes, PCP should be considered

If not , I’m still with LAM.

No AIDS

….Stimatissimo professore…..il pattern x-grafico è quello micronodulare, prevalente alle basi….si associa a lieve quota di versamento pleurico e congestione vascolare….il soggetto è giovane , non fuma, non ha adenopatie ilo-mediastiniche, pertanto dovrebbero escludersi la TBC, la bronchiolite del fumatore, l’istiocitosi iniziale,le metastasi….potrebbe essere la forma subacuta di una alveolite allergica estrinseca(anamnesi anche lavorativa)….

Bilateral reticulo-nodular interstitial pattern, more towards bi-basal regions – Usual Interstitial pneumonia

Other DD: Lymphangitic carcinomatosis

Perhaps the predominant pattern is reticulo-nodular, but with alveolar filled disease in inferior lobules

Would like to make a short comment. In my opinion, patterns are meant to shorten the diagnostic options. In this case, recognizing Kerley lines limits the diagnosis to two main options: interstitial edema vs. lymphangitic carcinomatosis. The first option is the most likely one in an acutelly ill patient.

Congratulations to DrPedro, who made an accurate interpretation

Only part I of the interpretation… Gracias. 🙂